How LA Became a Destination on the Rare Book Trail

In the 1930s, Bookstores Were a Haven Artists, Actors, and Raconteurs

The book business is almost a business, similar to a bar . . . one is drunk on books and the other is drunk on whiskey; and in each place they hang around.

–Louis Epstein

![]()

Nobody ever thinks of Los Angeles as a rare-book town anymore. But for most of the 20th century, it was one of the best in the world. Supported by private collectors and institutional buyers, a large group of booksellers sold all manner of rare books, and the city became a destination for those on the rare-book trail. Not only is book culture elemental to the literary and art history of Los Angeles during the 20th century, it is also part of Los Angeles’s paradoxical past and shadow history, existing quietly amid the flimflammery of boosters, the ballyhoo of Hollywood, and the outré architecture.

As unexpected as a Los Angeles rare-book legacy may be, even more unpredictable is the fact that it was two Texans who loom large in the city’s book lore: Jake Zeitlin and Stanley Rose. Arriving separately from the Lone Star State in the early 1920s, each was devoted to books, and while their styles differed, their charismatic personalities attracted writers, artists, and assorted Hollywood types as both friends and customers. Enjoying the company of creative minds, Zeitlin and Rose became legendary figures at the centers of two distinct groups: one artistic and bohemian, the other, fueled by alcohol and male camaraderie. As serious as they were about books, Zeitlin and Rose also loved hanging out, carousing and partying—and, of course, they knew each other.

Jake Zeitlin (1902-1987) hitchhiked to Los Angeles from Fort Worth in 1925, intending to be a guitar-playing poet. Instead, he became LA’s leading rare-book dealer. Over a 60-year career, he sold books, published small-press editions, and mounted important art exhibits; he gave photographer Edward Weston his first show and was instrumental in jumpstarting the careers of many local artists. He was active in many liberal causes throughout his long life, including as a campaign activist in Helen Gahagan Douglas’s 1950 senate race against Richard Nixon. Aspects of this rich, creative life have been chronicled by various historians over the years.

Stanley Rose (1899-1954), born in the cattle town of Matador, Texas, arrived in Southern California after serving in World War I and became Hollywood’s most notorious bookseller of the 1920s and 1930s. He began his career by peddling books out of a suitcase he lugged to the movie studios—books that provided the studios with possible plots. And for those in search of other thrills, he offered pornography and bootleg liquor—his suitcase had a false bottom, and it was the era of Prohibition. He is remembered by book people and film historians as the model for the shady bookshop in his friend Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, and is mentioned in passing in seminal novels and accounts of the period. Like Zeitlin, Rose was well known by his contemporaries, but unlike him, he has been mostly overlooked in histories, in part because he died fairly young and left few traces, and in part because his reputation was tainted by his alcoholism.

Old Books, New Shops

Although Zeitlin and Rose changed the style of LA bookselling, they did not reinvent it—bookshops had been a part of the city’s culture since the 1860s. By the 1880s, when throngs of prosperous, well-educated settlers began arriving in the city during the real estate boom, bookshops began to flourish. The city supported a community of booksellers that developed downtown along and around Sixth Street. Easily accessible by the Pacific Electric interurban railway system whose cars pulled in at the central station at Sixth and Main, shops like those of Ernest Dawson and C.C. Parker provided not only popular literature, including LA’s first bestseller by a local author, Horace Bell’s Reminiscences of a Ranger (1881), but also such rare titles as 16th-century books illustrated with woodcuts and first editions of Dickens. Bookselling in Victorian Los Angeles remained sober and steady until the Roaring Twenties, when the rise of the film business created a new location—and a new ambiance—for the selling of old and rare books: Hollywood.

“The stores were like clubhouses for the owners’ patrons and friends, hangouts for writers and artists. They were places where ideas were discussed and argued, the conversations often enlivened by illegal hooch, especially during Prohibition.”

The bookshops of the 1920s possessed an alluring mystique mixed with an avant-garde sensibility that was connected to the sexy world of artists, actors, writers, directors, drunks, and raconteurs who were part of Hollywood’s subcultures. Just as the movie stars rose to fame, some local booksellers also became celebrated for their colorful lives. Gone were the staid shops of their forefathers; the new generation of booksellers, those born around 1900, created a new way to sell books that mirrored the new era.

