How Josephine Baker Learned to Hate the Nazis Before Most of America

Damien Lewis on an American Icon's Transformation from Dancer to Spy

As Josephine Baker had declared in her 1927 memoir, penned with French writer Marcel Sauvage, she abhorred the stereotyping of women and she cherished her freedoms. But since then, a far greater challenge—a far greater menace—had raised its ugly head. In 1926, she had left Paris to tour Europe, her itinerary taking her finally to Berlin.

Not yet a decade after the horrors of the First World War, there was a wild exuberance to Germany’s capital city, and the bright, brash nightlife felt more like the America she had known in her youth—Harlem, or the Chestnut Alley district of her native St Louis—than it did the refined airs of a historic capital of Europe.

This was Germany prior to the rise of Nazism, and there was a hectic decadence about the city, a need to hunt for sensation and thrills, as an antidote to the horrors of the Great War. Not only had Germany suffered during that conflict, but this was the nation of the vanquished and there was a need to party and forget.

Raised in dire poverty in the city of St Louis, Josephine often had no uniform or even shoes to wear to school. Teased, rejected, mocked, she’d played the fool and had mostly hated school. She was far happier leading her street gang stealing coal from locomotives, to sell to rich white folks. She’d proved the fearless and the wild one, climbing onto the rail cars to throw down handfuls of the dirty black rock, so the rest could stuff their sacks full.

She was not only a symbol of the decadence they abhorred, she also epitomized the “racial impurity” they despised.

Often, the train would jolt into motion even as she was so engaged. Invariably, she would remain on her precarious perch, hurling down more coal, as the locomotive began to gather speed and her street pals yelled for her to jump. Typically, she’d push it to the very limit, throwing herself free just before the train had reached a speed at which the impact could have proven injurious or even fatal. Often she went barefoot, and during the coldest months she would resort to dancing along the streets in an effort to ward off the chill.

Unsurprisingly, she thrilled to the wild excess of Berlin in 1926. Fearful that her stardom and good fortune might prove transitory—that she might sink back into the abject penury and hard grind of her youth—she chased fame and fortune relentlessly, lest it slip away. She also, unashamedly, rewrote and recast her origins, her parentage especially. “I don’t lie. I improve on life,” she once told a reporter, who had commented pointedly on the contradictory versions of her family history that she had told.

During her first Berlin tour, Josephine’s performance in La Revue Nègre—the show that had brought her from New York to Paris, in 1925—proved a sell-out hit. In Germany, the concept of the ‘noble savage’—supposedly a more primitive and natural form of human existence, one that predated modern, mechanized existence—was all the rage. Josephine’s headline act in La Revue Nègre was seen to embody all of that, her near-naked dances—she believed she was born to move, rhythm hard-wired into her soul—captivating audiences, just as the nacktkultur (nudist) movement was taking Germany by storm.

But at the same time there was an extreme right-wing ideology starting to take hold, which aimed to purge the country of such “immorality,” and to build a nation that was “healthy, fit and strong.” This was the nascent Nazi movement, and its storm-troopers at the time were the so-called Brownshirts. They condemned Josephine Baker and her shows vociferously. In their warped mindset she was not only a symbol of the decadence they abhorred, she also epitomized the “racial impurity” they despised.

As nothing else, Kristallnacht crystallized her abhorrence of Hitler and all that he stood for.

With the Brownshirts then viewed largely as a lunatic fringe, Josephine proved more than able to counter their criticism. “I’m not immoral,” she objected, pithily, “I’m only natural.” With most in Germany, her tour had gone down a storm.

But when she returned two years later it would prove a very different story. Long before she got there, her detractors were ready. She travelled first to Austria, only to be greeted with screaming headlines—she was the ‘Black Devil’ and ‘Jezebel,’ the biblical female pariah and false prophet. Armed guards had to escort her through Vienna, as leaflets decried the “brazen-faced heathen dances” she would perform.

