How Sam Shepard Became the Star Playwright of New York’s Counterculture

Robert M. Dowling on the Early Years of a Genius of Avant-Garde American Drama

Charles Mingus marveled at his roommate’s self-assurance as a writer. “He could walk into a room with a typewriter and not leave until he finished a play,” he said. “No revisions, just typing.” Shepard would complete fifteen plays in just five years on this typewriter, and he maintained his devotion to the dependable tool, which he likened to an old Chevy, until the end of his life. “You’re seeing a phenomenon,” he said later of watching the hammers thwack ink onto the page. “You’re seeing this apparition taking place. I don’t mean to sound hocus pocus about it, but there’s something taking place, and you’re true to that.”

That summer, 1964, Shepard was writing quickly and hustling on the Off-Broadway theater circuit. Somehow he acquired Edward Albee’s phone number, mustered his courage, and dialed. Albee was thirty-six but already a kingmaker of the theater scene after the successes of The Zoo Story and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. In Albee’s sonorous patrician accent (“Awl-bee,” he would correct people), the dramatist invited Shepard over to discuss a new script at his duplex in the West Village. Mingus agreed to join him for moral support, but when Albee, whether through nonchalance or lechery, answered the door wearing nothing but a beltless bathrobe, Mingus balked and hightailed it out of there.

Shepard went inside, handed Albee his latest play, a one-act about the Vietnam draft titled Up to Thursday, then raced off after Mingus.

Shepard would astonishingly make his mark as an avant-garde playwright on the downtown scene with only a few months of networking and no production to his name. Other hopeful young playwrights such as Lanford Wilson, LeRoi Jones, Megan Terry, John Guare, María Irene Fornés, and Terrence McNally were also cutting their teeth at the makeshift drama venues in the churches, restaurants, and cafés that populated Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side, all of which were within easy walking distance of Shepard’s Avenue C apartment.

At this time, total production cost at any of these “theaters” was usually less than forty dollars. Most of the productions were free and open to the public, though hats were often passed around and coffee was sold. The four most notable Off-Off-Broadway houses were Theater Genesis, La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, Judson Poets’ Theatre, and Caffe Cino, and Shepard would stage his freeform one-act plays in every one of them. “New York was like that in the Sixties,” he said later. “You could write a one-act play and start doing it the next day. Nothing like that exists now.”

Shepard would astonishingly make his mark as an avant-garde playwright on the downtown scene with only a few months of networking and no production to his name.

Edward Albee, along with the producers of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder, had started a theater workshop for experimental new playwrights called the Playwrights Unit, which would finance an annual series called Theatre 1964. (This changed year to year; Shepard would appear in Theatre 1965.) In early August, before rehearsals at Theater Genesis for Shepard’s world premiere as a playwright, Albee agreed to produce Shepard’s work. “I’ll be able to write anything I want to,” Shepard crowed to his mother, “no restrictions on content or form.” La MaMa ETC would soon join the Playwrights Unit and put on one or two more after Theater Genesis’s double bill, which was scheduled for October. Despite the warm welcome by other Off-Off-Broadway theaters, Shepard recalled, in the downtown theater scene, “Theater Genesis became my home.”

The second play that Cook had asked Shepard to add to the evening, Cowboys, “was about me and Charlie [Mingus] on the streets of New York,” Shepard told a reporter, “because that’s what we used to do in Duarte, play cowboys in the street, and when we got to New York we just kept doing it.” “It seemed bizarre to me,” he elaborated on his play’s theme of dislocation, “this sense of being from a desert region, then suddenly being surrounded by immigrants, pigeons, and jazz musicians.”

And so he wrote the twenty-one-page script consisting of two friends, Stu (Shepard) and Chet (Mingus), who are frightened of the city and find themselves on the street playing Cowboys and Indians. A fellow Village Gate waiter and Theater Genesis actor named Kevin O’Connor glanced over Cowboys and The Rock Garden, and at first blush thought they were “garbage.” Later, he realized that “you can’t tell with Sam’s plays when you read them. You only know when you experience them. And when I did that, I realized that we were into gold.”