Often, the bookshops also contained art galleries, reflecting the owners’ cultural cachet, aesthetic interests, and friendships. The stores were like clubhouses for the owners’ patrons and friends, hangouts for writers and artists. They were places where ideas were discussed and argued, the conversations often enlivened by illegal hooch, especially during Prohibition. Furthermore, studios looking for new stories on which to base movies bought up loads of novels; they also scooped up art books along with costume and architecture books as source material for films with historic settings.

Stanley Rose opened his first bookstore, the Satyr, in 1925 on Hudson Avenue near Hollywood Boulevard. (Was it a coincidence that the man who became known for his backroom bar selected a satyr as his emblem? But then, it was also the symbol of his astrological sign, Sagittarius.) A year later, when Rose added two partners, the Satyr moved into swank new quarters in a deluxe Spanish-style building at 1622 North Vine, next to the Brown Derby, in the hope of finding customers among the restaurant’s Hollywood clientele. It worked.

Jake Zeitlin, who opened his first bookshop in 1928 on Hope Street near Sixth downtown, recalled that the Satyr “really got the cream of Hollywood’s book business; they had a spectacular bookshop. Everybody that was coming along in Hollywood was there.” Zeitlin’s shop, just 12 by 8 feet, was no more than a hole in the wall. His friend, the printer and book designer Ward Ritchie, called it “the smallest bookshop in existence.” It was found “in the back stairway of a derelict building that may once have been a brothel.” This louche location was perfect for Zeitlin, the would-be poet—but he had to pay the bills and found his way to selling books rather than writing them. Lawrence Clark Powell called Zeitlin’s shop “a crack in the wall” that was unlike any other bookshop, “a place fragrant with oil of cedar. It was the bookshop of Mr. Z.”

The Satyr wasn’t alone in Hollywood—the area had many other bookstores, especially on Hollywood Boulevard, including the Hollywood Book Shop, Louis Epstein’s Pickwick Book Shop, Unity Pegues, Esme Ward, and Leonard’s. Nearby were at least two shops that specialized in metaphysical and occult books: Verne’s on Cahuenga and Ralph Kraum on Sunset. (Kraum was also Ronald Reagan’s astrologer—long before Reagan met Nancy.) The Hollywood Book Shop, at Hollywood and Highland, was known for its erudite owner, Odo B. Stade, who led an improbable life of scholarship mixed with adventure—a learned bookseller, he had also been a diplomat, gun-runner, naturalist, silent movie actor, stunt flyer, writer, translator, and forest ranger. Stade was very successful, especially with Hollywood collectors, but during the Depression, he sold the shop and began writing, including collaborating on Viva Villa, a book based on his experiences in Mexico with Pancho Villa that was sold to MGM, became a successful movie, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture in 1935.

Book collecting became a favorite pastime of many in the increasingly profitable film business. Actors, directors, and producers had loads of cash and they built superb collections: Jean Hersholt acquired an extensive collection of Hans Christian Andersen (now at the Library of Congress). Joseph Schildkraut’s library contained 17,000 volumes. Ronald Colman was buying up first editions of Shelley, Keats, and Oscar Wilde. Rod La Rocque went in for Dickens, Thackeray, and fine bindings. John Barrymore collected first editions, art books, and books on the sea. Charlie Chaplin bought Greek tragedies and classical literature, while Rudolph Valentino acquired books on costume, arms and armor, and yachting. Some actors were reputed to collect erotica, when they could find it. And it was at the Satyr where their chances were good.

Downtown, Zeitlin’s artistic nature and magnetic personality attracted not only customers, but also artists and writers, and after a year, he was able to move to somewhat larger quarters on nearby Sixth Street, on LA’s old-book row. Among Zeitlin’s friends was architect Lloyd Wright, who designed the new shop and created Zeitlin’s distinctive grasshopper logo. Zeitlin chose the grasshopper “because like the grasshopper in Aesop’s fable, I fiddled and sang in the summertime and froze and starved in the winter.”

