How President Obama Marked 50 Years of Civil Rights Struggle With One of His Most Memorable Speeches

Cody Keenan on Putting Words Into the President’s Mouth

It was supposed to snow two days before the speech. I stumbled out of bed and pulled aside the window shade, hoping the city would be covered in a fresh blanket of white.

Nothing. Damn it. I let the shade fall closed and grabbed my phone, swiping for that one email that would define the day, wondering how many other people across the city were doing the same—how many working parents were praying schools would stay open, how many young staffers were hoping offices would close.

I was in a strange hybrid position: I wanted to get the day off and to go to work.

I got my wish: The federal government had declared March 5, 2015, a “snow day.” Not for a dome of polar chill that often pierced my lungs growing up in Chicago, not for the three-footers of heavy stuff I trudged through to grad school in Cambridge, not for the squalls of ice particles that sandblasted my face while canvassing for votes in Iowa. Just a solid four to seven late-winter inches on the way. Just enough for snow-phobic authorities to preemptively keep a couple hundred thousand employees off the District of Columbia’s roads.

If your self-importance swells while ascending the White House driveway for a meeting with the president, the Oval Office punctures it right away.

It offered the opening I was hoping for: unfettered access to the president of the United States.

I showered, dressed, and followed a lumbering salt truck down a quiet 14th Street to my office for the past six years: the White House.

*

Barack Obama stepped from the Colonnade into the West Wing, dusting a few of the day’s first flakes from his single-breasted, two-button charcoal suit crafted by his favorite Chicago tailor. His white shirt bore vertical gray stripes; his tie was a British regimental pattern—stripes running from left shoulder to right waist—in alternating shades of black, white, and gray. All were neatly pressed. He gripped a white foam cup embossed with a gold presidential seal. He’d worn no overcoat for the short commute from the Residence; to walk the length of the Rose Garden took about fifteen seconds. More snowflakes snuck in past him, a few spoiling his freshly polished Johnston & Murphys, black with a modern toe. He’d shaved within the hour.

“Can you believe this shit?” His expression mirrored his tone. For someone who chided his speechwriters when he found a rhetorical question in his speeches, Barack Obama didn’t hesitate to deploy them in private. “Chicago never shut down for a little snow!”

“That’s because we’re awesome, sir,” I replied, affirming our shared Windy City bona fides from a red velvet armchair against the wall.

I’d been waiting with his two assistants, who were already at their desks in what we called the outer Oval Office, a small room tucked between the West Wing hallway and the Oval Office that functioned as a control tower of sorts, where, with the president’s complete trust, they managed his meetings and his arrivals and departures to and from every event on his schedule.

Brian Mosteller, the director of Oval Office operations, was a man equally as fastidious as his boss in his professional appearance, and even more so in his professional demeanor; if he was at his station, he was a touch taciturn, even if he liked you. His passion was the work behind the work—how an event was staged, how a president knew where to go and when, how a speech got from words on a screen to printed pages on a lectern. From his desk, he could see the president at his. Brian was the only person who could boast that, even though he never would.

Ferial Govashiri, born in Tehran, raised in Orange County, California, and barely past thirty years old, acted as the president’s private switchboard and managed the intersection of his personal and professional lives. She sat closer to the door of the Oval Office and balanced out Brian’s reticence with her perpetual cheer and perfectly timed eye rolls.

Obama handed some files to Brian and strode past me. “Come on, Cody.”

I stood up and frowned at my own shoes, the same dull, scarred, brown leather monk straps I wore every day, making a mental note to buy a replacement pair now that a squishy sock betrayed a brand-new hole in the right sole. Sneaking a glance in the gold-framed mirror hung over a console topped with fresh flowers and the morning’s arrangement of newspapers, I scanned my shapeless navy suit, rumpled blue shirt, and fraying black tie. It was my favorite outfit.

I smiled at Ferial, who gave me a wink as I trailed the president of the United States into the Oval Office.

