How Indigenous Societies Fought to Preserve Their Blended Gender Identities in the Face of Colonialism

Gregory D. Smithers on Anticolonialism and Resistance to Binaries

When the Quechan people first encountered Spaniards in the mid-16th century, their homelands stretched from the Colorado River to the Gila.

The Quechan spoke a Yuman dialect and lived in small, patrilineal bands. These social ties developed over time into larger tribal groups known as rancherías comprising as many as five hundred people. By the mid-16th century, the Quechan had a history of fighting to preserve their collective identity and provide sustenance for the members of each ranchería. Balancing the subsistence needs of rancherías demanded that Quechans pay attention to the limits of local ecologies. One of the ways they did this was through a flexible system of gendered labor. Quechans lived with local ecosystems, paid attention to environmental changes, and noted fluctuations in the flow of rivers.

Binary distinctions—wilderness/civilization, male/female—had little utility in this ever-changing world. People needed to adapt to local ecosystems and embrace a fluid understanding of what it took to ensure the health of their respective communities. Rigidly prescribing which types of labor men and women must perform made little sense to the Quechans; instead, they fostered a dynamic worldview that empowered individuals to take on roles based on evolving skill sets, accomplishment, and communal need. Europeans didn’t appreciate this complexity. When they caught their first glimpses of Quechan society their reports suggested that men were employed in menial tasks that required greater physical strength, while people who took on a more feminine appearance engaged in skilled labor involving agriculture and the distribution of food.

Quechan life focused on community collaboration. Individual expression wasn’t frowned upon so long as it adhered to the protocols of reciprocity and balanced the needs of everyone who lived within the ranchería. Unlike the Spanish, Quechan people never developed a system of wealth accumulation like those encouraged by the individual or mission-operated encomiendas, a type of estate and system of forced labor in the Spanish settler colonies. An extensive network of trade routes connected communities, facilitating an exchange economy that supported life on the rancherías.

Within this social system Quechan people nurtured blended gender identities and formed intimate relationship that sometimes breached the heteronormative ideals that Europeans brought with them to the Americas. Marriage usually involved a monogamous relationship, although it was not unheard of for a man to have multiple partners. Marriage began with a proposal. The parents of the intended groom usually initiated marriage negotiations with the intended’s family, a process that often started shortly after a young woman had her first menses. A dowry was established, and gifts were distributed among the extended family.

Intimate social and sexual relationships in Quechan society also included kwe’rhame and elxa’ people. Male-bodied Quechans who took on women’s social roles and wore female clothing were known as kwe’rhame. Female-bodied people who assumed male social roles and dressed like men were known as elxa’. For both kwe’rhame and elxa’ people, the adoption of these identities in a Quechan ranchería was as much a spiritual as a physical experience.

Like scores of Native communities throughout the American West, Quechans placed great importance on dreams. Visions that foretold a person’s future path were viewed as spiritual messages. For people with gender-fluid identities, teenage dreams held particular importance. Dreams awakened young people to their special identity and, particularly for the elxa’, their considerable spiritual powers, which other Quechans both feared and respected.

When the missionary Fray Pedro Font arrived in Quechan territory, he found it difficult to see anything spiritually redeeming about kwe’rhame and elxa’ people. He saw only their physicality, and it struck him as strange—dangerously and sinfully so. Font claimed that he saw men who constantly stroked their penises in front of other men. He reprimanded these men.

They ignored Font and continued engaging in mutual masturbation. At other times, the kwe’rhame laughed at Font’s admonishment as they continued stroking their penises. Perhaps this was an act of anticolonial resistance. Font’s intrusiveness, like that of the Spanish more generally, was unwelcome to the point of being irritating. Little acts that got under the skin of these foreigners could form part of a larger arsenal of anticolonial resistance.

Binary distinctions—wilderness/civilization, male/female—had little utility in this ever-changing world. People needed to adapt to local ecosystems and embrace a fluid understanding of what it took to ensure the health of their respective communities.

That resistance boiled over in 1781. As the Anglo settler colonies in the East fought for, and ultimately won, their independence from the British, the Quechan fought their own battle for independence. Missionary intrusiveness in the lives of kwe’rhame and elxa’, and reports of Spanish men sexually assaulting Quechan women, resulted in the Quechans fast running out of patience with the Spanish.