Vice on Vine

In 1930, Stanley Rose had a scandal on his hands when he was convicted for violating copyright laws by publishing a pirated edition of a scatological humor book. Although he published it along with his partners, it was Rose who took the rap since he was the only unmarried partner and without a family to support. Although it wasn’t for pornography, it served as a warning to would-be smut peddlers, including Rose, that the law would deal harshly with them. His generosity got him a 60-day jail term. Still, Rose had connections, and not just in Hollywood.

He immediately contacted a good friend, Carey McWilliams, a young lawyer and writer who became prominent in left-wing causes (chairing the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee, for example), and who would write one of the most insightful books ever published on Southern California, Southern California: An Island on the Land (1946). McWilliams was able to get Rose released, and he arranged for the partners to buy out Rose’s interest.

“Chandler is said to have based Geiger’s shop [in The Big Sleep] on his friend Stanley’s place, especially since Rose was convicted in the piracy case and was known to sell ‘dirty books.'”

Rose opened his own bookstore directly across the street from the Satyr—the Stanley Rose Bookshop. As McWilliams recalled: “After a few drinks, Stanley would now and then emerge from the store and, to the amusement of his customers, swagger to the curb, shake his fist at his two former associates across the street, and hurl eloquent Texas curses at them.”

Rose was an inveterate roué who loved drinking, hardboiled writers, and hosting his friends; he became the center of an unusually creative group: writers who were known as much for their novels and Hollywood scripts as for their drinking. Rose provided the drinks—he preferred whiskey sours, without sugar—in his back-room bar to such writers as James M. Cain, John O’Hara, William Saroyan, John Steinbeck, Hans Otto Storm, Nathanael West, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, the subjects of Edmund Wilson’s 1941 critical study of California novelists, The Boys in the Back Room. Although Wilson does not reveal the location of the “back room,” it was common knowledge in Hollywood that it was Rose’s. Zeitlin described Rose as “a man who had good friends among the bootleggers. During Prohibition you could always get a drink at Stanley Rose’s . . . if you wanted a drink at any hour of the night, you could always knock on Stanley Rose’s back door, and he was there at the back of the shop with a jug.”

Rose’s was the preferred hangout of many other accomplished writers and actors: William Faulkner, John Barrymore, W.C. Fields, Edward G. Robinson, John Fante, Budd Schulberg, Gene Fowler, Horace McCoy, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and even Marion Davies, who found Rose charming enough to invite him to San Simeon for a weekend. Hedda Hopper called him “Stanley Rogue.” Budd Schulberg includes Rose’s shop in What Makes Sammy Run. Nathanael West mentioned him in The Day of the Locust.

But it is in Raymond Chandler’s work that Stanley Rose, or at least his bookshop, achieved the greatest fame. In one of the most celebrated scenes in movie The Big Sleep (1946), based on Chandler’s novel of 1939, Philip Marlowe, posing as a geeky book collector, enters A.G. Geiger’s bookshop and asks the snooty clerk a set of obscure questions about two old books. She fails to answer them properly, revealing that she knows nothing about rare books, thereby setting up the scenario in which she, and the entire bookshop, are exposed as frauds: It is a front for the backroom sale of pornography. (Erotica and pornography are the shadow side of “rare” books.)

As Chandler described it: “A.G. Geiger’s place was a store frontage on the north side of the boulevard [Hollywood Boulevard] near Las Palmas . . . The entrance door was plate glass, but I couldn’t see much through that either, because the store was very dim.” Chandler is said to have based Geiger’s shop on his friend Stanley’s place, especially since Rose was convicted in the piracy case and was known to sell “dirty books”—and Rose’s shop was on Hollywood Boulevard’s north side, between Las Palmas and Cherokee.

But Marlowe isn’t done. Not finding Geiger at the shop, he goes down the street to the Acme Book Shop, hoping for information on the elusive Geiger. There, he encounters another woman, this time, a comely, intelligent one. Their conversation, with its witty wordplay filled with sexual innuendoes, sets another tone for rare bookshops, showing them as places of intrigue where men and women could engage in sexy, bookish banter—with possible romantic results. Hollywood noir and rare bookshops have been intertwined ever since, thanks, in part, to Stanley Rose.