The first time you walk into the Oval, your mouth goes dry. It happens to everybody. You think you’ll be ready for it; after all, it’s the one room in the West Wing that movies and television dramas take pains to get right. But you’re not ready for it. The gravitas of it squeezes the air from your lungs like pressure at the sea floor. The quality of the light is different, sharper somehow, like you just walked onto live television, everyone’s watching you, and everything that’s about to happen carries more weight than it would anywhere else. If your self-importance swells while ascending the White House driveway for a meeting with the president, the Oval Office punctures it right away.

I’d take all the help I could get to avoid face-planting on a big speech—especially one that would tread the thorny subject of race in America.

It’s the best home-court advantage in the world, and Obama pressed that advantage. He kept the temperature a little too warm—pleasant for someone who had spent his first eighteen years between the 22nd Parallels, maybe, but enough to make everyone else fidget. He chose furniture that forced guests to sit awkwardly: If he beckoned you to the antique chair by the Resolute Desk, you’d sit two inches too low and at an angle that made you crane your neck to face him, like a dancer frozen mid-leap; if he motioned you to the caramel couches, plush and deep and maligned by critics as reminiscent of basement hand-me-downs, you could either perch on the edge, back straight, like the class goody two-shoes, or slouch like a child who didn’t want to be called on.

By my seventh year in the Obama White House, though—and my third year as his chief speechwriter—the Oval Office and I had an understanding. I’d set my laptop on the infinity-edged mica coffee table—called out by the New York Times as “extremely contemporary”—and grab a Honeycrisp apple from the one-of-a-kind, hand-turned wooden bowl, then wait to see where he wanted to sit. If he stayed behind his desk, I’d walk over and remain standing in front of him, ignoring the short, rigid chair. If he walked toward his high-backed chair by the fireplace, I’d fluff two of the couch’s overstuffed throw pillows and stack them behind me so that I could sit comfortably, like a normal human. Being in the room didn’t intimidate me anymore.

I couldn’t, however, say the same about my job. To be a speechwriter for Barack Obama is fucking terrifying.

“Okay, show me what you’ve got,” the president said as he settled behind the thirteen-hundred-pound, oak-timbered Resolute Desk. He took a sip of his Lipton with honey and lemon and let out an exaggerated “Ahhhhhhh.” He raised his eyebrows and offered an ironic smile. “Apparently I’ve got a lot of time today.”

I smiled back—not at him, but to myself. His cleared schedule was why I had come to work rather than climb back into bed. The snow day was my scheme to heist as much of his time on the front end of a big speech as I could, and maybe even coax a little more collaboration from him than usual. I’d take all the help I could get to avoid face-planting on a big speech—especially one that would tread the thorny subject of race in America.

*

On March 7, 1965, a group of protesters—mostly young, mostly Black—set out to march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery with a simple demand: the right to vote.

They were led by Hosea Williams, a close advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; and John Lewis, just twenty-five years old but by that point an old hand in the civil rights movement. Just two years earlier, Lewis had been the youngest, most incendiary speaker at the March on Washington. He was also one of the most fearless practitioners of nonviolence in the movement, someone who had bet his life again and again on Freedom Rides and voter-registration drives across the South.

The murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a twenty-six-year-old who’d been shot by police after a peaceful march a couple of weeks earlier while trying to protect his mother from a state trooper’s billy club, imbued the protesters with additional resolve. But the march was rigged from the start: Alabama governor George Wallace had tarred the protesters as illegitimate, calling them socialists and outside agitators, even if, like Lewis, they were children of Alabama; he warned that their very presence would incite violence, even as he ordered his troopers to be violent.

Lewis knew the game and had schooled his unarmed, neatly dressed flock in the tactics of nonviolence before leading them out of Brown Chapel AME Church for the fifty-mile march. They didn’t make it one mile before state police met them on the Edmund Pettus Bridge out of Selma, choking them with tear gas, breaking their bones with batons, and cracking Lewis’s skull so badly he feared he might die.