The cast started rehearsals within a week of Shepard’s submission of Cowboys, and there was no budget. “I can remember getting props off the street,” Shepard recalled. “We’d take Yuban coffee cans, punch a hole in them, and use them for lights. We did it all from scratch.” “But it was exciting,” the Genesis member Georgia Hadler reminisced. They didn’t care about not having money for a bigger stage or props or much else. They didn’t care about Broadway, and they didn’t care that Broadway didn’t care about them. They especially didn’t care, Hadler emphasized, what outsiders thought when they came to see a show: “You could take acid and sit in the audience, and nobody’s gonna be mad at you,” she said. “Or you could shoot up [heroin] in the kitchen if you had to, and some people did. Not everyone was brilliant, but we felt brilliant.”

*

That summer, Shepard was seated on the stoop of a notorious drug dealer’s apartment building at Tenth Street and Avenue C when a man climbing the steps noticed him scribbling in a notebook. This was Peter Orlovsky, a Beat poet and romantic partner of Allen Ginsberg. When Shepard told him he was writing a play, Orlovsky helpfully responded, “You know, there’s a woman around the corner on Second Avenue….Why don’t you take it over there and see if she’d want to do it?” So Shepard hopped off the stoop and over to Second Avenue and Ellen “Mama” Stewart’s La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. “And, there,” he said, “was Ellen in all her glory. She usually wore really tight pants and kind of ballerina slippers and a glittery green thing. She was very sexy, you know.” Shepard asked her straight up, “Would you be interested in this play?” With barely a glance at the script (either Dog or The Rocking Chair), Stewart gustily replied, “We’re gonna do it baby!”

Stewart also hired Shepard as a part-time waiter at La MaMa ETC. Located in a loft above a florist at 82 Second Avenue, at Fifth Street, the performance space was a short walk from where Cowboys was soon to be performed. Stewart, La MaMa’s founder and namesake, was a transplant from New Orleans who supported her theater designing bathing suits. La MaMa wouldn’t make its name as a nerve center of avant-garde ingenuity until a few years later, when Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical staged its world premiere there in 1967, and by association La MaMa became a countercultural phenomenon.

Tom O’Horgan, who would direct Hair, had his directorial debut at La MaMa with a production of Jean Genet’s The Maids during the same month Shepard enjoyed his world premiere as a playwright. Shepard was serving hot chocolate during one of these showings of The Maids when police and firemen came into the café in hopes of finding some excuse to shut Stewart’s shows down for obscenity. Genet’s play was acted by three men in drag playing women’s roles, a weird spectacle for the authorities who arrived midshow. “It was really a scene,” Shepard said,“and the firemen shut it all down, and then [Stewart] would start it up again.” The theater venue was permanently shuttered that month, but Stewart just found a bigger space nearby.

*

Cowboys and The Rock Garden opened at St. Mark’s on October 10, 1964, for a three-weekend run. For Cowboys, the stage was strewn with sand and gravel; two sawhorses were set up with blinking lights; and a recording made by Shepard and Mingus while driving around New Jersey with a tape recorder provided ambient street sounds for the show. For Shepard, when the actors began to read his lines, the effect was transcendent: “It was quite amazing to me to recognize that putting on a play was an entirely different process from writing one,” Shepard mused.

“It was quite a shock to see actors take hold of what I’d written, and I suddenly realized what theater was all about…that it was this live thing that took place between the actors and the audience.” The New York World-Telegram and The Sun printed an ominous word of caution to fainthearted theatergoers in their “Religious News”: “Rough language will be ringing through the historic air of Manhattan’s second oldest church building.” But the article featured a conciliatory comment by the minister of St. Mark’s, the Reverend Michael Allen, a tireless activist and advocate for the arts. “I’m not sure I approve of everything that will be said here,” Allen told the reporter, but “how can a church minister to people unless it’s willing to listen to them?…Our job is to help everyone in the parish. If there is a minority group, our job is to help its members be dignified, equal, respected citizens. If there are playwrights, it is to help them be playwrights.” “What about the gospel?” the reporter asked. “I think,” Allen replied, “that is the gospel.” (Shepard and Mingus, as if to accentuate his point, painted fuck god in large black letters on a wall inside the church.)

