How Leonora Carrington Used Tarot to Reach Self-Enlightenment

Gabriel Weisz Carrington on His Mother's Quest for Mythic Revelations

Leonora was a restless voyager through deep journeys, always in quest of mythic revelations. Her aim was to repair a shattered world and a means to live in it, unearthing the many images that came her way. Guided by her intuitive meanderings she came upon the I Ching or Book of Changes, carving beautiful wooden tokens and dwelling on the secret language of hexagrams to reach her own patterns of change. She also took other paths like divination, magic and meditation, since all developed into components for a complex mental vehicle that became articulated into her own navigational devices, launching her towards a wilderness of mind. However, she chose the tarot and all the exotic legends surrounding the Bohemians or gypsies; close companions to her imaginal self.

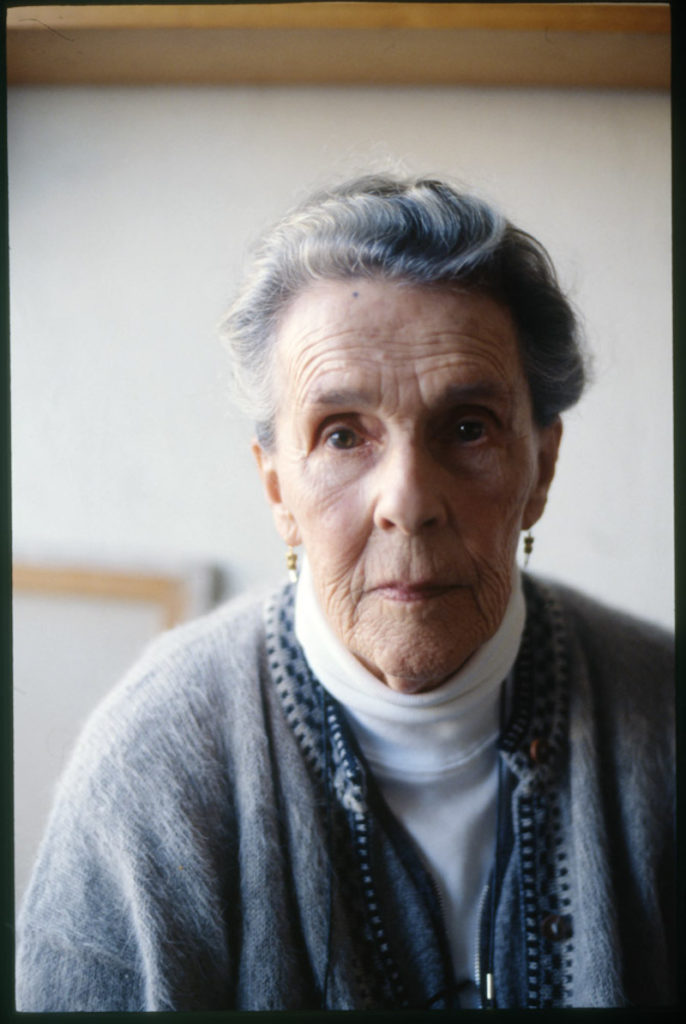

Leonora Carrington at home in Mexico D.F. 1998

Leonora Carrington at home in Mexico D.F. 1998

During one of those conversations we use to have, she mentioned how the gypsies intervened to help her flee from her captors once she left the mental hospital in Santander bound to Portugal; then adding in a proud demeanor, “Gaby, we come from the tinkers, an lucht siúil or the walking people.” Leonora fantasized living and traveling in a gypsy caravan pulled by Vanner horses through the roads of the Irish countryside.

My mother had a permanent inquiring mind, “The tarot is the most important device in cartomancy.” From one of the bookshelves in her room she pulls out Le tarot des imagiers du Moyen Age by the Swiss occultist Oswald Wirth. Leonora dreamily enumerates the cards or tarots, “The Magician, the High Priestess, the Empress, the Hierophant, the Lovers… ”

“You know, I might design my own deck.”

“That is a splendid idea.”

Pointing to another book, she goes on, “The Chariot, and look what Edward Waite has to say. This princely figure (…) led captivity captive, he is conquest on all plains—in the mind, in science (…), in certain trials of initiation. The chariot is drawn by two sphinxes.” I can feel her enthusiasm, surely this state will lead her next project.

