I don’t think it is a coincidence or an exaggeration to say that down through time and certainly over the past century women writers, such as Rachel Carson, have produced an overwhelming number of change-making stories told through narrative, more perhaps than men. Women who wanted to be journalists during the time that London, Sinclair, Hemingway, Orwell, and others were publishing and enjoying attention and praise always had two missions in mind.

There was the story they wanted to write that might create change, and an even more challenging mission: to penetrate the white male journalist fortress that was dead-set against offering them opportunities to write their stories, because they were women.

Until very recently, women journalists were not considered worthy of writing serious stories. Even in the 1960s, as Wolfe and Talese were beginning to pioneer their new journalism, it was not new enough to include women. Gail Sheehy’s book Passages, about the predicable crises people experience as they age, published in 1977, was on the New York Times best-seller list for three consecutive years, and the Library of Congress named it one of the ten most influential books of our time. Writing in The Cut a few years before she died in 2020, Sheehy remembered the struggle and the challenge for women journalists in 1960s and 1970s: the atmosphere of forced division, the lack of acknowledgement of the work they produced, where they were positioned in the newsroom.

“When I was a news chick at the New York Herald Tribune,” she wrote, “sequestered in the flamingo pink Women’s Department (as were all the paper’s female journalists in the ‘60s), the male reporters I might encounter in the elevator looked straight through me, probably assuming I was somebody’s stenographer.”

One specific elevator ride, however, led to an opportunity to write, after she asked the tall sandy-haired reporter: “Mr. Wolfe, what’s it like, writing for Clay Felker?” Felker was the editor of New York and later became the editor of Esquire and later yet of the Village Voice. Wolfe, to his credit, encouraged her to find out from the source—Felker himself.

“I crossed the DMZ into the City Room, all bobbing heads of white men with crew cuts (except for Bad Boy [Jimmy] Breslin and his tangle of black curls) and tapped on the door of the editor-in-chief. Clay Felker’s booming voice came back: ‘Where did you come from? The estrogen zone?’”

Even ten years later, in the New Journalism anthology of the twenty writers selected as the best new journalists of the era, edited by Wolfe and E.W. Johnson, only two women were included: Joan Didion and Barbara Goldsmith, who wrote may books in her long career, including the classic best seller Little Gloria…Happy at Last, about Gloria Vanderbilt’s difficult coming of age, which became both a movie and a TV series.

But long before Sheehy was confined to the “estrogen zone,” women journalists were persona non grata in newsrooms, not included on mastheads and not legitimately acknowledged in bylines. But women managed, through force of will and ingenuity, to do good in the world or for the world by hiding who they were, often assuming a male identity—or disguising themselves as someone else. And not only were they writing narrative, employing the techniques of fiction writers, as Wolfe had described, but daringly and courageously involving themselves in their stories, diving into unknown territory in situations that men could not or would not confront. And they worked really hard at it because they were, in many cases, not wanted and certainly not appreciated as women. But they not only made history; they changed history. And in order to do that, they often changed their names.

*

There are three statues at the Pittsburgh International Airport, through which I mostly travel from home to wherever and back. Two are heroic examples of the city’s history. First, George Washington, the father of our country, who initiated the French and Indian War near Pittsburgh and helped built Fort Necessity and Fort Duquesne; second, the famed Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris, making his incredible immaculate reception in a divisional playoff game against the Oakland Raiders. If you are a Pittsburgher or an NFL fan, you will know the exact details of this improbable catch he made and the thirty seconds that followed, leading the Steelers to their first of four Super Bowl victories. If you’ve never heard of the immaculate reception, you ought to look it up, unless you want to be perceived as a fool while visiting the town.

