How Living in Naples Changed Shirley Hazzard’s Life

“If you come to live there, come to know it, you will live in other times.”

Whenever Shirley Hazzard was asked about the definitive moments of her life, she spoke of going to Italy: “From the first day, everything changed. I was restored to life and power and thought.” Being in Italy returned her to a prior and loftier order of being, anterior to Australia and her unhappy family; with it “a whole part of my life that had been suppressed came back.” The significance was clear even at the time.

22 December 1956 Saturday, Naples

I am in Italy.

It is simply that one Friday, three weeks ago, I walked into Max Doerner’s office and asked if, because of the UN emergency missions in Naples and Cairo, they were looking for applicants. On Monday I was called, interviewed, accepted, and on Friday I left New York for Naples.

Her sense of the moment—the occasion—of Italy is plain in the rhythm of the sentences that follow the stark declaration of time and place: plain monosyllables give way to a sequence of dependent clauses and descriptive phrases separated by a string of commas, drawing us into the story. Also striking here is the locution she would later deploy in the opening paragraph of The Transit of Venus— “It was simply that . . .”—heralding the arrival of an apparently unimportant figure, an arrival that will set in play events of high drama: a novel. As she later observed of the opening of The Bay of Noon, set in Naples in the late 1950s, “There has been a break with previous experience; something new is beginning.”

In later accounts of this posting, highlighting its fortuitousness, she often spoke of herself as merely the beneficiary of decisions made elsewhere: “Entirely thanks to having studied Italian, I was precipitately sent on a year’s mission to Naples . . . This was a time of crisis in my private as well as my working life, and the assignment came as if by divine intervention—the first of a series of miraculous reprieves that transformed my life.”

Yet her diary entry, the last for 1956, makes clear that it was she who requested the posting in order to leave the TAA office, which had become unbearable to her after the break with Tex Goldschmidt. While this doesn’t play as nicely into the story of miraculous rescue, it does signal a shift in the story of her own self. From the tearstained, passive despair of the preceding months, immobilised by Tex’s rejection, she responded with action, making a move, taking charge—taking care—of herself.

She would find that much was difficult, but as time went on, her sense of the rightness of this move, to leave New York and embrace the unknownness of Italy, only became more evident. In part this was a function or consequence of Italy itself; she came to look back on those early winter months there as “realistic and clear and somehow enclosed.” But more than that, she began to be aware of the importance of moving away from known worlds, the importance of movement itself. This would later become a touchstone for her larger thinking about life, her mobile protagonists and their shifting worlds. The other defining coordinate was loneliness, a quality to which she returned when thinking back over these years:

The traveller equipped with even one introduction arrives with a card to play, a possible clue to the mystery. Yet those who have never experienced solitude in a strange and complex place— never arrived in the unknown without credentials, without introductions to the right people, or the wrong ones—have missed an exigent luxury. Never to have made the lonely walk along the Seine or Lungarno, or passed those austere evenings on which all the world but oneself has destination and companion, is perhaps never to have felt the full presence of the unfamiliar. It is thus one achieves a slow, indelible intimacy with place, learning to match its moods with one’s own. At such times it is as if a destination had awaited us with nearly human expectation and with an exquisite blend of receptivity and detachment. The moment comes: we intersect a history, a long existence, offering our fresh discovery as regeneration.

In these lines there is a sense of wonder at her own great good fortune. There is humility and also a grasp of the immensity of experience to which she had access, the privilege of travel, particularly in those postwar years. Perhaps she is paying tribute to those occasions when she speaks of them as having arisen through miraculous intervention rather than her own agency. She was still caught up in the long process of severing relations with her family and her place of birth and had not yet made a home for herself anywhere else. But the profound connection felt with Italy, the intimacy developed with its “long existence,” provided a starting point for cure.

“When I entered that city I knew that it was a coup de foudre.”