Art & Publishing

“Stanley was the least bookish person I’ve ever seen and I often wondered whether he ever read a book,” recalled artist Fletcher Martin of Rose’s Prohibition-era activities. “He ran a shop which was a combination cultural center, speakeasy, and bookie joint. Stanley would get whiskey and/or girls for visiting authors . . . The ambience was wonderful, something like your friendly local pool hall. He liked artists and always had a gallery in the back.”

One of the first art galleries in Los Angeles to show modern art was the Rudolf Schindler-designed Braxton Gallery, located at 1624 North Vine, just across the street from Rose. It was opened in 1929 by Harry Braxton, a former publicity agent from New York, who, with his wife, screenwriter Viola Brothers Shore, was part of a glamorous Hollywood in-crowd that included Josef von Sternberg, Jack Warner, Darryl Zanuck, Harold Lloyd, Joan Crawford, and many others. Braxton exhibited modern art at a time when it was often disparaged in Los Angeles, but he managed to meet several discerning collectors, including Walter Arensberg and Josef von Sternberg, and he succeeded, for a while. His major achievement was arranging with the pioneering art entrepreneur Galka Scheyer to exhibit the work of the Blue Four: Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger, and Jawlensky.

“Zeitlin’s bookshop became a meeting place for literary and artistic people and developed not only as place to buy books and prints, but also as clubhouse of Modernism.”

Perhaps inspired by Braxton’s brief gallery success, and undoubtedly sharing many of the same customers, Rose opened a gallery of his own in October 1934, calling it the Centaur Gallery—the former satyr was now a centaur, and Rose used an image of the half-man/half-horse archer as his logo. Located on Selma near Vine, the Centaur Gallery took over where Braxton left off, exhibiting the work of local and international modern artists. Rose, whose background in art was negligible, had the smarts to hire knowledgeable directors, and the gallery held impressive, well-reviewed exhibitions of work by major artists including Archipenko, Cézanne, Dali, Ernst, Gris, Léger, Miró, Picasso, Renoir, and Rouault; he also exhibited photographs by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, and gave Philip Guston his first show.

Zeitlin’s bookshop became a meeting place for literary and artistic people and developed not only as place to buy books and prints, but also as clubhouse of Modernism. While Stanley Rose attracted writers and serious drinkers, Jake Zeitlin attracted writers and bohemians, more prone to drink wine than whiskey. And while Rose played fast and loose with liquor and copyright laws, Zeitlin took another path. About the time that Rose was in court during his piracy case, Zeitlin had set up a small—and legitimate—publishing concern in 1929, Primavera Press. Taking its name from the original Spanish for Spring Street, Callé de Primavera, the press specialized in reprinting classic works of California literature and history; it was done in by the Depression in 1936, but during its seven years, Primavera Press published 26 books.

Zeitlin’s success led him to move again, and in 1934 he opened a larger shop on Sixth Street, again, designed by Wright. In 1938 he moved again, this time farther west, to a carriage house at Carondelet and Wilshire. Among the artists he exhibited were Edward Weston, Peter Krasnow, Henrietta Shore, Paul Landacre, Rockwell Kent, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. Zeitlin’s craggy good looks made him an ideal subject, and many of his artist friends, including Weston, Landacre, Will Connell, and Max Yavno, made portraits of him.

The Musso & Frank Years

In January 1935, Rose moved the bookshop and gallery to a single location at 6661½ Hollywood Boulevard, conveniently located next to Hollywood’s prime watering hole and restaurant, Musso & Frank. This was ideal for Rose, who used Musso’s bar as an extension of his office while continuing to maintain his own back-room bar at the shop. (It didn’t hurt that the offices of the Screen Writers Guild were across the street at Hollywood and Cherokee.) As McWilliams recalled: “Stanley was a superb storyteller and a very funny man whose generosity was proverbial. In the late afternoons, as he began to warm up for the evening with a few drinks, he would hold court in the store, entertaining whoever happened to drop in, and the performance would invariably continue into the early morning hours in the back room at Musso’s.”