The governor and the troopers thought they’d won, confident they’d scared the young Americans not only back over the bridge but away from the political process entirely. They were wrong. The photographs of bloodied, unconscious young men and women, Black and white alike, victims of state-sponsored violence in their own land, bounced across news services and ricocheted around the world. They shocked the conscience of the country, and more Americans began to realize such cruelty wasn’t a one-time event but a daily reality for Black Americans who’d been disenfranchised, denied their civil rights, and otherwise subjugated over a century of Jim Crow.

John Lewis, with his head still bandaged, returned to the chapel and told the press that more Americans would join the marchers. He was right: They did, including Dr. King himself. The troopers parted. The marchers reached Montgomery. Their sacrifice shifted public opinion. And their words reached President Lyndon Johnson, who sampled them just weeks later in an address to a joint session of Congress, pledging “We shall overcome” and soon afterward delivering the Voting Rights Act of 1965, building on the Civil Rights Act of 1964—two laws that pulled America closer to fulfilling its founding ideals.

*

Fifty years later, any president of the United States would travel to Selma to commemorate what had happened there. This president of the United States happened to be Black. As John Lewis, by 2015 a U.S. representative of nearly thirty years, would say, “If someone had told me when we were crossing this bridge that one day, I would be back here introducing the first African American president, I would have said you’re crazy. You’re out of your mind.”

Scheduled to speak in just over forty-eight hours at that sacred battleground in Selma was a president of the United States who represented something primal to each side of the conflict.

One might think, then, that a speechwriter’s task would be easy: Let the symbolism do the talking. But to be a speechwriter for Barack Obama was never easy. He never let a captive audience go to waste. I knew he’d demand something more than words just praising Selma as a consequential moment in America’s history. To meet his expectations demanded using Selma as a lens to examine and explain that history.

I’d thought about what the clash on the Edmund Pettus Bridge represented. It was something more than protesters and police. It was something more than one moment in a larger movement.

On one side of that bridge, led by a twenty-five-year-old whose parents had picked somebody else’s cotton, gathered an unlikely crew of Americans. They were young and old, mostly Black, mostly disenfranchised, mostly poor and powerless students, maids, porters, and busboys, burning with the conviction that even though their country had betrayed them again and again, they could change it; together, they could, against all odds, remake America from what it was into what it was supposed to be.

On the other side of that bridge stood the status quo, the power of the state, white men who, even if they weren’t individually powerful or privileged, belonged to a class protected by people who were—a ruling elite who warned them that “giving” equal rights to others would mean ceding their traditional station in society.

It was a simple encapsulation of a clash of ideas that stretched through the full story of Black America but also rang true for every American who, like Dr. King, was “tired of marching for something that should’ve been mine at birth.” The story of justice moved forward thanks to women, farmworkers, laborers, Americans with disabilities, Americans of different sexual orientations, immigrants, the poor and the uninsured, and more. It moved forward through any group of people who had to organize and protest and march and push harder than anybody else—not for special rights, but for the equal rights, basic justice, and fundamental humanity our country had promised from the beginning.

Each of those struggles—each one of those clamorous challenges claiming that the American project is unique on this Earth because it doesn’t require a certain bloodline or that you look, pray, or love a certain way—had riled the established order. And scheduled to speak in just over forty-eight hours at that sacred battleground in Selma was a president of the United States who represented something primal to each side of the conflict—someone who represented change, like it or not.

*

Behind Obama, snow was beginning to dust the South Lawn. He set his tea on the Resolute Desk’s leather blotter and stretched his arm toward me, reaching for his remarks.

“How do you feel about them?”

I’d learned over the years to keep any reservations about a first draft to myself, or he’d dispatch me back to my office to keep working. Without any feedback from him on what I’d already spent days agonizing over, that just meant a few more hours of torturing myself.

“They’re good, sir,” I told him. Besides, if that wasn’t true, he’d let me know.

“Okay,” he said, flipping through the pages without reading them. “I’ll let you know.”

I turned around and padded out of the Oval and through a quiet West Wing, past the Cabinet Room, past the press secretary’s office, and down the stairs to my quarters, tucked roughly underneath the Oval Office.