The following morning, we walk to a nearby artist’s supply shop and purchase a couple of thick paperboard sheets. A few days go by, I enter her studio, on the table I find an open tarot book. It’s The Tarot of the Bohemians by Papus. I can see the VIIIth card, Justice. Not only a symbol of justice but also “an equilibrium, between the destruction of the works of man accomplished by Nature.”

As Leonora enters the studio, I ask about this card; she always considered that people had no respect for Nature. “I agree, but don’t you think it also refers to a denial of inner nature?”

“Well, you cannot separate one from the other, your mind blends with nature.” During the next months she prepares the 22 cards, carefully cutting to size each one of them, after which each card was given a coat of “Blanco de España.” While working, Leonora explains, “This white paint will even out any porosity of the paper, I want a smooth surface, so we will just let these dry out, then I will be ready to paint each one.”

A lot of research went into the tarot, I saw her pouring over Oswald Wirth’s tarot; The Pictorial Key to the Tarot by Arthur Edward Waite; The Tarot of the Bohemians by Papus among many others. However, Leonora’s rendition mirrored her own creative individuality. A case in hand is the Hanged Man, the XIIth card, differing from Waite’s in that hers, instead of the nimbus about the head, the figure dons a golden helmet. This card of the Arcana, as Papus reveals, represents “anything that stretches, that raises, that unfolds like an arm, and has become the sign of expansive movement.”

