How Mean Girls Taught Me to Fear Lesbians and Love Pink

Grace Perry on Her High School Years, Catholicism, and the 2004 Teen Classic

“Going into freshman year, I half expected high school to be like Mean Girls,” I told a church full of my classmates and their families. It got a laugh. Tina Fey’s high school comedy had come out four years earlier, at the end of eighth grade. And even then, in May of my senior year of high school, the movie had years to go before it became a classic, and before “Mean Girls day” jokes each October 3rd would strip the film of any cool factor. It was a just niche enough pop culture reference. I nailed it.

I was giving a speech at our Baccalaureate Mass, a senior class service on the eve of our high school graduation. This exact moment was the peak of my personal Catholic faith; it would all cascade downhill from here. I’d just completed four years at a Jesuit high school. The head of the Department of Formation and Ministry—we called it FAM (and, I regret to report, we called its regular participants the FAM fam)—asked me to give a speech reflecting on my time in high school in the context of my faith. I talked about “getting to know my true self and getting to know God,” and being “fortunate enough to be called to lead Kairos,” and “praying and reflecting on my service work.”

Our school’s church was so ugly, we called it Catholic Disneyland: life-size statues of the Saints peered down at parishioners, their robes painted vibrant blues and pastel pinks, their complexions distinctly European. Behind the altar, big, bright, exposed light bulbs dotted the apse as if it were a vanity, making the parishioners Judy Garland prepping for our close-up and Jesus our sleazeball manager, alternately feeding us speed and sleeping pills. Pontificating from the pulpit, I was the very closeted poster girl for Jesuit education.

*

I saw Mean Girls in a packed movie theater. My friend Nora and I went to the Biograph on Lincoln Avenue, back when the Biograph still screened movies. We walked back to my house, cackling and quoting the Plastics, and then we immediately watched Lindsay Lohan host Saturday Night Live. That episode—May 1, 2004—was best known for the inaugural “Debbie Downer” sketch, though I best recall the one where Lohan plays Hermione Granger with gigantic boobs. (Hm.) As Nora and I shrieked with laughter in my basement, I knew I’d fallen in love with Mean Girls and perhaps with Lohan, too.

I liked the cadence of the jokes in Mean Girls: the surprising lyricism of the phrase “heavy flow and a wide-set vagina”; the way, as Karen Smith yearns to mack on her cousin, “Seth Mosakowski” rolls off her tongue; the uniquely high school catchiness of the words “the projection room above the auditorium.” It has a unique tempo, marked by a tender heart interwoven with gentle digs at the genre. (“You know, it’s not really required of you to make a speech,” Tim Meadows’s Principal Duvall interjects during Cady’s sentimental spring fling address.)

When I watch Mean Girls now, it’s like revisiting an old album I’ve worn to death, scratches be damned. I get chills with the honeyed way Regina asks the newest Plastic, “Cady, will you please tell Aaron his hair looks sexy pushed back?” and in her equally evil but cool, “Because that vest was disgusting!” The humor sounds like music to me.

Mean Girls made me feel seen and my insecurities understood. In the content, yes, but mostly in Fey’s writing, which treated teenagers how they really are: smarter than they look. Mean Girls doesn’t talk down to kids, neither in how it treats teen girl drama (as genuinely hurtful and lasting) nor its jokes. It hit me right at the perfect age, 14: I’d had enough health class to know chlamydia doesn’t start with a K yet lacked the life experience to have any idea what “butter your muffin” means. I was familiar with the cringey trope of cool moms, sure, but I had to laugh along with “What are marijuana pills?” to not look like an absolute dweeb. The jokes felt a step out of my age bracket, and I loved that challenge—nothing makes a joke funnier than getting it despite it being intended for someone smarter than you, nor more satisfying than that smugness. It was the humor, more than the story itself, that made Mean Girls feel so personal to me.

Before I knew what a personal brand was (I still don’t, really), Mean Girls was my personal brand.

After that first viewing with Nora, I wanted Mean Girls injected into my veins and got as close as I could without getting blood poisoning. Two weeks after seeing it, my eighth-grade class went on a trip to New York. We saw the Lower East Side Tenement Museum and the Statue of Liberty and Hairspray with Michael McKean as Edna. But what sticks out most in my mind were the two hours our teachers just let us cut loose (?) in Chinatown (??) to buy a bunch of bootleg crap (???).

I bought a DVD recording of Mean Girls someone had taken from the back of a movie theater with a handheld camcorder. It wobbled and flickered, the sound grainy and distant like it was playing from the end of a very long hallway. (I also bought a similar DVD of Troy, which is the first and last time I’ll be mentioning Troy in this book, despite its flagrant homoeroticism.) I watched that bootleg recording on my pink desktop iMac nearly every day of that summer; by the time freshman year began, I knew it word for word. Not because I actually thought it was an accurate depiction of high school—I lied in that baccalaureate speech to get the laugh, sorry—but because I felt the jokes respected me. Before I knew what a personal brand was (I still don’t, really), Mean Girls was my personal brand. The jokes were smart and funny, and my loving them meant that I was smart and funny, too. It became part of my identity.