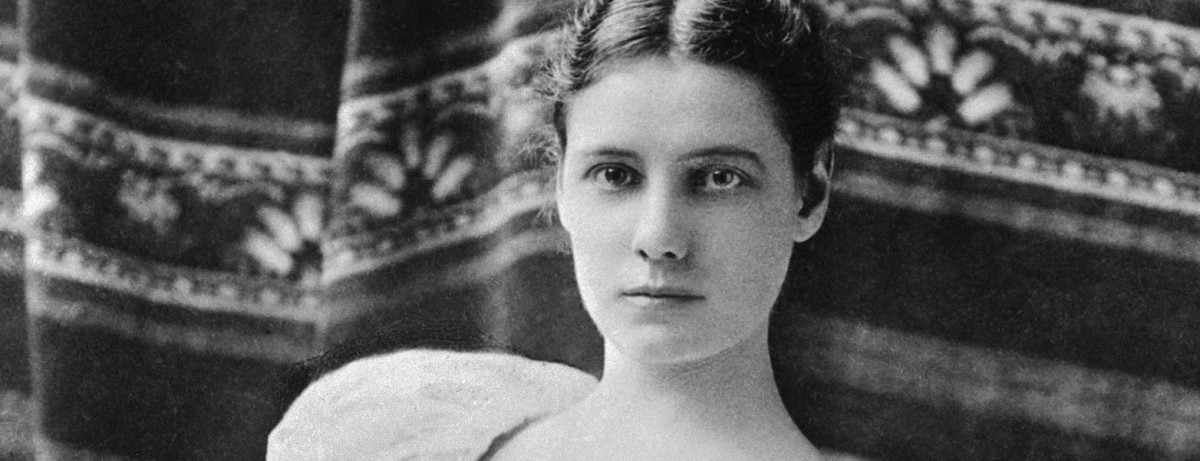

The third statue is quite a contrast to George and Franco and somewhat of a surprise and maybe a bit misleading: A young woman, twenty-four years old, with short brown hair, wearing a neat, tailored plaid coat and black leather gloves, with a small woolen hat on the back of her head. She is carrying at her side a small leather satchel. She was a journalist who early in her career worked as a reporter for two local newspapers, but achieved greatness after she left Pittsburgh in 1887 to work for the New York World.

Her name, when she began her journalistic career in Pittsburgh, was Elizabeth Jane Cochrane. But by the time she left the area where she had grown up, she was known as Nellie Bly. It was a name chosen by her editor, taken from a Stephen Foster song. So, a man was able to name her and forge her identity. Women were not allowed to write under their own names at that time, because—according to their publishers and editors—being weak and helpless, they would be much too vulnerable to the wrath of the men who were subjects of the undercover stories they wrote.

Bly—or Cochrane—became famous worldwide by circling the globe in a record-breaking seventy-two days, leaving the fictional character Phileas Fogg, the protagonist in Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873, in the dust. The statue in Pittsburgh depicts her outfit on the day of her departure, on November 14, 1889. The satchel she carried, the size of a small toaster oven, held everything she needed for those seventy-two days of journeying by ship, train, and horseback, including her writing materials and a small flask with a drinking cup. Bly had confronted a great deal of resistance when she proposed her around-the-world plan to her editor, who told her, “No one but a man can do this,” to which she replied: “Very well, start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.”

She won the assignment and the race against Fogg. Her editor was well aware that Bly could do anything she set her mind to, not despite the fact that she was a woman, but because of it.

For her first big story for the New York World the previous year she exposed the horrific living conditions of the patients of what was then known as an “insane asylum” on Blackwell’s Island, now Roosevelt Island, in New York. Her plan was to get herself committed to Blackwell’s by convincing officials that she was insane, a performance that might have earned an Academy Award if she had been making a movie.

In preparation, Bly rented a room in a tenement boarding house, the Temporary Home for Females, on Second Avenue in the East Village in New York. In her room, she practiced how to look and act insane, as she would later describe in the first ten articles for the World: “I flew to the mirror and examined my face. I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection…I read snatches of improbable and impossible ghost stories, so that when the dawn came to chase away the night, I felt that I was in a fit mood for my mission.”

When she was satisfied that she was well-prepared to prove herself insane, she had momentary second thoughts. “Who could tell but that the strain of playing crazy and being shut up with a crowd of mad people, might turn my own brain, and I would never get back. But not once did I think of shirking my mission. Calmly, outwardly at least, I went out to my crazy business.”

Her story, the first in a ten-part series, begins that way—from acting out in the boarding house to being taken by police to the Essex Market Police Courtroom and acting out again so that a sympathetic Judge Duffy allowed her to move one more step forward—to be admitted to Bellevue Hospital’s “pavilion for the insane.” And then finally, after another day of examination and acting out, sent where she wanted to be all along, Blackwell’s—the focus of her stories about the city’s treatment of the mentally ill—where she was immediately undressed and prepared for confinement. She wrote:

The water was ice-cold, and a crazy woman began to scrub me. I can find no other word that will express it but scrubbing. From a small tin pan, she took some soft soap and rubbed it all over me, even all over my face and my pretty hair. I was at last past seeing or speaking, although I had begged that my hair be left untouched. Rub, rub, rub, went the old woman, chattering to herself. My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold. Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head—ice-cold water, too—into my eyes, my years, my nose and my mouth. I think I experienced some of the sensations of a drowning person as they dragged me, gasping, shivering and quaking, from the tub. For once I did look insane…They put me, dripping wet, into a short canton flannel slip, labeled across the extreme end in large black letters, “Lunatic Asylum, B.I., H. 6.” The letters meant Blackwell’s Island, Hall 6.

