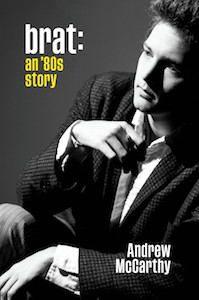

How Pretty in Pink Star Andrew McCarthy Became an (Unlikely) Teen Heartthrob

The 80s Brat Pack Member on the Iconic Role that Changed His Career

Since discovering it in high school, I hadn’t considered an option for me other than acting. And since holding my own during St. Elmo’s Fire, I felt on more solid ground in my choice of career, at least momentarily. That didn’t mean I was relieved of the constant anxiety that I would never work again. Exactly when and where my next job might come from was still very much in doubt. A teenage redhead I didn’t know at all would see to that problem and facilitate my getting the part that I’m still reminded of on a near-daily basis.

The Breakfast Club had recently been released, and with its success coming on the heels of Sixteen Candles, both John and Molly Ringwald were in an enviable position. A new type of teen film was emerging and John was the visionary behind it, with Molly as his muse. John’s movies had a singular voice, confidence, and sincerity. Molly was equally assured, unique and raw.

Pretty in Pink was to be their next collaboration. John had written the movie for Molly but he was going to only produce the film, handing the directing chore over to a soft-hearted, self-deprecating New York neurotic named Howard Deutch. All I cared about at this point was that they were coming to New York and, according to my agent, weren’t interested in auditioning me. They were looking for a “hunk,” a “star quarterback type,” to play the rich love interest to Molly’s girl from the wrong side of the tracks. I was informed I did not fit the bill.

But with St. Elmo’s Fire coming out soon, there was a bit of prerelease buzz. In some conversations—primarily the ones initiated by movie publicists—it was being called “the young Big Chill,” an ensemble film filled with stars a decade older, stars like William Hurt and Kevin Kline. (In fact, when St. Elmo’s Fire was released a few months later, one reviewer called it “a poor man’s Big Chill, a day late and a dollar short.” At least the publicists had done their job and gotten the two films spoken of in the same sentence.) And because of that chatter about my soon-to-be-released movie (you are never more intriguing than before anyone has seen your work), I was awarded a courtesy audition.

I waited my turn out in the hall. Most of the time actors go into an audition room and read the scene with a casting assistant—usually a well-meaning person and a terrible actor. But in this case Molly was there, seated beside the video camera. At the time, I had not seen any of Molly’s films, although it would have been impossible not to recognize her after walking past my newsstand on Sheridan Square and seeing all the magazine covers with her likeness.

Behind her, leaning forward, elbows on his knees, perched an eager, dark-haired, and well-intentioned man: the director, Howie. Then in the back of the room, behind the equipment, hands stuffed deep into the pockets of his baggy trousers as he tilted his chair back up on two legs, bobbing against the wall, was a blond-haired, soft-featured man with wire glasses: Hughes. He nodded in my general direction and never spoke.

I did my bit. Molly was attentive and read with care. No one else showed much interest.

“Thanks for coming in,” the casting associate muttered.

“Fuck ’em,” I thought on the way out.

Once the door was shut, Molly apparently turned to John and said, “That’s the kind of guy I would fall for.”

“THAT wimpy guy?” John said.

“He’s sensitive, poetic,” Molly said.

John wasn’t convinced, but over the next few days the calls to my agent went from “He did a nice job” to “We like him a lot for this.” It was testament to John’s belief in Molly that he got behind the idea and cast me. It was another example of what I believe was the key to John’s success in his youth films. Not only on-screen did John give young people credit for being full human beings with opinions worth listening to; he carried this line of thinking through in all areas.

Later, on set, John brought a small boom box around and between setups would play snatches of music and ask for the actors’ opinions. He was gathering information for what would become the soundtrack, and he wisely solicited the ears of the generation who would be listening. That soundtrack was as responsible for the success of the film as what appeared on the screen.

As I was offered the job only a short time before filming, and since there was no question of whether or not I would do the film, I returned to my old schoolboy ways and felt no need to read the script—until I was on the plane out to Los Angeles to begin shooting. The basic plot of the film—which John boasted he wrote in a weekend—hung on Molly’s character, named Andie, wanting to go to her school prom with my character, Blane.

In the end, peer pressure proves too much for Blane and he stands Andie up on the big night. Blane mopes at home and Andie takes comfort in her best friend; lesson learned. In the few scenes I had read of the script, it never occurred to me that Blane would lack moral conviction and back out. Reading on the plane, I was shocked by his spineless nature.

I felt my success rested on not being easily dismissed as some kind of interchangeable Hughes teen.

Upon landing, I called my manager, Mary, and complained, “This guy is a total loser. I can’t do this movie!”

“Honey, you read the script,” Mary replied. “You knew what happened.”

What could I say?

The cast had already been gathering for several days of informal rehearsals at the director Howie’s home when I joined. Whereas during rehearsals for St. Elmo’s Fire there had been an undercurrent of tension and competition, here things were loose, familial.

“Can we read the scene again?” I’d ask.

John, who would take a very active role during filming despite his producer credit, would shrug.

“We can if you want. We don’t need to.”

He was free and easy with changing dialogue as he heard us read, customizing it to who we were. At the end of my first day John said, “Things took a big leap today,” in an offhanded way. My presence was the only thing different about rehearsal from the days before, and I silently took his comment as a vote of confidence. This indirect, almost absent fashion marked the way John would speak with me going forward. But it was enough to dispel any doubts that I might have been miscast or was there against John’s instincts.

As a thank-you to Molly for getting me the part, I purchased her a large—about five feet tall—green Gumby doll, the Claymation character. Why this was how I chose to express my gratitude, I have no idea. Perhaps because it allowed me to present Molly with a card on which I had cleverly inscribed, “Gumby for you!”

Yet, as the shooting wore on—and although we are forever linked in a cinematic romance—Molly and I never grew close. I found her to be fiercely intelligent and determined. She was the epicenter of the Hughes world; no one knew it better or worked harder to maintain its integrity. Within a cast of equals, Molly was more equal, and her opinions carried added heft. So in a move that was more unconscious than deliberate, I concluded that to forge my own unique imprint—I felt my success rested on not being easily dismissed as some kind of interchangeable Hughes teen—my power on the set would come from maintaining some form of distance.

That I was older than Molly—at 22, I was starting to spend many of my evenings drinking in bars and clubs, while Molly was still in high school—was less responsible for the emotional gap that grew between us than this aloof position I adopted. Add to this, St. Elmo’s Fire came out early in our shoot and my reception in it had been warm and positive.

Overnight, I was a young actor on the rise. I began to be seen—and to feel—on more equal footing with the others. I started to take my space with more confidence. While my remote posture did nothing to foster a bond with Molly, the friction it created often sparked between us—and it could be argued that this tension added to an on-screen chemistry that palpably charged our scenes. But it can’t be overstated that without Molly’s support I never would have been cast in Pretty in Pink, and my career, and indeed my life, would have looked very different.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Brat: An ’80s Story. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Andrew McCarthy. All rights reserved.

Andrew McCarthy

Since starring in the movies he recounts throughout Brat, Andrew McCarthy has become a director, an award-winning travel writer, and a bestselling author. He has directed more than eighty hours of television, including Orange is the New Black, The Blacklist, Gossip Girl, and many others. For a dozen years he served as editor at large at National Geographic Traveler, and his award-winning travel writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, TIME, and elsewhere. He is the author of a travel memoir, The Longest Way Home, and a young-adult novel, Just Fly Away—both New York Times bestsellers.