The idea that ordinary people, without power or privilege, could come together to change their own destiny was a proof point that infused [Obama’s] organizing career with purpose.

I did think the draft was good. But I knew it wasn’t great. Not yet. It was faithful to his take on the American story. What those leaders and foot soldiers of the civil rights movement did to bend America’s trajectory upward was a feat that had fascinated Obama growing up. The idea that ordinary people, without power or privilege, could come together to change their own destiny was a proof point that infused his organizing career with purpose, underpinned his politics, and breathed life into so much of his rhetoric.

Obama wasn’t a perfect heir to that movement; he’d surfed its wake, raised half a world away in Hawaii and Indonesia by the white half of his family. His wasn’t the dominant Black American story—when running for office, he could be dismissed as “too Black” and “not Black enough” at the same time—but his skin color being what it is, I didn’t imagine life cared about the caveats. When he was a kid, his own parents’ marriage would have been illegal in much of the country; when he was in high school, he endured racial epithets; when he was in college, he was profiled by the police. Through all those indignities, he ended up the first Black president of the Harvard Law Review and, well, the first Black president.

If you looked through his eyes, how could the broader trajectory of this country not inspire?

Out of this, I’d cobbled together an argument for the speech:

What could be more American than what happened in this place?

What could more profoundly vindicate the idea of America than plain and humble people—the unsung, the downtrodden, the dreamers not of high station, not born to wealth or privilege, not of one religious tradition but many—coming together to shape their country’s course?

Article continues after advertisementSelma is not some outlier in the American experience. It is the manifestation of the creed written into our founding documents: “We the People… in order to form a more perfect union.”

Not everyone would agree, of course, that protest was the highest form of patriotism. Part of what made a speech like the one in Selma challenging was the presidential high-wire act of finding the right rhetorical path between competing audiences.

A new generation was taking to the streets, marching and impatient for racial justice after a series of high-profile police killings of Black men, joined by allies also hungry for action on economic justice that crossed racial lines, action in the face of a rapidly changing climate, action on a whole host of intersecting issues they felt with all of Dr. King’s “fierce urgency of now.”

There were Americans who disdained the protests, of course; there were also those who expressed sympathy with the young activists and signaled support for their causes but recoiled when that meant changing the status quo—the moderates King dismissed as preferring the absence of tension to the presence of justice.

If Obama went too far in either direction, he’d alienate one of those audiences. But if he walked a tightrope in the middle, he wouldn’t satisfy any.

To consider such trade-offs was part of his job, and therefore part of mine, but it could make me feel like a sellout or, worse, like one of those well-meaning moderates who stood in the way without realizing it.

The longer I stared at a screen, consumed by that worry, the more my thoughts would shrink from the big picture to the pixels on a page. I’d spend too much time rearranging words in sentences and sentences in paragraphs as if the right combination would unlock the one codex to hush the babel of competing audiences and unite them around a simple sentiment: “Wow, what a speech; Obama did it again.”

In my zeal to rise to the moment, all the different audiences a speech had to address blurred into an audience of one: him. Impressing him. Giving him a draft that he’d love. His opinion was the only one that mattered. I’d push myself past my limits to get a first draft right. Giving it to him was like a trip to the guillotine.

*

Barely half an hour had passed before Ferial called and asked me to come back upstairs.

Obama was standing at his desk in shirtsleeves, hands on his hips, about an inch of fresh snow resting on the South Lawn behind him. The swirling flakes erased the Washington Monument.

If Obama went too far in either direction, he’d alienate one of those audiences. But if he walked a tightrope in the middle, he wouldn’t satisfy any.

“Look,” he said, holding a marked-up draft in one hand. “This is well written. I could probably deliver it as is.” He said that a lot. He never meant it. He was setting up for a “but.”

“But we have two days, so let’s make it better.” He started walking toward the couches.

