How Isaac Bashevis Singer Preserved European Jewish Life Through Literature

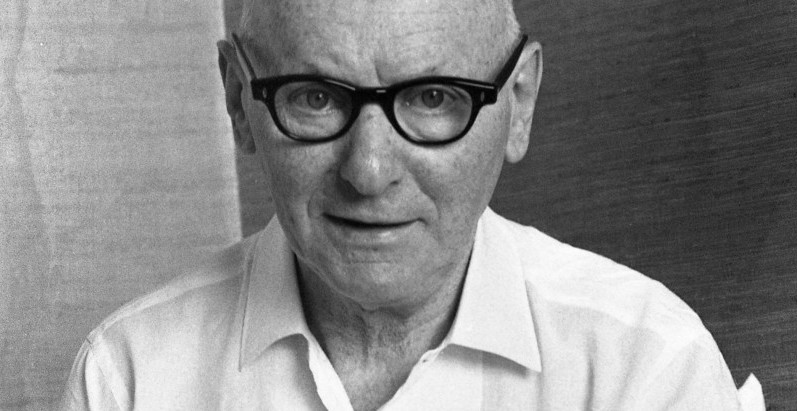

David Stromberg on the Artistic Vision of the Polish-Born American Nobel Laureate

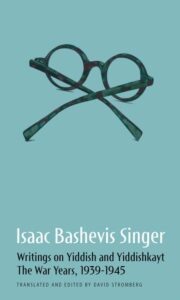

There has always been a gap between the English-language author Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Yiddish writer who published under at least three pseudonyms: Yitskhok Bashevis, Yitskhok Varshavski, and D. Segal. The publication of Singer’s wartime writings presents one of the first attempts to close that gap. Singer’s Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939-1945, the first of three volumes, covers the period between his first appearance as Yitskhok Varshavski in the Forverts—the world’s largest and most influential Yiddish daily—just months before the outbreak of World War II until the end of 1945, when Singer started publishing the Yiddish original of his first major literary memorial to the life of Jews in Poland, The Family Moskat. While the average Yiddish reader of the Forverts may not have known that Yitskhok Varshavski was Yitskhok Bashevis—the younger brother of Yiddish writers Esther Kreitman and Israel Joshua Singer—it is possible to imagine that same reader wondering about the identity of this “Isaac from Warsaw.” Whoever he was, he had a lot of opinions about the situation of the Jews in both Europe and the United States, before and during World War II, as well as the future of Jewish life in America. He was an unknown entity, but anyone reading his work could tell that he was deeply invested in his topic.

Singer’s writing during the period of World War II developed considerably, from pieces on various Jewish customs followed by Jews being targeted in Europe, to questions of how the Jewish spirit would survive the war. During those years, his own life also underwent radical changes. In 1939, his mother and younger brother, who remained in Poland after he and his older siblings had left, were sent by the Soviets in cattle cars to Jambyl, Kazakhstan, where they later died of illness and starvation, likely around 1942. His older sister survived the Nazi blitzes of London with her son, Maurice, and was struggling with mental health aggravated by the trauma of war. And his older brother, who had helped him immigrate to the United States and supported him during his first years, died of a heart attack in early 1944. His ex-lover, Runia Pontsh—who had given birth to Singer’s only son, Israel Zamir, in 1929—was expelled from the USSR by the Soviets and, after a sojourn in Istanbul, Turkey, settled in Palestine in 1938, where a few years later Zamir became a young member of Kibbutz Beit Alfa. Singer himself, in 1940, married a German-Jewish refugee, Alma Wassermann, who had fled with her husband and children from Munich, and who, after meeting him at a Catskills summer resort, began an affair that led to leaving her husband and starting a new life with the unknown Yiddish writer. In 1943, he became a citizen of the United States, solidifying his commitment to finding a path in literature as an American writer.

He wanted to get it all on record—not only the customs but also the immediacy of the loss that he realized was taking place at that very moment.