She left New York on December 7, 1956, “a frigid night,” on a Pan Am flight from Idlewild. She was twenty-five years old. Her arrival in Naples on a bright winter morning was solitary, and this solitude largely defined the months she spent there. She was often resentful at Tex’s abandonment: “I came here alone, knowing no one—he let me go to the other side of the world to be alone, with no word, no message, and I have had a hard, hard nine months.”

Her appointment was for a year, working for the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) in an office that had been established at Naples airport to assemble and fly supplies to the peacekeeping forces at Suez. She was lodged at first with senior colleagues in central Naples, in the Hotel Vesuvio, “one of the good hotels on the seafront,” on Via Partenope, looking out on the bay.

She marked the window of her room in the Vesuvio in a postcard to Valerie, noting that across the street were “restaurants, and a pier leading out to an ancient fortress on a tiny island—the picture doesn’t do anything like justice.” The fortress was the twelfth-century Castel dell’Ovo, “a medieval construction in blonde stone rising on a fragmentary villa of Lucullus,” where, according to legend, the siren Partenope washed ashore after failing to seduce Ulysses with her song, and where later the poet Virgil buried an egg, warning that should the egg break, the castle and city would also fall.

If her location was mythic, her daily life was rather less so. Six, sometimes seven, mornings a week she and her colleagues were collected by the office “vehicle” and driven an hour or so to the UNEF at the “shattered” airport and then returned to their hotels in the evening. In the office she was again assigned routine secretarial work, mainly typing, work enlivened only by the fact of being transacted partly in Italian. Despite her—at that stage—rudimentary grasp of the language, she had the responsibility of dealing with visitors and phone calls in Italian, as the military officers could not speak the language at all.

She shared the office with two young women, one of them Suzanne Puffet from Brussels, with whom she quickly became friendly. She also established a lasting friendship with Lily Aprile (later Gravino), a Neapolitan local who was also working there as a typist. Lily recalled Shirley as overwhelmingly sad that year, consumed by her recent heartbreak. Shirley’s boss was a New Zealander, Major A. W. Cooper, whom Lily remembered as a “typical military man”; perhaps he was one of the unappealing types Jenny encounters at the NATO office in The Bay of Noon—“perpetually seething—with fury, with fear, and with the daily necessity of striking out before they could be felled by inapprehensible foes.”

There was no consolation to be found in congenial colleagues. Apart from Lily and Suzy, Shirley found herself isolated.

Trapped with a handful of stupid, grudging, coarse people in a wretched, time-consuming office that has a nightmare quality about it. I have longed, longed for the companionship of my office in New York . . . I’ve spoken of my interests to no one all this long time—on one or two occasions at the beginning I tried and was put in my place as someone who wanted to impress their intellectual superiority on others. Oh dear dear God, how I have hungered for one of those dear conversations with Luker, for a talk with someone whose knowledge and understanding and humour is responsive to my own. Trapped between the 8–5pm, seven or at least six days a week at the office, and the inadequate knowledge of the language, I have known real loneliness.

In New York, she was missed, too, as Norman Luker wrote her just before the end of the year:

Your absence is palpable—I always seem to be hearing something in the elevator or reading something or occasionally even thinking something that it would have been pleasant to mention to you (had you been here I might have commented on getting the mimeographed paper on the Christmas party announcing that “invitations were to be on a restricted basis” that it appeared to be an occasion when we were letting joy be confined). I can of course pay the tribute of a sigh to my contributions to such unheld conversations but yours are a total loss.

Howard and Judith came to Naples in early 1957, but visits could be no substitute for more local and daily friendships. Howard later wrote her an enraging letter that she likened to Alec d’Urberville’s preaching to Tess, noting it as a possible scene for a novel: “She held a letter and reflected that she was not the first woman to receive a homily from/by her seducer.”