When I’d first started writing for Obama eight years earlier, as an intern for the campaign speechwriting team, it could be crushing to see his edits across the page, his neat penmanship squeezed between paragraphs and along margins, thin lines surgically connecting his additions to the precise places he wanted them sewn in, each one a scalpel to my own self-confidence.

Over time, though, I realized that he worked so intimately with each draft because he was, perhaps more than any president before him, a writer. He was also our editor. His edits meant he liked a draft enough to engage with it, to help push it in the right direction. What he wanted from us, as his team of speechwriters, was a creative partnership, a collaboration where we could make each other better. Where we could take each other to places we couldn’t reach alone.

Before I could ask for guidance, he walked over, sat down next to me, and offered it in a way he hadn’t before.

“You took a half swing on this,” he said. “Take a full swing.”

He was generous to leave open the possibility that I might step back into the batter’s box and connect with the ball. But it stung all the same, mostly because he was right. I had taken a half swing. I’d wrapped myself in fear of what different audiences would think of the final speech and, worse, the fear of what he’d think of the first draft, and that had cornered me into writing what I thought I should, not what I wanted to, something pretty but too safe and sterile to be beautiful.

“What greater form of patriotism is there,” he continued, looking at me, “than the belief that America is unfinished? The notion that we’re strong enough to be self-critical, to look upon our imperfections, and to say that we can do better? Right?”

“Mmm,” I nodded, leaving his question unanswered. I always wished I could come up with what he did.

He stood up and walked toward the three floor-to-ceiling windows behind his desk. “What are we marching for today? What’s the great unfinished business of this generation?” he asked. “Who’s at the other end of that bridge?”

He’d left the edits he’d made in the thirty minutes between my visits to the Oval on the coffee table, and I leaned forward to peek.

He’d added two short paragraphs to the first page, the first consecrating Selma as a battlefield just as important to the American idea as any other:

There are places, moments, in America where the nation’s destiny is decided. Many are sites of war—Concord and Lexington, Appomattox and Gettysburg. Selma is such a place.

Then he elevated the battle fought there as critical to America’s destiny:

It was not a clash of armies, but a clash of wills; a contest to determine the meaning of America.

I sat back into the couch. Damn. That was it, right there—the whole thesis of the speech:

It was not a clash of armies, but a clash of wills; a contest to determine the meaning of America.

Hell, in just twenty words, he’d described everything at the root of our political life. The speech clicked for me in a way it hadn’t before. I’d had days. He’d needed thirty minutes.

In just twenty words, he’d described everything at the root of our political life.

Obama hadn’t seen me looking; still speaking, he was staring out the windows at the accumulating snow that made the Oval Office glow even more brightly than usual.

“We are still engaged in that fundamental contest between what America is and what it should be,” he said. “Selma is about each of us asking ourselves what we can do to make America better. That’s the American story. Not just scratching for what was or settling for what is—but imagining what might be. Insisting we live up to our highest ideals. So let’s translate Selma for this generation. Let’s give today’s young people their marching orders.”

He turned back toward me, and I took the signal to stand up. “There’s always been a tension between those high ideals of our founding and how short we fall of them,” he said. “We’re at our best when we mind that tension. When we work to close that gap. Because we believe we can. That’s what makes America exceptional.”

He grinned at me and pointed to the draft on the table. “Go write that up.”

_____________________________________

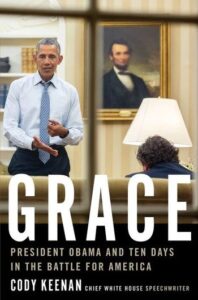

Excerpted from Grace: President Obama and Ten Days in the Battle for America by Cody Keenan. Copyright © 2022. Available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Cody Keenan

Cody Keenan rose from a campaign intern in Chicago to become chief speechwriter at the White House and Barack Obama’s post-presidential collaborator. A sought-after expert on politics, messaging, and current affairs, he is a partner at leading speechwriting firm Fenway Strategies and teaches a popular course on political speechwriting at his alma mater Northwestern University. He lives in New York City with his wife Kristen and their daughter Gracie.