Despite an obscene number of Mean Girls viewings, only as an adult did I register the movie’s most brutal insult is a homophobic one: “Janis Ian—Dyke.” It’s written in the Burn Book and photocopied for the whole school to see. The big offensive thing here, in the world of Mean Girls, isn’t that the Plastics use a gay slur. The mean thing the Plastics do is call Janis a lesbian. It’s more than that, though. In eighth grade, Regina started a rumor that Janis was gay, which ostracized Janis at school and prompted the end of their friendship.

“I couldn’t invite her to a pool party! There were going to be girls there in their bathing suits,” Regina says, explaining the roots of their years-old feud. “I mean, right? She was a lesbian.”

It’s posited as a reasonable prompt for Janis’s unbridled hatred of Regina and is even perceived as degrading to “too gay to function” Damien. When Cady takes a page out of Regina’s book and accuses Janis of being in love with her, he slams on the brakes and urgently defends his friend—“Oh no, she did not!”—knowing Cady had just cut Janis where it hurt most. In Mean Girls, calling someone a lesbian is treated as an insult unto itself; it’s the worst version of “grotsky little byotch.” It’s simply an insult, a bad insult, an insult cruel enough to tear up a friendship, to incite a year-long revenge plot and a burning urge to fully destroy the girl who made that claim.

No one likes to be misrepresented, sure. But the fact that being called a lesbian is an insult is, well, pretty insulting to lesbians. One could argue the movie isn’t trying to be homophobic, that Regina’s the homophobic one, that the writing mimics the casual homophobia teens used in the mid-aughts. And, yes, it would be natural for self-conscious teen girls to revolt at being called a lesbian—I know I did. And all that might be true. But the writing certainly doesn’t stick up for queer women, either. Despite Janis wearing a purple tux to Spring Fling, Fey is sure to disprove Regina’s allegation in the final scene, as Janis makes out with Kevin G. in pure, blissed-out heterosexuality.

After upward of 75 viewings of Mean Girls 2004, I internalized the idea that, like Regina argued, lesbians shouldn’t be allowed to go to pool parties with straight girls. I worshipped the movie—and Fey, too. And so, a subtle but disappointed narrative nestled into a corner of my brain for years after 2004: it’s cool for guys to be gay. It’s cool for girls to be friends with gay guys. But it’s an insult to be called a lesbian. Or, as Liz Lemon puts it in a 30 Rock episode, “My boyfriend and I aren’t married, but we might have a baby together anyway. And I hope it’s gay! Male gay. Because with the ladies, it’s too much hiking.” To be fair, that’s not untrue.

*

My high school experience wasn’t like Cady Heron’s for a whole host of reasons, ranging from “I wasn’t a homeschooled jungle freak” to “no boys wanted to have sex with me.” But, especially, there was the whole Catholic thing. To answer your first questions, no, my school wasn’t single-sex, and no, we didn’t wear uniforms. We instead stuck to a dress code that insisted we look like the assholes in every 80s movie: collared shirts, no jeans, knee-length skirts. (My friend Anne so relentlessly abused the mid-aughts pleated mini-skirt trend that I believe she single-handedly inspired the school’s skirt minimum length to be extended from mid-thigh to knee. Brava to Anne.)

Defying the dress code would earn one a Jesuit school detention called a JUG, which stands for Justice Under God, something so on the nose, it’s not even worth unpacking. But the most Catholic thing about Catholic school—including crucifixes in every classroom and all-school masses and praying as a team before cross-country races—were our required religion classes. In 2007, while Lindsay Lohan began her famous will-they-won’t-they dance with rehab, I was taking my junior year Catholic ethics class with my religion teacher, Mr. Baird.

Mr. Baird was a Texan Marine turned high school religion teacher, a broad-shouldered action figure of a man. He looked like a redheaded Jesse Plemons—so much that, a decade after I left high school, my father would watch The Post and remark on the talent of “that guy who looks like Mr. Baird.” In class he was abundant with energy, nimble even, which I guessed was a holdover from his morning commute up Lake Shore Drive on a recumbent bike. He was a passionate educator, who firmly believed in hard-assedness as a means of teaching hard lessons.

The fact that being called a lesbian is an insult is, well, pretty insulting to lesbians.

Mr. Baird appeared to delight in rules and was ruthless in giving JUGs; I had to wear socks with my (heinous) Birkenstock clogs every damn day of junior year. Despite the demons the veteran undoubtedly wrestled on those low-to-the-ground bike rides, he was warm, and funny, and alluring, and spoke with such passion on just about every subject that his words always wiggled into my brain and nestled into its folds. If you asked me at my Baccalaureate Mass, I’d tell you I’d learned more from his class than any other in high school.

Mr. Baird’s Catholic ethics class was my first introduction to philosophy. Catholic dogma is more based on philosophy than it is on the Bible—a call to return to the text itself was the whole point of the Protestant Reformation, after all. And Mr. Baird seemed to relish Catholic thinkers’ place in the larger tradition of Western philosophy. And in order to understand contemporary Catholic teaching, Mr. Baird insisted, we needed to read Catholic philosophers like St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and C.S. Lewis. And understanding those thinkers required conversational fluidity in Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, and even Kant, Freud, and Marx. We had pop quizzes on our dense reading assignments several days a week. His class was hard, and he expected us to rise to the text. Like Tina Fey, he treated our minds as adult ones, and I liked that.

