How Madame Mao Remade Hollywood For Chinese Audiences

Ying Zhu on Jiang Qing's Influence On Mid-Century Chinese Film

After decades of successful screening in China, Hollywood films vanished from the Chinese screen during the Mao era. Yet, hidden from the public eye, many Western films, including classic Hollywood films, were available to the party rank and file as well as to key film professionals. These became known as “internal reference films.”

The phenomenon of clandestine viewing of Hollywood films lasted until the end of the Mao era; watching poisonous films was a common ritual among the privileged few with access. The studio responsible for the translation of many such internal reference films was the Shanghai Dubbing Studio.

*

Despite the ban on Hollywood films early on, and on Soviet films later, foreign films became available through restrictive internal screening to film practitioners for professional needs and to an exclusive group of ranking party officials led by Mao Zedong’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing. A second-rate movie actress herself during the Republican era, Jiang Qing was a closeted Hollywood devotee with a trove of Hollywood films, mostly dubbed but some in original versions, at her private disposal, even when she was attacking Hollywood in public.

She reportedly had a fondness for classic Hollywood films of the 1940s, including Bathing Beauty (George Sidney, 1944), Jane Eyre (Robert Stevenson, 1943), and The Red Shoes (Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell, 1948), which were housed at the China Film Archive, a Beijing-based archive established in 1958 under the direct administration of the central government’s Department of Propaganda. Jiang told people around her that “the 1930s–40s was the period when capitalism was on the rise, so the films made during the time were more enjoyable.” She reportedly made Hollywood titles available for internal viewing so that ranking film professionals could learn advanced production techniques from Hollywood, never mind the “decadent” nature of Hollywood productions. A 1965 production plan issued by the Propaganda Department at the end of 1964 permitted the appropriation of Hollywood techniques in the production of socialist films.

These closed viewings at the same time helped Madame Mao reach decisions on what foreign films should be emulated.

Established on April 1, 1957, Shanghai Dubbing Studio was the successor to the Shanghai Studio’s Translation Unit led by Chen Xuyi, a veteran translator of English-language stage plays. The Translation Unit re-voiced exclusively Soviet films in 1950–52. Films from Eastern Europe were added to the list in 1952–53. Starting from 1954, efforts were made to introduce a diverse range of films from Asia, Africa, and Latin America as well as progressive titles from the West, including Western adaptations of world-renowned literary works and films of diverse styles and trends, many of which were world classics. The Translation Unit re-voiced several memorable films in the 1950s, including Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945), which was dubbed for public viewing in 1954.

Translation and dubbing originated in 1930s when France, Italy, Germany, and Spain started using local actors to re-record dialogue for imported American films. The process of replacing the original audio with translated voiceover is known as dubbing or “re-voicing.” Similar to creating translated subtitles, where literal translation is usually replaced with a translation that captures the basic meaning and intent of the original dialogue, the audio in dubbing must be translated into the local language and the sounds of words must match the shapes the actors on screen make with their mouths. The voice actors’ voice performance must also match the tone and rhythm of the original audio.

In the quintessential dubbing method called lip-sync dubbing, the original audio is completely removed, translated, and re-recorded in order to match the mouth movements with the local-language sounds. In China, the re-voicing pioneers knew little of this, and with no access to European practices they turned to the Soviets for techniques. But the quality of Soviet dubbing, as shown in Soviet films with Chinese re-voicing done by Russian actors, was not up to par, so the Shanghai team experimented with various methods on its own.

One advanced technique, known as “looping,” consisted of playing short pieces of the original dialogue over and over with a special machine until a proper audio recording was done. A less expensive way was lock-to-picture recording, where the voice actors just watched pieces of the film over and over and recorded their audio until it matched perfectly with the original performance.

The Shanghai team could not afford the expensive machinery needed for looping, so they had to make do with the more labor-intensive lock-to-picture recording. To ensure quality delivery, Chen Xuyi assigned each film a director to work with voice actors to rehearse and do multiple recording takes. The studio also obtained original scripts from overseas to do the translation before re-voicing.

In 1957, the Translation Unit’s office in the Hamilton Building (now Fuzhou Mansion) in Shanghai’s Jingan District became the base for the newly established Dubbing Studio. Headed by the same Chen Xuyi, the newly independent Dubbing Studio served at Madame Mao’s pleasure by translating and re-voicing foreign films on demand. The dubbed films were made available for internal viewing ostensibly to detect and ward off unhealthy cinematic undercurrents, but these closed viewings at the same time helped Madame Mao reach decisions on what foreign films should be emulated.

