How Not to Lose Hope: Alternate Histories and the Real World

Paz Pardo on Living in a World of Continuing Calamities

Alternate histories have long been a staple of my comfort reading diet. When the going gets rough—the future looks uncertain, the present unstable—I have always been happy to decamp to a hypothetical world. But I’m tricking myself when I think it will be a great escape. These books’ imaginary times always bring me firmly back to reality. They change how I see real life, help me articulate what I haven’t been able to name. They remind me that history may seem inevitable in hindsight, but the future is still undefined.

Take Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist, taught me another way to read the world I live in. I discovered it while I was embarking on a complete overhaul of my novel—an alternate history noir—trudging through revisions that made me wonder why I’d started writing at all. I was thrilled, then, to close my computer and be shunted into a parallel Big Apple, where elevator inspection is a sacred charge promising to lift society from the “stunted shacks” of the present into a glorious future of verticality.

The book exists in the nineteen-gumshoes: a world of radios and automats, narrated in a gravelly noir voice. The premise was hilarious, but it wasn’t tongue-in-cheek; it was more hand-in-glove, a quick handshake in a dark alley pulling me into a joke that was serious as sabotage. Not so much ironic detachment as conspiratorial invitation.

History may seem inevitable in hindsight, but the future is still undefined.

But what, exactly, was The Intuitionist inviting me into? In this brave new (old) world, the places that Whitehead leaned on my understanding of the real world carried a special weight. Take, early on, a description of the hairdo required by the Guild of Elevator Inspectors in its early days: a “utilitarian mishap” that “project[s] honor, fidelity, brotherhood unto death. […] Some of the younger inspectors have started wearing the haircut again. It’s called a Safety. Lila Mae’s hair parts in the middle and cups her round face like a thousand hungry fingers.”

Whitehead does not actually describe the Safety, opting instead for its ideas—but I can still picture it, and how different Lila Mae’s hair is. It’s different because she’s a woman; it’s different because she’s Black. It does not confer Safety upon her. As a reader, I bring my knowledge of the politics of the real world to the book, and I know that this paragraph is not simply describing the fashion in coifs; it lays out the perilous minefield of racism and sexism that Lila Mae walks daily.

This alternate history Whitehead is building is a few degrees off from reality, so when knowledge from the real world comes in it is not just a familiar fact. Under the book’s neon lights, it seems new. Whitehead chooses what he pulls from reality, and that choice is more meaningful than if he were writing a straight historical fiction; it emphasizes what he wishes I would pay attention to, nudging me to change the way I pay attention in daily life. Asking me to look closer at the choices that delineate what bodies are welcome where. Teaching me another way of reading the world.

In Jo Walton’s My Real Children, I found an encapsulation of what terrifies me in our current political moment: the way that the previously unthinkable has become accepted. Written for those of us who cannot get enough of alternate history, the book’s protagonist lives through not one but two hypothetical timelines.

In one, the Cuban Missile Crisis becomes the Cuban Missile Exchange: the Soviets nuke Miami, the US takes out Kiev. In the aftermath, all parties swear it will never happen again, but the seal has been broken. Every decade, another mushroom cloud rises. Cities are lost, whole ecosystems poisoned. Thyroid cancer explodes. But life goes on—the book’s domestic drama unfolds in rooms identical to those that we live in.

Near the end of the book, Pat’s granddaughter Sammy brings the news of nukes wiping out Tel Aviv and the Assam Dam. When Pat points out that the thought of using them was once unconscionable, the teenager responds: “Well, people have them, they’re going to use them,” and then shows Pat a photo of her crush on her phone— “Isn’t he smooth?”

Sammy brings this tidbit of current events to her grandmother like a sheet of homework, a conversation starter she’s hoarded to share—but shows no sign that this news is particularly pressing or terrifying to her. Nuclear explosions have become a fact of life, so why worry too much about them? The unthinkable becomes inevitable, and once inevitable, acceptable. Lord grant me the wisdom to accept the things I cannot change. They’re going to use them, so might as well focus on the things I can change.

The unthinkable becomes inevitable, and once inevitable, acceptable.

Sammy’s turn to her phone, to the more pressing issue of the boy she likes, is not just teenage narcissism. It is nihilism disguised as pragmatism. It is precisely this creeping nihilism that this alternate history lays bare—especially since in the book’s other timeline, the protagonist is a dedicated volunteer with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. I am reminded by that juxtaposition that none of this is inevitable. It is not only fictional, but a kind of fiction that insists on its irreality as I track how far it has diverged from real life, how it mixes my quotidian experience with things that have never happened.

