How Scary Are Ghost Stories in This Pandemic Year of Wildfires, Hurricanes, and Police Violence?

M. Dressler on What Gothic Novels and Speculative Literature Can Teach Us About Life Right Now

I write ghost stories for a living. I’ve loved haunted tales for . . . forever. The first one I remember reading, finding it by accident in the narrow, hugging aisles of my elementary school library, drawn in by the glowing blue mirror on its cover, whispered into my ear about the longings of lonely young girl who falls under the spell of another young girl—a dead evildoer hiding inside a beautiful glass reflecting ball in the garden of a Massachusetts estate. This was Jane-Emily, Patricia Clapp’s study of innocence and anger and what happens when the two are thrown together, tightly compressed.

In middle school, the gothic I read repeatedly was Henry James’ classic, The Turn of the Screw. My mother, an avid reader who loved giving me books that were always a bit ahead of my years, told me it was a kind of puzzle: were the dead lovers Miss Jessel and Peter Quint really watching malevolently from the rushes and hovering over the ramparts of that Essex summerhouse—or were they all a figment of an isolated governess’s wild imagination, her frustrated desires?

In supernatural literature, I soon learned, there were ghosts who were definitively ghosts; ghosts who might or might not be ghosts; and “ghosts” who weren’t anything of the sort—like the mad Mrs. Rochester of Jane Eyre or Daphne DuMaurier’s willful Rebecca—souls capable of expression beyond their prisons (and, although I didn’t understand this until much later, capable also of transmitting troubling ideas about gender, race, class, and power as sticky as any ectoplasm left on unlit bannister).

By the time I met Shirley Jackson, I wanted to become a novelist who wrote books that were both real and suggestive, ghostly, and more, “enthralling” yet challenging, with all the breathing, pounding, groaning weight of The Haunting of Hill House. Jackson, more than all the rest, made me want to write stories that were equal parts tense and revealing; that wound readers up for reason. Watch, Jackson seems to say through her haunted house, how people behave when everything they think they know about the world begins to shatter. Look at how many of them do not behave particularly well, and usually only in their own interest. Look how blind they are to what is right in front of them. Look how they can’t seem to find their way into the same room, at the same time. Look how cut off they are from one another. Look how they search for blame, for relief, even for comedy. Look how you think the hand that you are holding onto so tightly in the night isn’t the friend you thought it was.

When I began, after writing several works of fiction about the ghosts of history, to write my own series of literary gothic novels, hoping to add to that deep well of work that draws on the form of the ghost not as mere jump-scare but as a figure slicing through the world—from Toni Morrison’s magnificent Beloved to the recent, brilliant Cemetery Boys by trans author Aiden Thomas—I found myself listening, above all, to what dead characters have to say about surviving where you aren’t supposed to.

In supernatural literature, I soon learned, there were ghosts who were definitively ghosts; ghosts who might or might not be ghosts; and “ghosts” who weren’t anything of the sort.

This is what it’s like to live in the shadows. Look at who is who is allowed to express their anger and who isn’t. Want to spend some time thinking about who gets to be visible and who doesn’t? Who gets to patrol a border—between, say, life and death, between seen and unseen? Whose idea of “order” or “boundary” wins? Where should our fears really lie? And tell me, why do you living pull for the ghost hunter and not the ghost? Maybe there are good reasons to be disturbed, maybe you’re wrong to think there’s nothing under the comfortable bed, in the tidy closet, in the forgotten attic, in the Home Depot-furnished garden, in an empty schoolhouse where the children used to sit in front of their in-person teachers?

Gothic novels, and “speculative” literature in general, have much to teach us about borders, power, fear, anger, and our options for responding to all of them; for a writer in 2020, the disturbed, shifting soils of the moment are rich and strange with all of these, as well as salted with heartbreak, and stirring with hope. And although book sales, book tours, bookstores and book culture have been hit hard by the pandemic, by economic strain and struggle, and by the thefts of technology, it’s still safer (if not always financially so), still less frightening, these days, to be a writer than it is to be a nurse, a grocery store worker, a bus driver, a teacher. I’ve been spending 2020 sitting at a computer, working alone, remotely, normal for writers even before the pandemic . . . but awfully, abnormally out of touch-range, glimpsing people other than my immediate family only as distant, fleeting shapes, as the dead from COVID-19 pile high on graphs and in morgues, as Black Americans continue to be gunned down in their beds and gardens, as refugees languish at border fences and behind iron bars, living or dying far from what a life actually lived might be or have been.