This biographical background is helpful in understanding the intensity of Singer’s writing during this time. The topics, while covering various aspects of Yiddish culture and Jewish life, are all infused with his personal perspective and experience at the time they were written. This makes his wartime writing fundamentally different from almost everything published to date—nearly thirty books for adults and more than fifteen for children in English translation alone. It opens a new phase in the translation and publication of Singer’s writing, exposing an immediacy and rawness that were, during his lifetime, mediated by the length of time that passed between the writing and translation of a given piece, as well as editorial and cultural concerns reflecting his contemporary American context. The gap between Singer’s Yiddish and English publications, which greatly influenced his decisions, is partly lifted, offering readers more direct access to his perspective on life in the old country from which he came, and the new country where he settled.

One of the most important aspects of this access is the chronological order in which the pieces have been organized. It is the usual practice, for authors who write in the language of the country in which they live, to publish their work in the order that it is written. But as an emigrant writer first publishing in Yiddish and much later translating his work into English, American readers were less often able to engage with Singer’s work chronologically. His first short story collection, Gimpel the Fool and Other Stories (1957), featured stories that were published, in order of appearance, in 1945, 1957, 1945, 1956, 1956, 1945, 1956, 1943, 1932, 1956, and 1943. Anyone trying to get a sense of Singer’s development as a writer from the arc of the stories as they appeared in the collection would go dizzy bouncing back and forth between the early 1940s and the mid-1950s, making a pit stop in the early 1930s, all without an inkling of what he wrote in between. This non-sequentiality lent a sense of mystery to Singer’s writing. But it did little to offer readers a coherent view of the author’s artistic vision.

Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt takes the opposite approach, following the order in which each article appeared in the Forverts. This offers readers a sense of how Singer’s thinking developed over time while grounding each one in its immediate context. The twenty-five pieces included in this volume were selected from a pool of over one hundred and fifty potential articles. These numbers make it clear that the selection is representative rather than comprehensive—an embarrassment of riches.

The articles vary across several themes connected to Jewish life and Yiddish culture, including history, customs, the influence of particular individuals, social tendencies, and critiques of the moment in which Singer was living and writing. The themes that emerge most tangibly during this period are the anger and anxiety that Singer felt over the apparent indifference of the Jewish sphere—including in the Yiddish world—over the cultural treasures that were in the process of being lost during World War II. Understanding his literary mission in the years during and after the Holocaust involves a reading of those concerns that he articulated during the time that it was actually taking place. It is no surprise, reading these pieces, that his first literary project after the end of the war was to write The Family Moskat, an epic novel about Jewish life in Poland. For him, Jewish life in the old country was not an abstract idea. It was a visceral loss, not only of the environment in which he grew up, but also of the two figures most directly associated with his own personal upbringing: his mother, who spent the most time raising him, and his older brother, who, in many senses, was the closest figure he had to a father.

These circumstances imbue Singer’s wartime writing with an intensely urgent tone. Singer did not have time to waste in writing the articles that he published during this period. He wanted to get it all on record—not only the customs but also the immediacy of the loss that he realized was taking place at that very moment. Knowing that a whole world, a whole way of life, a whole cultural treasure bound up with Yiddish and Yiddishkayt—knowing they were all going up in flames before his very eyes—this knowledge was crushing for Singer. It also drove him to put pen to paper and write.

__________________________________

From Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt, The War Years, 1939-1945. Edited and translated by David Stromberg. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with permission from White Goat Press.

David Stromberg

David Stromberg is a writer, translator, and literary scholar. His work has appeared in The American Scholar, Woven Tale Press, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. In his role as editor of the Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust he has published Old Truths and New Clichés (Princeton University Press), a collection of Singer’s essays, and a new translation of the canonical story Simple Gimpl: The Definitive Bilingual Edition (Restless Books). Among Stromberg’s recent writing is a series of speculative essays, including “A Short Inquiry into the End of the World” (The Massachusetts Review), “The Eternal Hope of the Wandering Jew” (The Hedgehog Review), and “To Kill an Intellectual” (The Fortnightly Review). He is based in Jerusalem.