I read the book in early June 2022, in the shadow of the leaked Dobbs opinion. Waiting for the unthinkable to become inevitable. The Wall Street Journal published an op-ed saying there was no way the court would come for contraception or same-sex or interracial marriage next, using the same language they’d used to dismiss fears about abortion rights after Kavanaugh and Coney Barrett’s rushed appointments. Over and over again, as the summer turned to fall and the news stories about the ruling’s effects dried up, I thought about that moment in My Real Children. Unthinkable. Then inevitable. How long until acceptable?

Then I found Rachel Heng’s The Great Reclamation, which reminded me that stories of inevitability should never be accepted at face value. Heng’s book (out March 23rd) follows the community of a kampong (village) on the coast of Singapore as the nation throws off the colonial regime. Heng writes a story that can be read as either straight-historical or something more magical, with a set of disappearing islands—which can only be found through the protagonist’s guidance—at its center. With my taste for genre, I read their mystery as fantastical, their slippery presence twisting the tale told on the page a few degrees away from the true past. The question of the inevitability—or lack thereof—of history vibrates under every action in the book, heightened by the islands’ ambiguous permanency.

This destabilizing of the inevitable is especially clear in the novel’s treatment of the Great Reclamation project, from which it takes its name. An actual undertaking begun in the 1960s, the Great Reclamation expanded the island with over fifteen hundred hectares of landfill. At each step, the book shows me the roadblocks to its execution—one of which is the kampong lying in its path. The government builds flats for the kampong’s residents, but doesn’t want to be seen forcing them to relocate. It turns to rhetoric of inescapable progress to convince the populace.

Alternate histories remind me that the story of inevitability should always be questioned.

Heng takes care to show how presenting these plans as unstoppable gives them momentum. Listening to the radio, the owner of the kampong’s shop becomes certain the government “would have their way,” and reasons: “He did want to retire. […] If moving to the [government] flats would make that possible, then he would accept the inevitable, and he would go.” Here, Heng directly ties the perception of inevitability to the character’s choice: since the government would have their way anyway, he’ll go along.

As a reader, I know that this Great Reclamation could be thrown for a loop if enough of the kampong refuses the flats, but the characters don’t have that information. Thus seeming inevitability becomes true inevitability, until (as Heng writes) there is “nothing to be done, all were fossils, all was calcified history.” Even as the book carves its way back from speculative territory to the actual history of the emerging island-nation of Singapore, it continually reminds me that this was not necessarily the path of least resistance; this was a path that one group of people proposed and another accepted.

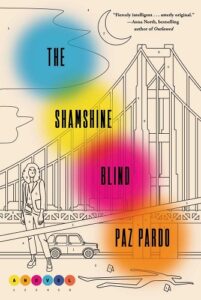

I’ve lived in an alternate history for the last eight years, as I’ve slowly built the world of my own novel, The Shamshine Blind. Here, Argentina won the Falklands War in the ‘80s, using weaponized emotions to vault itself to superpower status. In this 2009, the US is an also-ran and those weapons have become integrated into the fabric of life, as colorful pharma and street drugs (want to feel happy? Pop a Sunshine Yellow pill. Want to make your ex suffer? Slip them some Slate Gray Ennui).

I’ve pulled from my real experience of living in countries with foreign military bases next to their biggest cities, where double-digit annual inflation is the standard, not the exception. I’ve allowed the characters to believe their world was inevitable. Hoping the absurdity of the accepted in my imaginary world will give the reader space to reflect on the absurd things we accept in ours.

We live in a timeline full of unthinkable things made to seem inevitable, where the calcified history that led to the present blinkers my vision of what is possible. A time of mass shootings, unlivable wages, police killings, climate catastrophe. Nihilism costumes itself as pragmatism, cites broken political systems—what’s to be done, anyway?

Alternate histories remind me that the story of inevitability should always be questioned. That accepting the things I cannot change is part of what makes them seem inevitable. That I can choose to pay attention. Choose to imagine and work toward a better world. The first step is to remember that history is always being written.

__________________________________

The Shamshine Blind by Paz Pardo is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Paz Pardo

Paz Pardo is an Argentine-American novelist and playwright. Her debut novel, The Shamshine Blind, came out in 2023 and was a CrimeReads Best Speculative Crime pick, Library Journal Best SF/Fantasy pick, and San Francisco Chronicle Best Book pick that year. Her work has been published in the New York Times, CrimeReads, and LitHub (among others). She received her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers, her undergraduate degree from Stanford University, and is the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship. More at www.pazsays.com.