Nellie Bly’s “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” capturing her experiences at Blackwell’s Island, immediately made a difference, as she wrote in the introduction to her series: “I am happy to be able to state as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appropriated $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane. So, I have at least the satisfaction of knowing that the poor unfortunates will be the better cared for because of my work.” Like Rachel Carson, a fellow Pittsburgher, her mission forced change. Although not enough change to allow women to write as women under their own given names.

Picture a scene two years after Bly’s sensational exposé: A helpless young girl in old tattered clothes staggers and stumbles across a busy street in San Francisco’s Mission District and suddenly faints in front of a moving carriage, which nearly runs her down. The police are called to move her out of the street, but when she resists, they club her with wooden batons, throw her on the hard floor of a horse-drawn buggy, and transport her to the emergency room of a nearby hospital. The staff at the hospital, men and women both, are dismissive and annoying, and pepper her with lewd and insulting remarks. She is treated coldly and quickly, no real examination provided, medicated with a concoction of mustard and hot water to precipitate vomiting—and soon thereafter released.

Two weeks later, the San Francisco Examiner, owned by William Randolph Hearst, published a five-part series of stories capturing and documenting the brutal and insensitive treatment of women in hospital emergency rooms. Like Bly’s work, this dramatic account of treatment led to the establishment of a well-trained ambulance service in the city—for men and women. Later, this writer—identified as Annie Laurie—was to become the first woman journalist to cover a prize fight. Later still, disguised as a boy, she was the first reporter on the scene to cover the horrific Galveston hurricane of 1900 in Texas.

And then in July 1888, Nell Nelson, a young schoolteacher in Chicago, wearing a brown veil and a tattered coat, began taking a number of jobs in factories, stitching coats, shoe linings, and shirts at the Excelsior Underwear Company for eighty cents a dozen. It was hard work, to say the least—a lack of ventilation, poor lighting—and it was bloody hot. And as it turned out, the first dozen shirts she sewed were free—at least to her employer. For, she learned: Rent for the sewing machine she was using was fifty cents. And the thread for the shirts she sewed? An additional charge of thirty-five cents. But if that wasn’t bad enough, Nelson and her fellow employees were insulted and berated. And not just at Excelsior; it was no different wherever she went. Her series of stories ran for nineteen straight weeks, doubling circulation for the Chicago Times. And then there was Eva Gay, who, in disguise, infiltrated an industrial laundry to document the unhealthy conditions for the women who labored there.

These writers made an impact; they changed lives because of their personal narratives, but despite their bylines, few readers knew who they really were. But as Kim Todd wrote, the names these women used, their bylines, “were often fake. Stunt reporters relied on pseudonyms, which offered protection as they waded deep into unladylike territory to poke sticks at powerful men. Annie Laurie was really Winifred Sweet; Gay was Eva Valesh; Marks was Eleanor Stackhouse…. ‘Many of the brightest women frequently disguise their identity, not under one nom de plume, but under half a dozen,’ wrote a male editor for the trade publication The Journalist in 1889. ‘This renders anything like a solid reputation almost impossible.’”

All of these boundary-breaking reporters were forced into a similar identity deception. And the treatment of some of these stories, as serious as they were, was often trivialized with inappropriate illustrations of billowing skirts and wild wind-whipped hair, depicting the helplessness of the “opposite” sex. Even the ways in which women writers were referred to and labeled were often demeaning. Laurie, Bly, and their ilk were treated as novelty writers, performing tricks to get access to their stories. In fact, they were called as a group, as Todd reports, the “stunt girls.”

The personalization, the confessional aspects of these stories, would, nearly a century later, become a flashpoint of the creative nonfiction debate and movement.There was another label, which as most ironic, especially since it wasn’t actually the “stunt” that captivated readers and motivated political and social action, but the voices, observations, and feelings—the deep-seated personal observations of the writers and the descriptions of the characters they captured. When the stories were especially poignant, critics and colleagues referred to the women who wrote these stories as the “sob sisters.”

The personalization, the confessional aspects of these stories, would, nearly a century later, become a flashpoint of the creative nonfiction debate and movement, when writers like James Wolcott demeaned them in Vanity Fair, characterizing their emotional honesty and intensity as “navel gazing.” But at the time, the confessional aspects of their work weren’t seen as worth debating—or criticizing. This whining and wailing about the ills of the world, the man’s world, was to be expected coming from women. Journalists generally did not take the “girls” seriously. They were simply a means to the end. They used a woman to get a story that would not be possible for a man to get, a story that would sell papers and advertising and attract attention and praise—perhaps until Ida Tarbell.