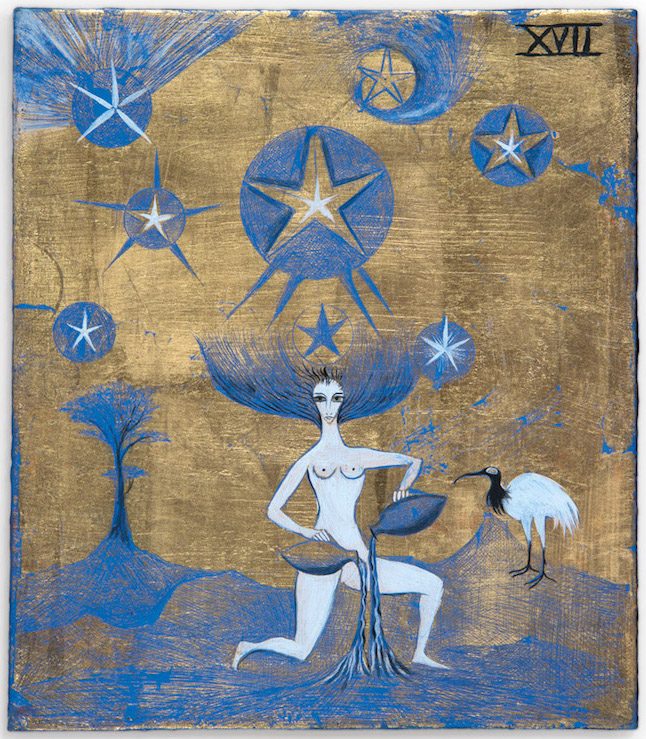

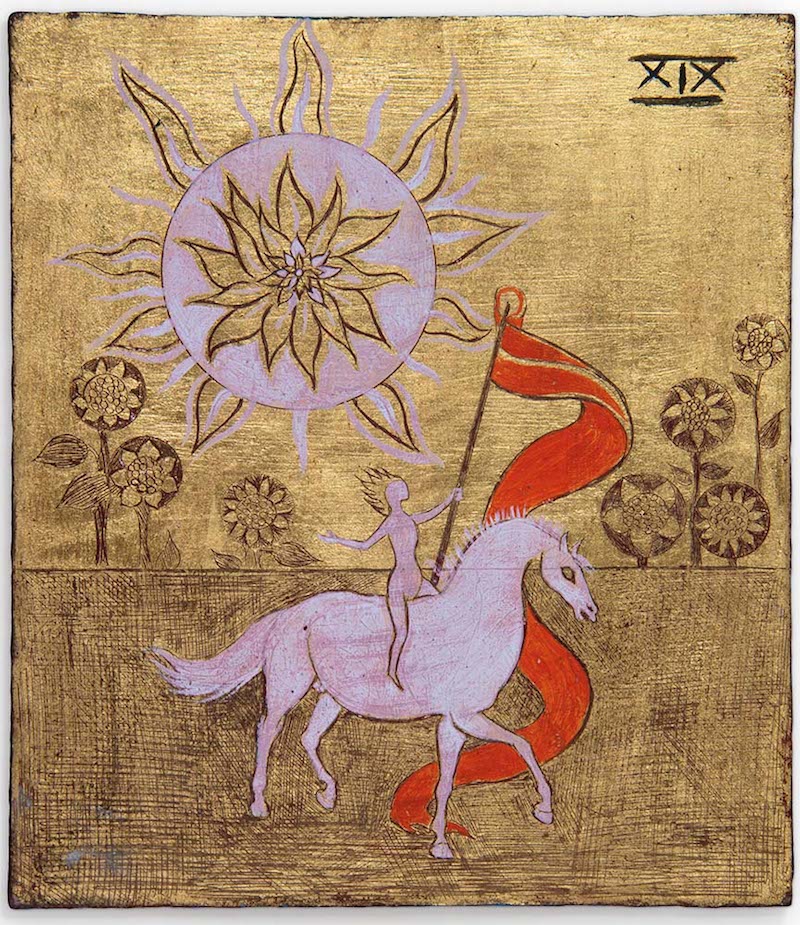

The IVth the Emperor, the Xth Wheel of Fortune, the XIIth the Hanged Man, the XIVth Temperance, the XVIIth the Star, the XVIIIth the Moon and the XXIst the World, underwent a well-known medieval gold and silver gilding procedure. A thin gold or silver metal leaf was delicately cut and then set over each of these cards. With a fine brush she dropped the gold or silver leaf over a surface previously prepared with fresh glue.

“Come nearer, the gold leaf s slightly wrinkled.”

“What are you going to do about it?”

“Well, see this?” Leonora pulls out from some drawers a tool. “This is known as a ‘wolves’ tooth.’ I use it to burnish the gold or the silver leaf, the hooked tip is made out of agate.”

Her timing was crucial for a perfect result. Now we can admire the mastery of each of these cards and the rest of the deck. While preparations are made for the Major Arcana or the set of 22 cards, Leonora mentions that the earliest known reference to these cards was when Alfonse XI banned them in 1332. I later found this information in Bill Butler’s Dictionary of the Tarot.

“Why don’t you throw it for me.” After a moment’s silence she brings the 22 cards. I drew 22 cards randomly and placed them on the dining room table in front of her. Then the cards were spread in a semi-circle.

“I will arrange them in seven piles, from right to left, you have to choose any number under 23.” After which she picked the fifth card. The tarots are now placed to make a cross. This one will go on my left, it represents what can be affirmed or what is favorable. This other is what is denied, hostile and unfavorable. She places a card in the middle, this is what shall be discussed, what will turn convenient for you. And finally, we come upon a solution or a result by comparing the affirmation to the negation.

Her aim was to repair a shattered world and a means to live in it, unearthing the many images that came her way.

Leonora seemed to play with a deep-rooted collage, where the Tarot of Marseille was recreated into a new narrative and illusionistic game of personal search. Upon this path a unique myth was born, along with the discovery of her own innermost tarot.

This was how she trod between her conscious inquiry that encompassed multiple tarot books, and the releasing of her unconscious creative persona. She contacted what Breton might once have called “convulsive beauty”—a means to dwell in the veiled life of each character associated to that explosivity of creative forces. For Leonora, all this meant a quest toward a personal Surrealist object with a similar profile to a subliminal object, one loosely associated to the symbolic manifestations behind the tarot. Leonora’s approach turned each card into an inmost subversive narrative, concocting the traditional sagas from the Major Arcana with her subliminal characters. This might place us in the midst of exploring perception to reach that place of psychological differences, turned into the unknown underworld where images are found. It seems we better follow Leonora’s voice.

I don’t paint dreams, as far as I know.

Dreams are in a different space.

There must be

Many, many different spaces.

Everything is interrelated.

Everything in the phenomenal world

Would be entirely related.

They are vehicles

moving from one liminal place

to another—

one subliminal place

to another.

The tarot is not meant solely for divination purposes. Each suggest navigation devices where a poetics of the unconscious is available for immediate exploration. These cards may be consulted as subliminal objects, separate from rationality; they give access to magical environments. Because the subliminal body might be conceived as an out-of-the-body experience, it also entails a liberation from the rational corporeal form. This body is able to travel through unconscious domains. Ultimately it is endowed with a projective capacity that enables an exploration of the visionary world.