Her fellow workers at the UNEF were not only not simpatici, they also failed to embrace the life of the city around them. There were the English girls—“Angelas and Hilarys and Rosemarys who had wanted to get away from Reading or Ruislup or Holland Park,” over whom “hung an immanence, a pale expectancy, as if their youth had not yet come to them.” And the other expats, who were living out “their term of exile, requiring nothing of Italy or its language, passing among themselves stale, trumpery talismans of home, recreating a former existence from the shelves of the PX until such time as they should—on other, equally alien shores—speak with nostalgia and authority of the Bay of Naples.”

But she was not just critical of the expats, or of her colleagues, the military men “who lived among men” and were “afraid of women.” In an early fictional account of expat life, “A Sense of Mission,” she would find comedy in the hapless romanticism of her protagonist’s response to the city, most likely informed by her own. Clelia Kingslake thrills to have arrived in Rhodes and is “revisited by ecstasy” at the “glimpse of golden walls, of white shipping, of a tower, a fortress.”

On her first morning there, when Miss Kingslake hears on waking “the rhythmic crunching of waves up the pebbled shore,” she murmurs to herself lines she had memorised, “Sophocles long ago heard it on the Aegean,” and feels herself to be “in however modest a degree, the instrument of a great cause: in this setting redolent of antiquity she even risked to herself the word ‘handmaiden.’” But this light mockery is counterweighted by the baser failures of Miss Kingslake’s colleagues, who substitute their own interests for those of the organization they represent and for whom the only “Mysteries” to be found in the ancient city are heard in the aggressive Signor Grilli’s rapid and sycophantic pronunciation of the name of the head of the local logistics division, “Mr Rees.”

“There are accretions, layerings like seabeds. One enters strangeness . . . If you come to live there, come to know it, you will live in other times.”

That year, she lived with an awareness of the weight and significance Naples would come to have for her life. The city was unlike any place she had encountered, “a blitzed town of large-eyed, overburdened, resilient people. Many of its great churches and palaces lay open to the elements; its waterfront was a shambles.” As well as the massive bombardment of war, itself compounded by the eruption of Vesuvius in 1944, Naples had continued to suffer from “recent ravages of dictatorship and conquest,” and consequently failed to attract foreigners. She felt herself to be one of a privileged few who were there then, one of “those who came to know Naples in that era” and “would feel attachment to it all their lives.”

Looking back, she had no doubt of its promise: “The city was the thing that was important to me and the region and being in Italy. Like going to the East it was a tremendous change in my life.” She also found, retrospectively, premonitions of its significance, fancying Vesuvius, the “great dictatorial god” of the city, as having been prefigured in her first sighting on sailing into the Mediterranean half a decade earlier, of the volcano Stromboli, the “first outcropping of Europe.” Although she left little tangible record of this time—no diary, just a handful of notes and few surviving letters—she did provide extended descriptions of the city for many years afterward, most of all in her 1970 novel The Bay of Noon, which she described as “a love letter to Naples.”

Like her protagonist Jenny, in those first weeks she was herself waiting “for the city and its intervention,” waiting to step out from the office into life. As Jenny’s friend Gianni (himself another outsider, from Rome) tells her, “‘It’s the city, the phenomenon of Naples itself, that knows something. It’s like an important picture, or a book—once you’ve taken it in, you can’t believe there was a time when you didn’t know it.’ He turned to me. ‘This will change everything for you, being here. Naples is a leap. It’s through the looking-glass.’ And I looked out at the oval mirror of the bay.” The promise here is for insight, but it is a perspective to be acquired only gradually: “It was necessary to live there rather than visit it to have a feeling of this great quality.” That “feeling” for Naples would cohere in the shock of the city’s embrace. For a young woman who had felt unhoused in the city of her birth, this was “a revelation . . . like going to heaven.” Naples was “desperately poor,” and yet:

When I entered that city I knew that it was a coup de foudre. I knew that this was where I wanted to be. Bit by bit I began to have this great companion, the city of Naples, and of course to learn all sorts of things there—to change my way of looking at things, to enlarge my way of looking at things. The year passed with as much interior development in me as the previous four or five years and perhaps even more. For one thing, I became joyful . . . really for the first time I knew what joy was. It became a part of my life, I understood at last what that was. I saw life even in the midst of so much difficulty and suffering. It had vitality, there was blood in the veins and it was quite a different life from the life I’d been accepting and had even begun teaching myself to accept as a necessary and rightful thing.