*

Between 1949 and the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, internal reference films were only accessible to party rank and file at Zhongnanhai, the exclusive party compound adjacent to the Forbidden City. Once a Qing imperial garden, the place has served as the central headquarters for the CCP and the State Council since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It houses the office of the president and premier of the PRC. Screenings of internal reference films frequently took place at the Western Hall of the compound, with the highest security clearance.

A special pass signed by Yang Shangkun, then director of the CCP Central Committee, was required to enter the Western Hall. Party leaders who frequented the internal reference film screenings included CCP secretary-general Deng Xiaoping and Liu Shaoqi, chairman of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee from 1954 to 1959; it was said that Liu and Deng were among the most devoted attendees at these private weekly screenings. Other attendees were the dancers who came to Zhongnanhai to serve as CCP leaders’ partners during the compound’s frequent ballroom dance parties.

Mao’s wife was keen to keep abreast of new cinematic trends around the world, and her personal taste dictated national choices.

Jiang Qing also held secret screenings of so-called “workshop films.” Mao’s wife was keen to keep abreast of new cinematic trends around the world, and her personal taste dictated national choices. Internal memos dispatched to production studios carried Jiang’s frequent instructions to the Chinese film community, ranging from making film prints green instead of red, which was more routinely used in Chinese production, and to use more “long takes” that were in vogue in both Hollywood and Soviet cinemas as well as European cinemas, which explained the stylistic choice of Chinese films made during the period, including Early Spring in February, which utilized long takes to capture the stillness of life in a small town.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, to improve Chinese filmmakers’ professional skills, internal reference films were organized at the building that housed the China Filmmakers’ Association in Beijing. The association showed films at its 200–300-seat screening room every Sunday, and many of the films screened were pass-throughs. Instead of returning to the distributors right away, Chen Huangmei, the deputy head of the Ministry of Culture, made these films available for “sneak previews” to filmmakers with little exposure to world cinema.

Some pass-through films, including political films from Eastern Europe, had no dubbing or subtitling and required on-site translation; in these cases, language experts were brought in for simultaneous translation. The association ran a snack bar at 4:30 p.m. every Sunday for people to gather and discuss films before the 6:30 p.m. screening. These weekly Sunday screenings and discussions essentially functioned as a salon for Western films. Titles screened were eclectic, ranging from Dracula (Terence Fisher, 1958) to Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959); many were award-winning or festival-nominated films.

During the early days of the Shanghai Dubbing Studio, the studio would screen internally the rough cut of its dubbed version before submitting the film to Jiang Qing’s people for approval. Studio staff could receive four complimentary tickets per week. That special viewing privilege brought esteem and conferred power. Family members of Shanghai Dubbing Studio staff used tickets to bribe schoolteachers, canteen servers, and food venders. Going to the Dubbing Studio to watch re-voiced films became a sought-after event. As Pan Zhen, the son of the renowned voice actress Liu Guangning, recounts, his family used tickets to exchange for meat and other food ration coupons.

Access to internal reference films actually widened during the Cultural Revolution, particularly for key film practitioners and cultural gatekeepers whom Madame Mao deemed essential to her effort to launch quality domestic revolutionary film production. The Proletarian Command Centre Jiang Qing set up in Beijing to facilitate the Cultural Revolution issued an order in 1970 for the Shanghai Dubbing Studio to re-voice eight films for internal circulation. Code-named “Shanghai Internal One to Eight,” the films included the French film The Red and the Black (Claude Autant-Lara, 1954), a co-produced film shot in Vienna titled Bel Ami (Louis Daquin, 1955), the British film The Red Shoes (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948), the Hollywood musical The Unfinished Dance (Henry Koster, 1947), and several British documentary films.

__________________________________

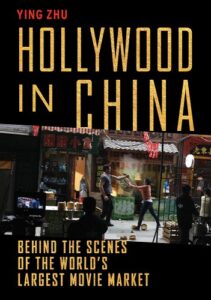

Excerpted from Hollywood in China: Behind the Scenes of the World’s Largest Movie Market by Ying Zhu. Copyright © 2022. Available from The New Press.

Ying Zhu

Ying Zhu is professor emeritus at the City University of New York and director of the Center for Film and Moving Image Research in the Academy of Film, Hong Kong Baptist University. The recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, she is the author of four books including Two Billion Eyes: The Story of China Central Television and Hollywood in China: Behind the Scenes of the World’s Largest Movie Market (both from The New Press) and co-editor of six books including Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: China’s Campaign for Hearts and Minds. She is the founder and chief editor of the peer-reviewed journal Global Storytelling: Journal of Digital and Moving Images. She resides in New York and Hong Kong.