As I open The Dictionary of the Tarot, what Butler states about the Fool is that it is appended to the trickster, “one of the most important symbols of the unconscious mind.” Interestingly, he associates this tarot to the “self at the beginning of the journey.” A trickster, one might surmise, is an experiment with a magical self—also found as the court jester, or court dwarf. Leonora follows the conventional numbering, so it appears as the zero card. The trickster is bitten by a ferocious cat or lynx. This character is unaware of the cat biting his leg, he is the incarnation of the unconscious and is oblivious to where he is heading. Obviously, he relates, as many other characters do, to the hidden aspects of the self in each of us.

An interesting conversation with Leonora took place regarding another book she was consulting. Joan P. Couliano, who wrote about desire as “The pursuit of a phantasm and the phantasm itself belongs to a world, the imaginary world—the mundus imaginalis whose loftiness Henri Corbin described as ‘dealing with its penumbra.'”

No sooner had she quoted this to me she exclaimed, “The Fool is the shadow of knowledge, he is the enigmatic other!”

I responded, “The Ghost in the psyche.”

“Indeed… ” she answered slowly drifting away from the conversation to retire into a private domain. I suppose Leonora was drawn to this card because she was fascinated by the trickster. Since I had the Paul Radin book in my bedroom, I came back with it. “Do you want me to read what I found?”

Wakdjunkaga, or the Winnebago trickster in Siouan language, stems from tricky. “The myth of the trickster is found among North American Indians [sic]. They inhabited an area which extended from South Carolina and the lower Mississippi River northward and westward (…) to Wisconsin, North and South Dakota [and it even reached Canada].”

She took special interest in an essay by Jung on the trickster, where we are told about his “sly jokes and malicious pranks, his powers as a shape-shifter, his dual nature, half animal, half divine… ”

“Like most of characters in my paintings,” remarked Leonora; then she recalls something said by Wirth. “The Fool belongs to a domain of the intelligible.”

We also find the trickster as an archetype, Jung calls attention to these traits, “He is so unconscious of himself that his body is not a unity… ”

One would contest that the unity of a rational body does not correspond to a subliminal one. Jung discusses the trickster as an archetype and frames this character as a manifestation of an early development of consciousness. Leonora and I exchange views on how Jung hints at a kind of trickster mood in masquerades, probably modeled from the Cervula or Cervulus.

Since all this was so motivating for Leonora, I managed to find that the trickster originated from the Roman Saturnalia and kalends feasts, including other festivities to celebrate the Christmas period. Many events enacted the Old and the New. “Skin clad mummers led by Cervulus or hobbyhorse and other symbolic figures.” The trickster undergoes multiple shape modifications, according to Jung the archetype brings forth a “transformation of the meaningless to the meaningful.” So even though the zero card of the Fool depicts him as incapable of discernment, he can manifest the meaningfulness of a quest directed to self-knowledge. With this view the tarot is a navigational device, enabling us to visit a mostly muted domain in which perceptions and sensations are silenced.

The strategies of a coercive force against a free psyche set upon enslaving our inner trickster, to inhibit and render it powerless. Wirth warns us about the fool who “carries a treasury of stupidities and insanities,” and adds that “we have to be reasonable so as not to leave the limited domain of reason.” Jung joins in this deprecatory mode when he remarks that the trickster “preserves the shadow in its pristine mythological form, and thus points back to a much earlier stage of consciousness which existed before the birth of the myth when the Indian was still groping about in a similar mental darkness.” I often challenged these views while exchanging ideas with Leonora. Who gave him the right to personify the alleged archeologist of “primitive mentalities”? Be that as it may, both Wirth, under his mask of reasonability Jung, with his racist babblings, are blinded by reductionist and rationalistic views.

One would contest that the unity of a rational body does not correspond to a subliminal one.

Leonora’s approach to the tarot was an imaginal affair. The game reached a realm of inner images that took a life of their own. It brought a liberation of subjectivity, often entrapped by our own lifelong training in a repressive objectification. The game opened a subjective territory or playing ground where the keys to the individual’s psychic forces are made to work. Since each card engages emotions that connect to the images, these may become emotional personifications. Leonora’s VIIth card, or the Chariot, is interpreted as talent, understanding of oneself, Grand Architect. However, it might also be read as disorder, a possible accident, bad news. This version seems to narrate the two sphinxes drawing the chariot. The charioteer answered the riddle of the sphinx, so in Waite’s interpretation, the card represents “a triumph in the mind.” A different elucidation is that the victorious one “leads a gentle white beast and a savage dark one… ”

However, for Leonora the male charioteer is to be guarded by two watchful and enigmatic female figures; such an addition doesn’t appear in any of the tarot books that I consulted. Leonora wants to disclose the mystery of the inner animal. Could we envision a game of emotions and fantastic beasts who know the answer to the permanent question, “Who am I?” while the white “emotional” sphinx and the savage dark sphinx haul us into a complex state of being?