I’ve found myself, this year, more than once simply stopping and refusing to write—telling myself I must simply shut up and be quiet and listen to others’ lives and deaths. I’ve questioned the role of my work at a moment, no, an ongoing history of deep danger for so many. I’ve watched my writing variously halt, sputter, insist, fail, resist, falter, and rise up again. I’ve been clinging like grim death to rebellious spirits, characters who try, as best they can, to take on the world, remembering as I write that every character in a novel is always a ghost, a phantom, present but not, dragging along a chain of words, asking: will you pay attention? I’ve had to reclaim writing as a form of attention to life and death, while at the same time gathering blankets and food and toiletries for some of the thousands (in the state where I sit writing this essay) who have been forced to evacuate their homes and towns, fleeing deadly, climate-change fueled fires. I’ve forced myself to look at maps and see not outlines, statistics and see not vague apparitions, embody the reality of human beings I cannot reach. And I have had to admit that my own house could burn or is already burning down, that what once seemed fantastical is real, that a thing starts as a problem or an anger or an injustice or an error or a cold calculation and eventually manifests, fully, completely, wherever it can.

Writers know that imagination is important but it isn’t everything. Imaginative action matters. A book can distract or insist, and sometimes both. The human body can turn pages. But which ones? And how? In some stories, the ghost raises a stripped finger, points, and says,

I’ve been telling you, for god’s sake.

Gothic novels, and “speculative” literature in general, have much to teach us about borders, power, fear, anger, and our options for responding to all of them.

When my series of gothic novels began to be published, I was surprised by something I shouldn’t have been: people started telling me about the spirits they’d encountered. Usually they came up to me with an incredible shyness. I’ve never told anyone this before. I’ve always been afraid of what will people will think of me. They assure me they live in a science-based, a fact-anchored world—I assure them I do, too—then tell me how their Puerto Rican grandmother banged the pots in the kitchen, night after night. How after a beloved husband died—he was a collector, he collected watches—his wife found every timepiece in the house cracked and broken. How a loved one came to say goodbye and she stood there, on the carpet, just as plain as you or me, how the light came on for no reason, how he grabbed my clothing from behind, and pulled on it, really gently.

Without exception, every one of these stories told to me was either about love, or anger, or both. Asked for the first time at a bookstore reading (back when authors could do these) whether or not, since I wrote about ghosts, I actually believed in them, I wanted to be honest, so had a carefully developed answer:

I don’t believe ghosts are real, but I do believe that we see or feel them. Ghosts are what we hold here with us in the space of reality for a moment, by accident or by will, and are then deeply startled, shocked, by the experience. We’re shocked, I think, not because we are afraid or unafraid, surprised or unsurprised, but because we discover, all at once, and despite all our protestations to the contrary, that we are a member of a not fully empathetic species, because we are more selfish than we know or care to admit, and more bordered than we realize.

It seems to me the sudden experience, that sudden specter of an Other outside of us, that stunned awareness and acceptance of a freestanding soul that for some reason wasn’t really possible to see while that person was alive, for a moment holds all our attention so powerfully, so unexpectedly, that we ourselves disappear—an experience that itself is so unsettling we sometimes need to turn it into stories, books, or films in which the ghosts are bad, bad, bad, or at least uncomfortable, and so must be put down before we finish our popcorn, sitting in this reclining seat, this safe, upholstered space, always safe, always available to us, because the movie theaters will always be open, right?

Writers know that imagination is important but it isn’t everything. Imaginative action matters.

It was, is, as close as I can come to talking about something I really don’t like to talk about: that I think this way about ghosts because I know for a fact I didn’t believe my father was real until he died. I only understand, now, that I didn’t see him as whole until he was gone. While he was alive, I saw him more as a character, a rendering of a human being, father, in my head, than as an entity completely apart from me and from my needs. Until the light came on. Until I saw my name scribbled in a handwriting that wasn’t mine. Until something caught my shirt, not at all gently, while I was sitting at his desk, writing his eulogy.

It is, as you might guess, frightening to write ghost stories. You have to look in certain, dark corners. It’s frightening me to finish my next novel, honestly, and to write at all at this moment, but I tell myself my job is to pay attention, stay awake, and if I can to try to keep a reader up, too. For the record, I have never thought scaring readers, or any human being, simply for the sake of scaring them was anything worth aspiring to. There are too many things worth being afraid of, and things worth seeing fully and admitting, as well as ways to know when your fear is being used against you, and others, and know when what is truly disturbing, horrifying, isn’t the whole beings of all those who have needlessly died this year but who among us it was who sat back, watched, reclined in a seat and thought, all too easily, Yeah, those others, trust me, they aren’t real, those numbers, they don’t count, they don’t add up, they aren’t even there.

The ghosts of 2020 say otherwise.

__________________________________

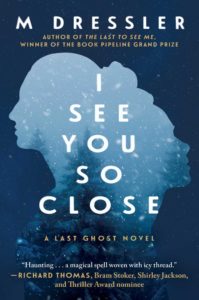

I See You So Close, Volume 2: The Last Ghost Series, Book Two by M Dressler is available via Arcade Publishing.

M Dressler

M Dressler is the author of The Last Ghost trilogy. She lives and writes on the Oregon coast and in southern Utah. Read more about her work at mdressler.com.