How Motherhood Gave Me My Voice

Kate Rope on Getting Through Postpartum Anxiety

My grandfather gave me a subscription to The New Yorker while I was in college. He harbored a hope I might someday become a broadcast journalist and wanted to keep me abreast of current events, I guess. So, he wrote me periodically from his farm in rural Vermont, asking my opinion of particular articles.

But, I was in college. I did enough reading. Instead, I stacked the issues in the bathroom of my off-campus house in Los Angeles and read the cartoons on the toilet. The ones I liked I posted on the refrigerator, just like my grandparents did on their farmhouse fridge, 2,000 miles away. And then I returned his letters belatedly so he wouldn’t notice when I ignored his questions.

I received his last postcard the year after I graduated. As always, he asked about three articles I had not read. As always, I postponed my response. And, before I could send it, he suffered a stroke. Calling him in the hospital, I fessed up to the fact that I owed him a letter. “Yes. . . you. . . do,” he replied in a slow, slurry voice. That was the last time I spoke with him.

I flew back east for his memorial service, and—in the white church overlooking the town green—I delivered a eulogy in the form of the letter I owed him. Then I returned to LA and began a guilt-ridden campaign to read all my New Yorkers cover to cover on the commuter train home from work as a paralegal at Ernst & Young.

There I handled internal sexual harassment investigations and thought about going to law school. But I quickly realized I was uncomfortable representing one side of an issue. Sitting in conference rooms interrogating the men (they were all men), I felt an unexpected empathy for their flawed humanity. I saw their struggles too—and the collateral damage their behavior wreaked, not just on their victims, but on their families. I believed there should be consequences for what they had done. I just wasn’t comfortable meting them out.

Three weeks into my New Yorker binge, I realized that journalists shed light on all sides of an issue, presenting the harder, uglier parts of life with greater understanding—rather than punishment—to influence human behavior and policy. That felt better to me. I remember being halfway through a feature on mad cow disease—in which I was learning about agriculture, trade policy, neuroscience, and meat rendering—pausing to look out the train window at the palm trees flying by and deciding, “I want to be a writer.”

Within two months, I had applied for—and received—an internship at Mother Jones and moved to San Francisco to join a crew of scrappy, barely-paid interns getting schooled in the world of investigative reporting. But, I still felt out of place. I didn’t want to unearth dirt on people, elbow my way into the favor of hard-nosed editors, or make calls on what was right and what was wrong.

“And I found that I had stumbled—bleary-eyed and sleep deprived—into my purpose as a writer: to share the story of struggle. To let others know they are not alone, that there is a way forward when they just want out.”

I felt kind of like the girl in one of the New Yorker cartoons I posted on my refrigerator. Sitting in a window seat, she wrote a letter to her parents that began, “Dear Mom and Dad, thanks for the happy childhood. You destroyed any chance I had of becoming a writer.”

I had nothing to say.

Instead, I worked my way up the mastheads of magazines running research departments, waiting for inspiration, and watching the careers of my peers take off. And I turned my attention to becoming the only thing I had always wanted to be when I grew up: a mom.

The night my first daughter was born was the best night of my entire life. Holding her small, warm body against mine felt like inhabiting my destiny. Immediately, motherhood filled me with a purpose and direction that journalism had not. I kept working, but I cared less and less about the bylines of my colleagues and my lack of drive to match them.

And then, just when I was content to let ambition take a backseat to motherhood, motherhood gave birth to my career.

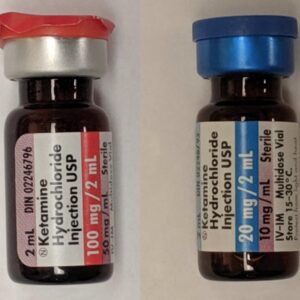

One week into my pregnancy with my first daughter, a mysterious and crippling pain gripped my heart, mystifying doctors and necessitating emergency CT-scans, chest x-rays, even a test in which a radioactive nucleotide was shot into my veins behind a thick metal door with a fallout shelter sign on it. I signed document after document that said, in a nutshell, the experts had no idea if what they were doing could hurt my baby but they needed to make sure I wasn’t about to die.

I went in and out of ERs and scanning machines for five months until a simple ultrasound of my heart revealed that the thin sac around it—my pericardium—was swollen with fluid. Every time my heart beat, it pushed into that little swollen sac, feeling like a blunt dagger to my heart. The condition—pericarditis—is actually a harmless, albeit extremely painful, condition, but it is often a symptom of autoimmune conditions. So, the remainder of my pregnancy was filled with other tests—for Lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia. I pounded steroids like a bodybuilder to keep the inflammation at bay and got weekly ultrasounds to make sure the ‘roids weren’t keeping my daughter from growing. I worried daily that my daughter would not be born healthy. And that I was very sick.

When she made her entry into the world—by all accounts healthy—I began a months-long descent into postpartum anxiety during which I was convinced that medical catastrophe loomed for her—and me. I couldn’t sleep. I vomited before work. I bullied an impressionable dermatology resident into biopsying my skin to look for lupus, when all I had was a rash. To this day, there is a chunk missing from my left arm, a tiny, daily reminder of the time I lost my damn mind.

I became such an intense germaphobe that I landed a first-person feature in Shape magazine for which I was photographed in a full-body yellow Hazmat suit in Times Square. Standing there—like a walk-on in the movie Contagion—fogging up the plastic face plate with my loud breathing, as tourists silently streamed by, was the perfect metaphor for the claustrophobic, paranoid, isolation that had become my life.

But I escaped from it with the help of a reproductive psychiatrist, 75 milligrams of the antidepressant sertraline, and weekly sessions with a fantastic therapist. And, surprisingly swiftly, I found myself back on the shores of motherhood as I imagined it—hard, but not petrifying, exhausting, but not perilously so.

And, finally, I had a story to tell. I sold that story—one of the first to bring postpartum anxiety into the open—to the trendy parenting magazine Cookie. That article led to others and to my first book deal. And in the midst of it, I decided to go for kid number two. This time, the panic slammed into me the moment I pushed her into the world. But I knew how to handle it, and my recovery came faster and easier.

So did my words. Not long after she was born, I was recruited to be editorial director of a reproductive mental health nonprofit. I began writing, assigning, and editing stories about the emotional impact of miscarriage, stillbirth, infertility, perinatal mood and anxiety disorders—the struggles so many face but no one talks about.

And I found that I had stumbled—bleary-eyed and sleep deprived—into my purpose as a writer: to share the story of struggle. To let others know they are not alone, that there is a way forward when they just want out. And from purpose and personal experience flowed my voice—open, nonjudgmental, brutally honest, occasionally funny. It started to resonate.

I began to hear from women that something I wrote gave them hope, made them realize they were not “crazy,” prompted them to call that therapist, talk to that friend, tell their partner, find a psychiatrist, look for a way to feel better.

This is the kind of advocacy I can get behind. This is my calling.

And I owe a debt of gratitude for it. First to a taciturn old man who showed his faith in me by sharing the written word. And second to my two daughters and the messy and transformative journey to motherhood that showed me that anything worth it’s life-changing salt doesn’t come easy and that it is not only ok, it is beautiful.

Kate Rope

Kate Rope is editorial director of the Seleni Institute and an award-winning freelance journalist whose work has appeared in many publications and online outlets including the New York Times, Real Simple, CNN.com, Shape, Glamour UK, BabyCenter, Parade and Parenting. She has been a key staff member of many national and international publications, including LIFE and Mother Jones and was a founding editor of Health.com. She is the author of Strong as a Mother and coauthor of the Complete Guide to Medications During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. She lives in Atlanta with her husband and two daughters.