We know that in the tarot game the person always asks something, and a reply is furnished through the symbolic workings of the cards, but in the end, we are the ones that provide an answer. Returning to the sphinxes, a hybrid constellation combining half a woman and half a lion, who addressed enigmatic questions to the passerby, such that could only be dealt by the power of mind; additionally, this creature stands for enigmas and the ineluctable. The sphinx as a riddle-maker is an interesting player in this story. Leonora was seduced by the symbolism attached to this entity, which Jung identified with “the feminine instinct,” but we could add also, informed with a deep-rooted intelligence. At this point let us not forget those two enigmatic female figures “balancing and flanking the male force.” In Leonora’s tarot we encounter an imaginal player who has traditionally been excluded from any participation in the domain of mind. A place guarded by those who discourage any form of play, except when justified by a limited and impoverished domain complicit with a restrained and rationalized set of rules, where power games thrive.

Earlier I mentioned a poetics of the unconscious, connected to a Surrealist creative underground which at some point relates to Leonora’s tarot. All of a sudden, I’m struck by the idea that the trickster returns—a revenant—as a figure of automatism. An instigator of an unconscious revolt, an automatism envisioned as “a language (within the hypnotic dream) or that which dissipates the control of reason (…) there is a questioning of the subject by itself and the meaning of all language, of all human communication.” The question arises to suggest a dwelling associated with such poetics, in what Breton portrays as the hazard objectif; also aligned to a definition of this figure.

In addition to Leonora’s objective chance—availability to the exploration of an imaginary region in her tarot—Breton plunged into a hazard objectif or objective chance in a specific frame of mind. “Today once more,” he declares, “I expect nothing else but my availability, a thirst to wander, to encounter everything, assured that it will keep a mysterious communication with other available beings, as if we were summoned to a sudden reunion.”

Leonora’s approach to the tarot was an imaginal affair.

Objective chance, he admits “is the confluence of phenomena which manifests the invasion of the marvelous in everyday life.” A state of mind not exclusively accepting this availability but also a disposition to allow the invasion of the marvelous, is conducive to this poetics of the unconscious omnipresent in Leonora’s tarot. The player’s imaginal nature assimilates “the magical power of the hazard objectif, retaining the force of a conjuration, that creature [of sublimity] and truth,” as was so beautifully put by Carrouges.

Leonora’s tarot is endowed with a subliminal iconography, a window opening to a performance of the marvelous. What retains such a seductive allure is that whenever we get the opportunity to play with these cards, each one of us is invited to daydream; the cards also guiding players and observers through an adventure into an unknown domain of feeling and subliminal transformation.

A cautionary note might well be heeded, “In the Surrealist universe, an automatic set of symbols or voluntary ones abound, plastic expression by itself or the object for the object’s self is no longer valid… ” Nacenta’s words suggest an insight into subliminal transformations associated to “automatic symbols” as I understand them; emerging from an internal voice which becomes materialized in objects or written materials—this provided me with a thematic background to read Leonora’s tarot beyond the conventional meanings attached to the original game, along with the figure of a poetics of the unconscious associated to both automatism and objective chance.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Tarot of Leonora Carrington. Used with the permission of the publisher, Fulgur Press. Text copyright © 2021 Susan Aberth, Tere Arcq, and Gabriel Weisz Carrington. Photo copyright © Estate of Leonora Carrington/ARS, New York.

Gabriel Weisz Carrington

Gabriel Weisz Carrington is a poet, playwright, theatre researcher and comparative literature researcher. He collaborated with Leonora Carrington in a few creative endeavours; a joint project with the Dark Book, building sets for theatre, cinema and assisting Leonora with a few sculptures. He holds a doctorate in Comparative Literature and is a professor of Comparative Literature at Universidad Autónoma de México. He is the first-born son of Leonora.