How Queen Elizabeth I Remembered and Honored Her Mother, Anne Boleyn

Tracy Borman on Two of British History’s Most Famous Monarchs

May 19, 1536. Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s scandalous second wife, stands on a scaffold at the Tower of London and prepares to meet her death. She delivers an eloquent, dignified speech, with a final plea: “If any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best.” More than anyone else she was leaving behind, it was her daughter whom she wished to think well of her—and, perhaps, to rehabilitate her reputation. She could not have predicted with what vigor and commitment the future Elizabeth I would dedicate herself to the task.

*

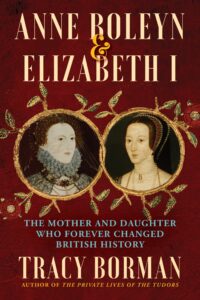

Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I. Two of the most famous women in British history. Their stories are as familiar as they are compelling. Henry VIII’s obsessive love for Anne turning to bitter disappointment when she failed to give him a son, her bloody death on the scaffold barely three years after being crowned queen. Her daughter Elizabeth’s turbulent path to the throne, her long and glorious reign—a “Golden Age” for England, with overseas adventurers, Shakespeare and Spenser, royal favorites, the vanquishing of the Armada, all presided over by the self-styled Virgin Queen.

And yet, until now, Anne and Elizabeth’s stories have never been told together: the nature of their relationship, the impact it had on their own lives and those around them, and its enduring legacy. In part, this is understandable. Elizabeth was less than three years old when the Calais swordsman severed her mother’s head at the Tower of London on May 19, 1536.

Even while Anne had lived, Elizabeth had seen little of her and had followed the traditional upbringing for a royal infant, established in a separate household, far removed from her parents at court. And then there is the impression that Elizabeth herself gave. “She prides herself on her father and glories in him,” observed Giovanni Michiel, the Venetian ambassador to England during the reign of Elizabeth’s sister Mary. The many references that Elizabeth made to her “dearest father,” and the way in which she tried to emulate his style of monarchy when she became queen, all support this view.

By contrast, Elizabeth is commonly (but inaccurately) said to have referred directly to Anne only twice throughout her long life. She made no attempt to overturn the annulment of her mother’s marriage or to have her reburied in more fitting surrounds than the Tower of London chapel. The obvious conclusion is that Elizabeth was at best indifferent towards, and at worst ashamed of Anne. But the truth is both more complex and more fascinating. Exploring Elizabeth’s actions both before and after she became queen reveals so much more than her words.

To the very end, her daughter had honored Anne’s scaffold plea to “meddle” in her cause.One of the most revealing pieces of evidence about Elizabeth’s feelings towards her late mother can be found in her personal possessions. We have a detailed record of these, thanks to the inventories that were taken of these during her long reign—and one that was drawn up after the death of her father, Henry VIII, in 1547. This includes a list of the late king’s possessions which his daughters were given for their own households. As the elder, more favored princess, Mary was at liberty to select an array of rich furnishings from among her father’s vast treasure.

*

The Tapestries

Elizabeth’s choice from her late father’s possessions was more frugal and mostly confined to religious items, reflecting her intense piety. But it also included something that was closely connected with Anne Boleyn: a set of tapestries depicting Christine de Pizan’s The City of Ladies. Anne had encountered the work during her youth in the courts of the Netherlands and France, and an English translation had been published in 1521.

The ideas it put forward about female education and leadership were a source of profound inspiration for Elizabeth. The inventory reveals that the six large tapestries were “delivered to the Lady Elizabeth… towards the furniture of her house.” Each measured an average of eight by five meters, so if hung together they would have required a room or hall with a perimeter of almost fifty meters. To have such a prominent visual reminder of Christine de Pizan’s work hanging on the walls of her home was a clear demonstration of how much it had influenced Elizabeth—and of how greatly she revered her mother’s memory.

The Ring

One of the oldest and most precious items in the collection of Chequers House, the British prime minister’s country residence, is a tiny, exquisitely crafted ring, fashioned from mother-of-pearl and embossed with rubies and diamonds. It opens to reveal two portraits: one is of Elizabeth I; the other is thought to be of her mother, Anne Boleyn, the most famous—and controversial—of Henry VIII’s six wives.

When closed, the two portraits almost touch: face to face, mother to daughter. The Virgin Queen was well known for her love of expensive and elaborate jewelry, yet this comparatively simple piece was her most cherished possession and she kept it with her until the day she died. It is a poignant symbol of the private reverence in which she held her late mother throughout her long life.

The “Bed of Estate”

Among the largest items that Elizabeth inherited from her mother was “the rich Bed of Estate” that Anne gave birth to her in. Described as “one of the richest and most triumphant beds,” it was said to have formed part of the ransom of the Duke of Alençon, who had been captured at Verneuil in 1424—possibly a nod to Anne’s time at the French court in her youth. Elizabeth later showed the bed off to one of her suitors, the Duke of Anjou and Alençon, and quipped that he might recognize it.

The Book of Hours

Elizabeth inherited a large number of books from her mother. The oldest is an exquisitely illuminated Book of Hours from the mid-fifteenth century. She inscribed it: “Le temps viendra / je Anne Boleyn” (‘The time will come / I Anne Boleyn’). Between the words “je” and “Anne,” she inserted a small drawing of an armillary sphere, which both she and her daughter used as their emblem.

The Gold Cup

A beautiful silver-gilt cup with the Boleyn falcon sitting proudly on top was made for Anne in 1535. After her death it passed to her daughter, who later gifted it to her physician, Richard Master, who had served her from the beginning of her reign. In 1563, he gave it to St John the Baptist Parish Church in Cirencester, where it is still on display.

The Falcon

The falcon was Anne’s most famous emblem and Elizabeth used it to decorate many of her palaces and possessions. Although most of the falcons made during Anne’s lifetime were destroyed by Henry VIII, one of them recently turned up at auction. Carved from oak and beautifully gilded, the crowned falcon rests on a bed of Tudor roses. It was one of 150 commissioned by Henry to decorate Hampton Court and is a rare survivor of Anne’s queenship.

Elizabeth died surrounded by her Boleyn relatives and the Boleyn coat of arms was proudly displayed throughout her funeral procession. Anne’s falcon badge was added to her daughter’s magnificent tomb in Westminster Abbey. To the very end, her daughter had honored Anne’s scaffold plea to “meddle” in her cause—and, as always, had “judged the best.”

____________________________

Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I: The Mother and Daughter Who Forever Changed British History by Tracy Borman. is available now from Atlantic Monthly Press.