After Rose’s gallery director left in 1937, the exhibitions became more modest, with shows of amateur or little-known artists, reflecting Rose’s lack of knowledge about art. In 1938, no doubt arranged as an act of kindness by his many friends to keep the gallery afloat, Rose held an exhibition of movie star memorabilia that included such tidbits as a caricature of Charlie Chaplin by child star Jane Withers. One of the gallery’s last exhibitions, in June 1939, was of whittled wood figurines by Carl Frim, a Swedish masseur to the stars.

Rose tried to carry on, but as a businessman, he wasn’t too careful and his lax habits caught up with him. He lent money to anyone who asked and allowed his pals to charge their book purchases—and many never paid their bills. As Bob Thomas, a reporter with a Hollywood beat, recalled, “The trouble was that Stanley had too many friends. So many of them borrowed books and money that he went out of business.” Losing steam, the gallery and bookshop closed at the end of June 1939. Rose had gotten married that April, and moved with his wife to San Bernardino, where her parents lived. There, he tried the simple life by raising tomatoes. It wasn’t for him.

By 1941, Rose was back in Hollywood, where he became an agent—with one client, at first, William Saroyan, who offered to sign with him partly because Rose needed the money, but also, as reciprocation for countless meals and drinks, and for the many Saroyan books Rose had sold in his shop. Saroyan had been negotiating at the time with MGM for a contract to write The Human Comedy, and received $60,000 plus $1,000 per week. Saroyan gave Rose $10,000 as his cut, more than the usual ten percent, a real act of charity. Rose’s drinking was legendary by this time, and the studio used it to advantage: Whenever a meeting was scheduled at MGM, one of Louis B. Mayer’s assistants made sure to give Rose all the whiskey he wanted, rendering him unable to negotiate a contract. According to caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, Mayer once asked Saroyan, “Who the hell is this loafer you bring in with you all the time?” Saroyan replied: “That’s my agent.”

Rose struggled on, representing a few more clients, including actor and author Audie Murphy and Pat McCormick, a Texas beauty pageant winner who became the first woman bullfighter. (After all, Rose was from Matador, Texas.) Another old friend and fellow Hollywood bookseller, Louis Epstein, let Rose use his Pickwick Books as his mailing address when Rose was living nearby in a seedy hotel. As Rose’s drinking became more debilitating, his wife left him, taking their young son with her. Rose died in 1954, broke and alone, a dismal ending for the man who was once the droll center of a dazzling crowd.

By 1948, Jake Zeitlin had enough money to buy his own building, the Red Barn at 815 North La Cienega, in what is now West Hollywood, where he continued to sell books until his death in 1987.

Zeitlin was at the center of so many social and artistic circles in LA, and he had a hand in organizing and encouraging so many creative endeavors that it’s easy to lose track of them all. He helped Frieda Lawrence sell D.H. Lawrence’s manuscripts; got screenwriting jobs for Aldous Huxley while publishing two of his books; and he sold to and advised Dr. Elmer Belt as he acquired his massive collection of the works by Leonardo da Vinci, now at UCLA. Zeitlin’s personal charm, combined with his knowledge of books and art, made him someone book people sought out for 60 years.

How unpredictable, how unexpected, and yet, how like Los Angeles to have had two Texans at the center of its rare-book history. But then, LA, magnetic and receptive, has always attracted eccentrics, dreamers, and mold-breakers. Its reputation—and shadow history—depend on them.

__________________________________

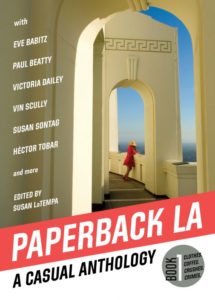

From Paperback LA. Used with permission of Prospect ParkBooks. Copyright © 2018 Victoria Dailey.

Victoria Dailey

Victoria Dailey is a writer, curator, antiquarian bookseller, and lecturer. The co-author of L.A.’s Early Moderns: Art, Architecture, Photography and a contributor to Songs in the Key of Los Angeles: Sheet Music from the Collection of the Los Angeles Public Library, as well as Paperback L.A.. Dailey contributes humor and essays to The New Yorker and L.A. Review of Books.