How Photographing a Dumb Paper Bag Led to Writing

a Novel

Anna Cox on the Radical Act of Being Seen

Everything I needed to know about writing and editing a novel I learned by photographing a dumb brown bag.

I teach photography and I also write but I don’t separate the two disciplines. Photography and writing are both conjuring arts, they share the communicative tricks and troubles of sequencing scenes, stopping and pacing time, framing space, and figuring out what to include and what to exclude. Both are make-believe processes that can remake norms and shift beliefs.

As I write, I visualize the scenes as if I were taking pictures. I choose the lens that will communicate what I need and I scrutinize the background for distractions and misdirection. I worry about how close or how far I need to be from my subjects while paying attention to who who is lit and who is shadowed. Using depth of field, I flatten space or expand it and changing shutter speeds, I accelerate time or stop it. I don’t know what people’s mistaken beliefs about novel writing are, but people think photography is all about technology—how fast is your memory card and how big is yours lens—but most of that stuff is useless. Extraordinary images can be created with a crappy shoe box and a piece of tape, and the fanciest equipment can’t bestow ideas, let alone compelling ones. What matters, in fiction and photography, is how you see and what you do with what you’ve seen.

To remind myself of that, I keep a brown paper grocery bag taped to the wall above my desk. The bag is from a photography assignment that I made up when I taught at a small public university in Virginia. The bag assignment challenged and changed the photographers in the class and it continues to challenge and change how I write.

The assignment is morbidly simple. Each student receives a brown paper bag, the kind and size used to hold groceries. The assignment is eight-weeks long and the parameters are to make 300 unique images of the bag and only of the bag. At the end of each week there is an in-progress critique and during those workshops, the class uses magnifying loupes to examine tiny rectangular pictures. Any image that is visually or conceptually similar to any other image won’t count for either student towards their required 300 shots.

On the first day of the assignment the students looked at their bag and believed they saw it and understood it, because really, what is there to see? How hard can it be? A kraft paper body, glued seams, one end open and the other end closed. Done and done. At the end of the first week, students pinned their contact sheets to the wall. They were in good moods joking now that we’ve solved this can we take the next seven weeks off? After thoughtful debate most students left with only about 10 images towards their required 300.

No one wants to photograph a brown paper bag for eight weeks, let alone the same brown paper bag just like no writer wants to write their draft over and over. By the second week, students were annoyed. To their pleas of, I’ve done all I can do, I’d say, No, you haven’t. Switch your lens. Lots of figurative stuff can be said about lenses, everyone writes from their own perspective, but that’s not what I mean, I’m speaking about lenses in a flat and technical way. Lenses focus a picture and control the angle of view. A wide-angle lens produces an angle wider than the human eye sees, like in landscape photography or drone footage. A normal lens mimics standard biological perspective while a telephoto lens magnifies and brings far away objects close. Sequencing gestures and scenes in a novel is like sequencing a group of images—too many close-up tableaus don’t give a viewer context, but too many wide-angled shots leave a reader hungry for specifics.

My novel alternates between three women who are impacted by the same absurd tragedy. Ruth is a widow, still grieving her long dead husband. One night Ruth climbs into her husband’s recliner looking for anything that’s left of him, spare change or crumbs that fell in the cracks because that’s where he ate graham crackers with butter. I wanted the reader to feel shoved and stuck in that chair. I didn’t want them to see anything other than tufted buttons and hands thrusts behind and under cushions. It was a desperate moment in a narrow and private space. Nothing else could be in focus because it needed to look and feel like everything else in the room fell away, an obviously telephoto lens scene. Later in the novel, Ruth hits bottom in a very public space, a grocery store. I imagined that scene through a wide-angle lens because the expected and sweeping banality of grocery store aisles lure the reader into a familiar space and doesn’t prepare them for what happens next which is Ruth, standing in the middle of the produce aisle, wearing a nightgown in the middle of the day, spitting on all the lettuce.

In weeks four and five, the class contemplated mutiny. These bags are dumb, they said. Stop looking away, I suggested. Four years and innumerable drafts into my book I felt the same way. Is there a word for self mutiny? It’s probably quitting or giving up. Looking away is a lousy creative strategy. Refusing to look more and refusing to stare deeper and longer produces shallow pictures and surface fiction. When I’m stuck in a draft (which is most of the time) I ask myself, what am I not seeing? Do I need to be closer? Do I need to step back? Why am I using this lens? When I can’t figure it out, I write variations using each lens because the point is to keep looking, without preconceived notion, until I’m ready to see what needs to be told.

By week six, students realized the ridiculous inversion of the time it takes to create images versus the time it takes to consume images. In week seven, they understood the power of shifting their gaze; they stopped blaming the bag and started telling their stories because they figured out the bag was just a prop that could have been anything. They photographed from underneath and inside, from above and below. In that week’s critique they presented images of small folds and big rips, they figured out how to communicate the volume of the bag with only a corner. Using sweeping width, they dwarfed the bag and made it seem abandoned. They made the bag’s zigzags feel sharp, like razor teeth. Same dumb bag but very different effects. For the final critique in week eight, the students organized an exhibition of 300 images each. They turned their bags inside out, set them on fire and photographed the ashes.

My novel begins through a normal lens. I own Vixen photography, and my business is looking at your business. My customers carry the pyramids in their pockets and tuck the fiery sun underneath their pillows. In a photograph, distance disappears and past fuses to present; it’s time travel on the cheap. No ticket, no passport. Stop a rocket with your pinky, hold a flame and never blister. Portable enchantment, rolled up and lighttight. In another time I would have been an alchemist, but in 1979 people buy their gold at the mall so I perform a different kind of magic. I transform negatives into positives.

Transforming negatives into positives isn’t a hackneyed prop, it a technical reality. It’s why I study and write about photography because writing fiction about photography might reveal some truths about how we envision each other. I keep the bag above my desk to remind me to hold firm and not look away. Looking away, in fiction or on film, is refusing to acknowledge things as they are and averting sight stops insight. That dumb brown bag reminds me that problems in fiction and photography are the problems of the world—problems of how we portray ourselves and how we see others—and those cannot be solved until they are fully, radically seen.

__________________________________

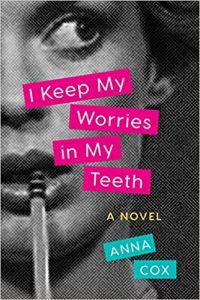

I Keep My Worries in My Teeth by Anna Cox is available now from Little A Publishing.

Anna Cox

Anna Cox teaches photography at universities in Canada and the United States. I Keep My Worries in My Teeth is her debut novel.