Shepard had written to Jane Rogers in early August that The Rock Garden “really cancels out everything that I’ve written so far. I wrote it in four days and it was like piling everything into one suitcase.” In fact, it was special to him well after he’d made it big. The Rock Garden, he said in 1991, “was sort of the beginning of something that reverberated from there, which I didn’t realize at the time.”

The Rock Garden is an absurdist reflection on the ennui of growing up in a middle-class California home. Based on Shepard’s relationship with his parents, The Rock Garden is a slapstick play that’s performed deadpan. In the first scene, Shepard’s character, Boy, is seated in a rocking chair wearing only his underwear, while his mother, Woman, is lying on a bed swaddled in blankets. The two perform a vaudevillian costume routine wherein Woman says that Boy’s legs resemble her father’s, and the teen, privately disgusted by his genetic heritage, exits and returns in pants; then it’s his feet with shoes, then his torso with a shirt. In the second scene, father and son are discovered seated naked aside from their underpants.

The father, Man, prattles on about mowing the lawn, painting the fence, and managing their orchard’s irrigation, while the son periodically falls off his chair from boredom. When it’s the teen’s turn to reveal his own inner thoughts, he does so with an aria about sex: “When I come it’s like a river. It’s all over the bed and the sheets and everything. You know?” Boy delights over how to give a woman an orgasm and ends the play with the lines “I really like to come almost out and then go all the way into the womb. You know, very slowly. Just come down to the end and all the way back in and hold it. You know what I mean?” The father, in a state of shock, tumbles to the floor.

Shepard’s graphic sex talk showcased the group’s “conspicuous heterosexuality,” as Ralph Cook phrased it, which distinguished them from the more gender-bending fare less abashed theatergoers might find at La MaMa or Caffe Cino. A friend of the stage manager’s said Theater Genesis “did have a bit of a Boys’ Club.” “They didn’t hate women, but they didn’t appreciate women,” agreed one of the group’s female volunteers. “They all held women at a distance.” And, of course, Cook’s regular playwrights around this time—Shepard, Murray Mednick, Tony Barsha, Walter Hadler, Leonard Melfi, and Tom Sankey—were all men. Barsha referred to their communal “Macho Americano” attitude as the “Hells Angels of the Off-Off-Broadway scene. A lot of pot, and a lot of women, and a lot of messing around in that area, so Genesis definitely had that reputation, and rightly so.”

The maverick from California would be heralded by the country’s most esteemed news source, the New York Times, as downtown’s “generally acknowledged ‘genius.’”

But the collective sensibility of Theater Genesis, male or female, was that of all people involved in theater during the downtown underground scene: in equal measure tough, funny, cynical, talented, disgruntled, and steeped in the adventure of a lifetime. “Theater Genesis is a mix of counterculture ingredients,” Newsweek’s drama critic Jack Kroll summed up their overall reputation Off-Off-Broadway, “a coolness that can explode like liquid oxygen, a dropout hipsterism, a polymorphous perversity of language and feeling, a Zap Comix mocking of straight heads.”

The final monologue in The Rock Garden was more pornographic than even some avant-garde audiences could endure. And yet one night, Lee Kissman (who played Boy) recalled, laughing at the memory, “I looked up from my perch out toward the audience and three nuns were sitting in the first row immediately in front of me. They seemed to be enjoying themselves; they didn’t flinch.” Still, Shepard’s steamy theatrics and graphic dialogue did little to excite the critics. “All these guys said it was a bunch of shit,” Shepard said, that he had “imitated Beckett or something like that.”

The most rancorous pan came from Jerry Tallmer’s review in the New York Post, which reviewed only Cowboys, not The Rock Garden, and condemned Shepard as the latest proselyte of what he called Edward Albee’s emergent “Theater of Assault.” “In the Theater of Assault,” Tallmer wrote, “the object is not so much to shock or awaken an audience as to attack it, directly, personally, unilaterally.” Shepard’s “psychic spleen” was in the tradition of Albee’s The Zoo Story and Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and not in a complimentary way. “Mr. Shepard is angry at (a) everybody who must watch his play, (b) everybody in crowded, ugly New York City, and (c) everybody.” Ralph Cook was apoplectic over the review. Tallmer had seen the second performance, before the production had settled into its own.