We spent the first semester pretty much exclusively reading and discussing Plato and St. Augustine of Hippo, whose philosophies, Mr. Baird was delighted to present, were parallel. St. Augustine’s whole thing was that Original Sin has made us all terrible messes, and we should do all we can do to free ourselves of our bodies’ desires and be closer to God. Fair enough.

We read excerpts of St. Augustine’s Confessions (400 AD) just two years after Usher’s album of the same title was released. In what’s basically a memoir, Augustine writes as a fortysomething about his teens, twenties, and thirties, the sins that paved his way to eventual Christian conversion. It’s heralded as both the earliest autobiography and a cornerstone Catholic text and is essentially a magnum opus on how desperately the 5th-century North African thinker wanted to bone.

Before getting to sex, Auggie kicks things off with a story of teenage folly. As a 16-year-old, he and his buddies stole a bunch of pears from a nearby orchard, despite having plenty of pears of their own. They ate a couple then gave the rest of the pears to some pigs, apparently delighting in the sheer fun of stealing shit when you’re a bored teenager. Augustine uses this as proof of Original Sin. Okay.

Post–pear incident, St. Augustine’s main thing is: he’s horny. He spends most of his twenties banging an unnamed woman (exclusively, he does note), and though they’re not married, they have a son together. When he’s 29, his mom, St. Monica, sets Augustine up with another woman to wed. He breaks up with his baby momma and then finds another woman with whom to cheat on his new wife. Come on.

Looking back as a Christian 40-year-old, Augustine describes this as the worst time of his life. He writes, “I had been extremely miserable in adolescence, miserable from its very on-set.” He’s really, really hard on himself for having been a twentysomething with a sex drive. Augustine isn’t really concerned about the women he’s cheating on; rather, he ruminates strictly on his personal moral failings and how giving in to his urge to sin only widened his well of unhappiness. Sex, he says, drew him further from God. In that time, youthful and captive to the wants of his schlong, he prays, “Grant me chastity and self-control, but please not yet.” Which is extremely funny, as it essentially translates to, “I’ll stop masturbating to my memory of a crumbling bust of Venus . . . uh, tomorrow, I swear.”

He became all the proof I needed that converts are always the most intense religious types.

Eventually, St. Ambrose helps him convert to Christianity. The rest of Confessions consists of prayers, spiritual meditations on human nature, and general disdain for being a human being trapped in a human body with human needs. At the time, it was written as a how-to guide for early Christian converts, a sort of Early Christianity for Dummies. Mr. Baird felt about St. Augustine the way St. Augustine felt about cheating on his wife: simply addicted. My teacher nearly drooled in hysteria the day he finally replaced the descriptors in Plato’s allegory of the cave (“cave,” “shadows,” “sun”) with language from Augustine’s Theory of Knowledge (“Original Sin,” “temptation,” “God”) on the chalkboard at the front of our classroom. I had a galaxy-brain moment then, too.

As my introduction to Western philosophy, Mr. Baird’s class was also my introduction to the malleability of philosophy to support otherwise arbitrary opinions. Based on what he discussed in class, his own Catholic ethics, suspiciously, matched Bush-era Republican talking points at the time (abortion bad, immigration bad, death penalty good, war good). My family was and remains Chicago Catholic: blue-voting descendants of Irish immigrants, loyally fueling the city’s iron-fisted Democratic Machine, for better or for worse.

Liberal Catholic may sound like an oxymoron, given the whole “abortion is evil” and “we loathe women” things, but given the sheer global expanse of Catholics, Pope-followers run the political spectrum, from liberation theologian Oscar Romero on the left to Pope Benedict XVI on the right. Mr. Baird was a different kind of Catholic than I’d known to that point. He did something even wilder than joining the armed services in wartime: he chose to be a Catholic. Mr. Baird converted from Anglicanism, which is basically just Catholicism, except women can be priests and people can divorce, after teaching Catholic ethics for years. Apparently he didn’t like ladies turning bread into Jesus, or the ending of marriages. He became all the proof I needed that converts are always the most intense religious types.

__________________________________

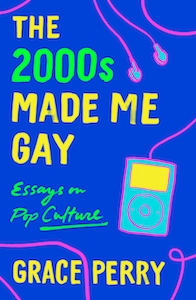

Excerpted from The 2000s Made Me Gay: Essays on Pop Culture. Reprinted by the permission of the publisher, St. Martin’s Publishing Group. Copyright © 2021 by Grace Perry.

Grace Perry

Grace Perry's work has been published in a variety of outlets, including The New Yorker, New York magazine’s The Cut, BuzzFeed, Outside, and Eater. She is also a longtime, regular contributor to The Onion and the feminist satire site Reductress. Most of her work, comedy and journalism alike, interrogates the intersection of queerness, pop culture and the internet. She lives in LA.