How One Writer’s Brush With Covid Temporarily Robbed Her Of Her Career

Alice Feiring on the Unsettling Prospect of Writing About Wine With No Sense of Smell

Death was the most frightening possible outcome of Covid, but right up there for me was anosmia. A wine writer who couldn’t smell, let alone taste? Who would ever trust me? It was my first day with the virus and the papery cardamon pod sat in my palm and mocked me. I sniffed it. No lime-dosed, musty-but-sweet green scent. Nothing.

Feverish, I ran to my fire escape and pinched a few leaves off my mint plant, scrunched them up to release their potent oils and with the edge of panic, shoved the blob up my nostrils. All I could get was a faint alpine whiff.

Immanuel Kant called smell the “most ungrateful” and “most dispensable” of the senses. But according to the Zohar, the Jewish mystical interpretation of the Bible, the sense stands on a higher plane than wisdom and understanding. It is intimacy and instinct (just ask any dog). The power of that sentiment resonated as I ransacked my spice shelves, trying to detect the tiniest scintilla of bouquet. My life in aromatics rolled past me.

For those of us who live by fragrance—perfumers, wine, food and booze devotees of every stripe—Covid’s anosmia hits the terror bullseye and our livelihood.

Smell has always my life’s lens. From the time I could walk, I entered every room nose first. At that young age I imitated my white-bearded grandfather saying, “Vat I smell.” He too had a hypersensitive beak. Eccentrically, he sequestered miniature bottles of perfumes in his underwear drawer. He would pull them out and we would sniff them together. He spoke little English, I spoke no Yiddish—aroma became our common language. The first smell that made an impression on me was a violet found on the lawn of the family’s ancestral crappy split level in Baldwin, Long Island. There near the rhododendron were the tiniest of petals with the tiniest of mesmerizing smells.

Then there was food. Nothing got past my lips without lifting it to my nose. My parents ridiculed me, “Do you have to smell everything before you eat it?” Laugh they might, but I was the only family member not heaving into the toilet that night after refusing to eat what was to me, a very dead trout in a Southern diner. My grandfather had unwittingly given me world-class nose training, critical to my future in wine.

For those of us who live by fragrance—perfumers, wine, food and booze devotees of every stripe—Covid’s anosmia hits the terror bullseye and our livelihood. That’s why I had made sure to outpace the disease for two years. With a freelance life, it was easy. The big walk around tastings—big tables loaded with wines for sampling, were replaced by my evaluating wines in my kitchen, spitting into the sink and taking notes. Travel? Before March 2020 I was on a flight every five weeks to see visit winemakers and their vineyards, that wasn’t happening. So, like the rest of the world, I was grounded.

Events I used to lead in front of a live audience now were held on Instagram or over Zoom and there was plenty of time to devote to my natural wine newsletter, and my own writing, the memoir, a new novel. In a way, this time was not unlike an artificially imposed writer’s retreat. When masks fell away and the in-person events returned I mostly rejected them as too risky and my social abilities were rusty. But tasting paid my rent. Feeling fortified after my second booster, I accepted a promising invitation, headed for Austria, and slipped into denial about the risk.

Even before touchdown at JFK, my throat was sore, my skin on fire. The week of expectorating wine in non-socially distanced crowds, connecting with people I hadn’t seen in two years, feeling life, laughing, breathing in suspect droplets as I hadn’t in so long, did me in. After I lugged my bags up the five-floors to my apartment, the double pink lines on the home test confirmed what I knew.

My fever rang in at 102-degree, but I had to try wine. The usually luscious 2020 Thibault Ducroux beaujolais assaulted my mouth as if I had dumped a box of Diamond Crystal on my tongue. I knew the nose was to follow which by the time I woke up, it had. My only superpower had dimmed. Why hadn’t I insured my nose for those million bucks like a famous critic had done?

Yet, in the calm moments sandwiched in-between my “what if” terror, I was fascinated. Was this episode of nasal paralysis the way many navigated life? The lead author of a 2013 study on the topic, Hiroaki Matsunami told me, “One tiny mutation of an amino acid on a nasal receptor gene can affect our experience from painful, pleasurable or neutral.” I knew we all perceive smells differently, but I hadn’t realized just how dramatic it all was. No wonder when I wrinkled my nose at a rancid nut or oil, others looked at me as if I’m psychotic. When leading wine tastings I was always asked, “What do you smell?” Invariably I stammered, pushed for the participant to find their own words and revelations. Reading that paper in conjunction with my now silenced ability made me realize, they really wanted to know. And I should tell them.

It took losing my olfactory ability to understand that thanks to genetics, just how good a machine sat on the middle of my face.

I know that I don’t have the most precise instrument in the business, but it took losing my olfactory ability to understand that thanks to genetics, just how good a machine sat on the middle of my face. I swore that I’d greet my audience with more compassion.

Intellectually intrigued for sure but I wasn’t ready to roll over without a fight and before my fever subsided, I sank my deviated septum into just about everything, willing my dead nostrils to wake up and smell the coffee. I circled my apartment, Groundhog Day style, until I realized I needed a nuclear strategy—perfume.

Like my grandfather, I too hoarded little bottles. Over the years I’ve specifically collected violets wherever I found them no matter which form they took: Vintage American and French violet candies, violet perfume from Spain, any perfume that had violet, even if they were synthetic. Years back I scored a petite vial of Annick Goutal’s La Violette on eBay. I only need a teensie one because I would never wear it, I would only sniff it, time-to-time, to be transported to a potent violet I smelled in a Barolo back yard on a magical afternoon, or a memory or just an uplift. But this time it was medicinal.

I dribbled the scent right onto my wrists. The Zohar suggests that scent is the bridge that connects the spiritual and physical world and every time I deal with those little bottles, of course I feel as if I’m speaking to my grandfather. Over the next few days, every time I woke up from a feverish nap or long night’s sleep, I hunted my arms to find it. At first, I marveled at how subtle, almost pleasing it was.

Near one dawn, I could smell its complex and layered sweetness with some familiar undertone of rot as it mingled with my oils. The more I smelled it, the more I could smell. I finally had to scrub the scent off of me it had become so obnoxious. My brush with anosmia was blessedly over within a week, and I have not stopped pointing my snout up ever since, happily lapping up whatever was carried on the wind. Whether or not it was my grandfather guiding me back to our shared story through the subjective and philosophical power of perfume, or that the virus simply released my nose from captivity, it didn’t really matter.

___________________________________

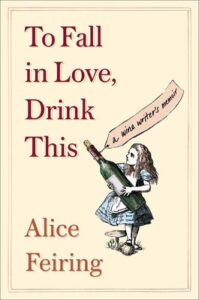

To Fall in Love, Drink This: A Wine Writer’s Memoir by Alice Feiring is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Alice Feiring

Journalist and essayist Alice Feiring was proclaimed “the queen of natural wines” by the Financial Times. Feiring is a recipient of a coveted James Beard Award for wine journalism, among many other awards. She has written for newspapers and magazines including The New York Times, New York magazine, Time, AFAR, World of Fine Wine, and the beloved winezine, Noble Rot. She has also appeared frequently on public radio. Her previous books include Natural Wine for the People, Dirty Guide to Wine, For the Love of Wine, Naked Wine: Letting Grapes Do What Comes Naturally, and her controversial 2008 debut, The Battle for Wine & Love or How I Saved the World from Parkerization. Alice lives in New York and publishes the authoritative natural wine newsletter, The Feiring Line.