And for two long weeks, Tallmer’s was the dominant review. But later in the run another notice appeared, one that would single-handedly launch Shepard’s career, written by Michael Smith, a playwright himself, who thought Tallmer was a “second-string critic.” While seated on a bench in Washington Square Park, Shepard read and reread the rave Village Voice review in stunned silence. In it, Smith argued that Shepard’s plays defied categorization, and he warned other drama critics not to bother trying. “Shepard is feeling his way,” he said, “working with an intuitive approach to language and dramatic structure and moving into an area…where character transcends psychology, fantasy breaks down literalism, and the patterns of ordinariness have their own lives.”

And Smith was certain that these two short plays portended a great future for the twenty-year-old in the dramatic arts. “One comes away feeling that the playwright has kept some of his secrets, perhaps kept them from himself,” Smith wrote, “but at least he has secrets to keep.” Only a couple of years later, when Shepard was the poster child for the new underground theater, Michael Smith said that “I felt forever after as though I’d ‘discovered’ Sam Shepard.” And by critical standards, he had. More accolades poured in. The future director and dramaturg Bill Hart, who would later room with Shepard, direct several of his plays, and serve as best man at his wedding, exited the church euphoric: “He had literally altered my consciousness.” Lee Kissman drank often with Hart, and after the performance, they walked with Smith back to his apartment in the West Village, where, Kissman remembered, “they both were blown away. Neither of them could stop talking.”

Another promising young playwright named Murray Mednick was also in the audience. Shepard had already seen a play of Mednick’s and knew he had to meet him. Mednick and Shepard started playing pool regularly at the Blue & Gold Tavern, a popular East Village dive a couple of blocks from St. Mark’s. Shepard was captivated by Mednick’s “tough guy” walk and streetwise Brooklyn speech and mannerisms. “He never knew anybody like me,” Mednick said, “a real Jewish intellectual. A real New Yorker.” Mednick was equally captivated by Shepard’s blend of homegrown Americana and bookishness. “Sam read a lot. And that’s what our friendship was mostly about—stuff that we read.” But being friends with Shepard “wasn’t so easy,” he said.

He beat you at everything—pool, he could ride horses. He was a good athlete. And he was good-looking. So if you go into a room, all the women were looking at him. Talented and intelligent, he had it all going. It was just amazing that he had all these good things, and then, all of a sudden, he got famous.

This last came as a shock. “We were all just kids really,” Mednick said. If not for Smith’s bellwether notice in the Village Voice, and that paper’s hungry downtown audience, Shepard might well have initiated his fallback plan to return to college and live a quiet life as a veterinarian in the San Gabriel Valley. Instead, only a year later, the maverick from California would be heralded by the country’s most esteemed news source, the New York Times, as downtown’s “generally acknowledged ‘genius.’”

“From the earliest day,” Bill Hart agreed, “everybody thought of Shepard as the best—right away.”

__________________________________

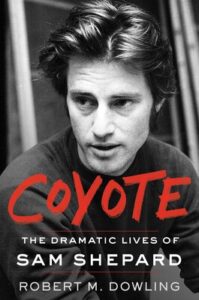

Excerpted from Coyote: The Dramatic Lives of Sam Shepard by Robert M. Dowling. Copyright © 2025 by Robert M. Dowling. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Robert M. Dowling

Robert M. Dowling is professor of English at Central Connecticut State University. He is the author of Slumming in New York: From the Waterfront to Mythic Harlem and the biography Eugene O’Neill: A Life in Four Acts, which was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist for biography in 2015. He has also coedited the 2021 compendium of interviews Conversations with Sam Shepard. As an authority on American drama, he has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Boston Globe, among other media venues. He serves on the editorial board of The Eugene O’Neill Review and is an elected Board member of the Eugene O’Neill Society (President of the Society, 2018–2021).