Ida Tarbell, an investigative journalist and lecturer, became as famous and as influential as Upton Sinclair and others of what Theodore Roosevelt had labeled as the “muckraking” crowd. The History of the Standard Oil Company by Tarbell was first published as a nineteen-part series in McClure’s Magazine and then in 1904 as a two-volume book. As one critic described her reporting, Tarbell “fed the antitrust frenzy by verifying what many had suspected for years: the pattern of deceit, secrecy and unregulated concentration of power that characterized Gilded Age business practice with its ‘commercial Machiavellianism.’” Tarbell was prolific, to say the least, and most enjoyed digging deep into her subjects for long periods of time, as in her series of articles for McClure’s about the life of Napoleon and an eye-opening twenty-part series on Abraham Lincoln to which she dedicated four years of her life.

Tarbell’s success and celebrity were due, not so much to the impact and drama of her prose, but more so to her dogged dedication to truth and accuracy and to uncovering heretofore undiscovered information and sources that led to deeper and richer stories. Liza Mundy, writing in the Atlantic, observed that “a half century before the New Yorker’s Joseph Mitchell went to the waterfront to write about clammers and fishermen, before John McPhee started hanging out with greengrocers, Tarbell was visiting out-of-the-way sectors and practicing immersive journalism…. Today,” Mundy concluded, “Robert Caro is lionized for his exhaustive gumshoe method, but Tarbell was there before him, reading pamphlets and the opinion columns of local papers. ‘There is nothing about which everything has been done and said’ became her core insight.”

Even after Tarbell and the work of the stunt girls had produced such serious and game-changing work, it remained a struggle for women to be considered equals in the journalistic world. Even when they succeeded, broke through the barriers, their work was often discounted or ignored. As it was for Martha Gellhorn, who was on the scene in Madrid in the heat of the Spanish Civil War.

Here’s the opening of a dispatch from Madrid filed by Gellhorn in July 1937, which appeared in Collier’s magazine:

At first the shells went over: you could hear the thud as they left the Fascists’ guns, a sort of groaning cough; then you heard them fluttering toward you. As they came closer the sound went faster and straighter and sharper and then, very fast, you heard the great booming noise when they hit.

But now, for I don’t know how long—because time didn’t mean much—they had been hitting on the street in front of the hotel, and on the corner, and to the left in the side street. When the shells hit that close, it was a different sound. The shells whistled toward you—it was as if they whirled at you—faster than you could imagine speed, and, spinning that way, they whined: the whine rose higher and quicker and was a close scream—and then they hit and it was like granite thunder. There wasn’t anything to do, or anywhere to go: you could only wait. But waiting alone in a room that got dustier as the powdered cobblestones of the street floated into it was pretty bad.

I went downstairs into the lobby, practicing on the way how to breathe. You couldn’t help breathing strangely, just taking the air into your throat and not being able to inhale it.

Later, despite her accomplishments, Gellhorn had to fight or trick her way into reporting on World War II. Women journalists could not be trusted to report the news accurately, or so it was believed, and they were much too vulnerable to be let loose in a war zone like their male colleagues. But Gellhorn ignored the warnings and the arbitrary rules excluding women. She was one of the very few correspondents to make it ashore during the D-Day invasion, male or female. She did this by hiding in a bathroom of a hospital ship to be part of the landing, and once ashore disguised herself as an orderly, carrying a stretcher. She was discovered on the beach a few days later while conducting interviews with the soldiers who had safely landed, and she was stripped of her press credentials. She was not, however, deterred. A year later she was part of the first wave of reporters at the Dachau concentration camp when it was liberated.

I think it is really terrific every time I pass through the Pittsburgh airport that Nellie Bly has been so deservedly honored, side by side with Franco and George, but I do wonder if travelers really understand the significance of her statue and what it should mean to them and the world—not only the amazing trip around the world in seventy-two days, but the beginning of the liberation of women from a bastion of white men who had demeaned and disregarded them simply because of their gender. This liberation, would, however, not be quick or easy.

__________________________________

From The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting: How a Bunch of Rabble-Rousers, Outsiders, and Ne’er-Do-Wells Concocted Creative Nonfiction by Lee Gutkind. Copyright © 2024. Published by Yale University Press. Reproduced by permission.