With many Austrians embracing the proposed union with Germany, Hitler’s rantings in Mein Kampf—including that black people were inferior “half apes”—had found a ready readership. The very worst coined the phrase negersmach to greet Ms. Baker, meaning that her performances and her very existence were an insult to the Nazi cause, and especially that of breeding the so-called Übermenschen, the much-vaunted Aryan master-race.

By the time Josephine’s show opened in Theater des Westens, one of Berlin’s most famous opera houses, the agitators were there in force, drowning her out with hoots and catcalls. A review the following day, in a pro-Nazi paper, screamed: “How dare they put our beautiful, blonde Lea Seidl with a Negress on the stage.” (Lea Seidl, an Austrian actress, had actually befriended Josephine and was mortified at how she was being treated). The show was scheduled to run for six months. It lasted three weeks, before Josephine—haunted, harangued, abused—was forced to flee.

Moving on to Dresden, the press decried the “convulsions of this colored girl.” In Munich, Josephine faced even worse. She was banned outright, for her performances would offend the city’s sense of self-respect, she was warned. She faced mobs who seemed to hate her and she sensed that they would like to see an end to her life. In truth her instincts—her palpable sense of the threat—were far from overblown.

Her Berlin tour had been booked by the Rotter brothers, who happened to be Jewish. Facing vitriolic criticism and denigration, they would be forced to flee to Czechoslovakia, leaving behind them the foremost Berlin theaters that they had run. Even there they were still not safe from the long arm of the Nazi state. Tracked by the Gestapo, the Rotter brothers would be hunted down, arrested and murdered.

After the shock of that tour, Josephine kept her distance from Germany and those other nations falling under Hitler’s sway, even as the dark horrors of Nazism suddenly grew clearer for all to see. On 9 November 1938, in a terror that foreshadowed the Holocaust, Kristallnacht—the Night of Broken Glass—convulsed Austria and Germany.

Jews were dragged from their homes and synagogues were put to the torch, as men, women and children were clubbed to death. Of course, by then Josephine was married to the wealthy Jewish industrialist Jean Lion, so she felt this horror most personally. As nothing else, Kristallnacht crystallized her abhorrence of Hitler and all that he stood for.

The coming conflict would bring her face-to-face with herself, as she “refused defeat.”

Ironically, this was the year that Josephine’s existence would come to Hitler’s attention most personally. Visiting Austria following the Anschluss—the takeover of that nation by Nazi Germany—the Führer chose to commandeer Vienna’s historic Weinzinger Hotel. Typically, he took the best suite for himself, having failed to notice before retiring to bed that none other than Josephine Baker’s portrait was gazing down at him from the wall. Needless to say, he was not best pleased.

By the time Jacques Abtey had come calling at Le Beau Chêne, Josephine was acutely aware of the need to stand up to bullies like Hitler and all he espoused. Nazi Germany’s actions were “criminal,” she would write and “criminals had to be punished.” As war engulfed Europe, she would declare herself willing to kill Nazis with her own hand, if the need arose. Of course, her recruitment as an Honourable Correspondent gave her the means to strike back, without necessarily ever needing to draw blood.

Josephine would become “emblematic of many things,” as Géraud Létang, of the Service Historique de la Défense, the Defense Historical Services of the French military, would declare: “of the engagement of women during the Second World War, of the engagement of foreigners in the French Resistance….” In truth, the coming conflict would bring her face-to-face with herself, as she “refused defeat,” requiring her to master the greatest performance of her life in which her very survival would hang in the balance.

But first, she would have to prove herself in the cut and thrust of espionage.

__________________________________

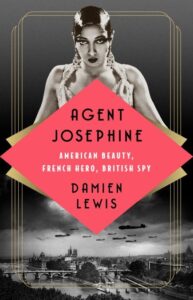

Excerpted from Agent Josephine: American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy by Damien Lewis. Copyright © 2022. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Damien Lewis

Damien Lewis is an award-winning writer who spent twenty years reporting from war, disaster, and conflict zones for the BBC and other global news organizations. He is the bestselling author of more than twenty books, many of which are being adapted into films or television series, including military history, thrillers, and several acclaimed memoirs about military working dogs. Lewis lives in Dorchester, England.