The walk taken by Jenny early in The Bay of Noon carries the imprint of Shirley’s own passage through the city; it is a walk she commends to her readers in a 1982 essay on Naples—from the waterfront hotels to Spaccanapoli, “where the city ‘splits’ along its Greco-Roman axis, to the Gesù Nuovo.” Jenny walks up “a ramp of a street that rises to a corner where Degas once lived with his Neapolitan relatives.

The ascent, oblique, suggests the piazza above it by giving, as if through a door ajar on a high landing, a glimpse of the exorbitant, gem-cut façade of a church, with to the left a flash of red stucco, to the right an ornate obelisk.” She crosses the piazza to “the faceted stones of the church. From there one looked, then, across at the bombed shell of Santa Chiara, half-reconstructed, and at a derelict campanile on the one hand and a massive palace on the other; and this I did for some moments, only showing it was new to me by enquiring, of the priest who came to close the church, the way to San Biagio dei Librai.”

Striking in these passages is the sense of arrival, of encounter. If the evocations of Middle Harbour at Sydney conjured a nascent sense of literature, the possibility of being a poet, and if the vistas of Hong Kong opened out the topography of the global world, then Naples was a site of self-discovery, “through the looking-glass,” offering inward as well as outward prospect. There is also the animation of the scene, the liveliness that sits in sharp contrast to Jenny’s own quiet isolation, a liveliness that yet welcomes her.

Shirley, too, was welcomed into friendship there, the acquaintance with Lily Aprile developing in the months and years that followed to become one of the great constants of her life. Perhaps it was with Lily that she had coffee that winter, “standing up at a counter . . . fierce black coffee, a spoonful apiece, served in tiny cold cups that were always wet from the draining board,” or shopping for a Christmas tree for her boss, “giggling all the way like schoolgirls and wiping away tears of joy.”

What Shirley saw in the city’s vistas encapsulated and defined her own experience, her sensations and her emotions, becoming a kind of visual shorthand:

When I think of that time, the thoughts and feelings we all had, I feel—oh, as one does when one sees on the slopes of the Vesuvius or up above Sorrento one of those old-fashioned, cream-coloured hotels standing almost empty with all their old furniture that no one values, their décor that only depresses, the two or three elderly guests, speaking low so as not to disturb by giving a sign of life.

She reflected often on the city’s qualities of ancientness: “There are accretions, layerings like seabeds. One enters strangeness . . . If you come to live there, come to know it, you will live in other times.” As she began drafting The Bay of Noon, she reflected on the complex sense of time that the city engendered for her:

It is the oddest thing to me as I write this story, to remind myself of my present age which though mature, is by no means advanced, and of the actual distance between me and the events I am now recalling, which is only eleven years. The expression “That seems like another existence” would not do to describe the distinctiveness of that time from my present life, for it is the present life that seems like another existence . . .

This passage from her notebook is more than likely a draft for one of Jenny’s reflections than a diary entry (it is not always possible to distinguish between the two) and speaks to the complex and layered reflexivity that would come to be one of her defining writerly traits. In this it suggests how central was the experience of Naples to her coming to writing.

__________________________________

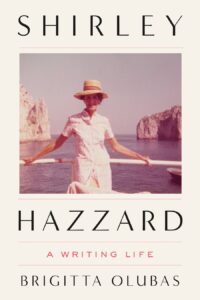

Excerpted from Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life by Brigitta Olubas. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, November 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Brigitta Olubas. All rights reserved.

Brigitta Olubas

Brigitta Olubas is a professor of English at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. She published the first scholarly monograph of Shirley Hazzard’s writing and recently edited two volumes of Shirley Hazzard’s work: We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think: Selected Essays and Collected Stories. This is her first biography.