The Spanish, though, remained committed to cementing their presence in Quechan territory. Under the leadership of Theodoro de Croix, the general commander of the Provinces of New Spain, two new permanent missions were slated for construction along the Colorado River. The missions aimed to undermine the behaviors that Font found so strange and to convert the Quechan to Catholicism. It was a form of cultural genocide designed to sever Quechan kinship bonds.

The Quechans knew the Spanish were up to no good. They recognized Spanish economic efforts to choke off their communities from exchange networks and complained about Spanish livestock trampling and destroying their crops. Font and other missionaries added to the growing aggravation by trying to change gendered and sexual behaviors that the Quechans saw as both normal and healthy. Relations grew increasingly fraught by 1779 and early 1780. As tensions rose, the Spanish deployed additional troops, effectively establishing “military colonies.”

Quechan people refused to be intimidated. In September 1780, de Croix received a warning from the frontlines. Written by Father Garcia, his words could not have been clearer: the Quechans, “already irritated by so many delays and evil influences . . . were becoming every day more restless and could not be controlled except by superior force.” Quechans rebuffed Spanish attempts to restructure their rancherías and rebuffed intrusions into their social life. Months earlier, in July, Quechan warriors had made their intentions clear when they launched a coordinated assault on the Spanish presence in Quechan territory. Quechan offensives against Spanish settlements continued during the summer of 1780, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of Spanish men, women, and children. The Catholic missions were not spared either. Quechan warriors clubbed four Franciscan priests to death and threw religious paraphernalia into the river. The Quechan message to the Spanish was unequivocal: leave.

Eventually the Spanish retreated. Quechan warriors had beaten the colonial invaders, and in the process cut off Spanish land routes to California. European colonizers returned years later, but for the moment the Quechans had won the space to renew their economic, social, and cultural lives. That included renewing the roles of kwe’rhame and elxa’ people in Quechan society.

The Quechan weren’t alone in trying to hold on to their cultural traditions and political autonomy in the face of growing settler intrusions. In California, the Pacific Northwest, the Arctic, and the sub-Arctic, Indigenous communities continually renewed their traditions. Across this diverse region some Native communities retained a place for gender fluidity in their social structures. Non-Indigenous traders, politicians, missionaries, and anthropologists observed the existence of people with gender-fluid roles and identities. The bulk of these observations were made by anthropological fieldworkers from the late 19th century, so caution is needed when reading the labels they used. Over time, the meaning of a word or phrase changes, and usage adapts to new social contexts. Additionally, Indigenous people may decide to resist unwanted questions from outsiders. They can do this by refusing to answer questions deemed overly intrusive, or by giving an answer that conceals the deeper meaning of a word, phrase, or cultural practice.

The result is a contest over meaning that reverberates into our own times. Between the late 18th and early 20th century, scholars, missionaries, traders, settlers, and government officials in the Americas, Europe, and Asia interpreted Indigenous cultural self-preservation as further proof of “Aboriginal” secretiveness and untrustworthiness. Ethnological descriptions of Siberian shamans as sexless, asexual, or given to “perversions”—namely, “transvestitism” and “homosexuality”—further reveal the wild speculations that ethnographic writers indulged in. The invention of this body of knowledge informed empirical fictions about Indigenous people. It was a knowledge system shaped by a revolution in European thought during the Enlightenment of the 18th century. Its logics trickled down from an elite few. When applied to the Americas, the enlightened few offered up generalizations about Indigenous communities that were based on scattered assumptions and half-truths.

Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment systems of colonial knowledge placed Indigenous people in fixed, transhistorical categories. They willfully obscured a reality of cultural dynamism and physical movement in a bid to contain, control, and, if necessary, destroy Native people. For example, non-Indigenous linguists attempted to corral gendered pronouns and impose some sort of order on Indigenous cultures. These intellectual labors were in keeping with the empirical thrust of the Western intellectual tradition. In contrast, Native communities operated in worlds in which metaphor and mnemonic devices reminded people of the importance of adaptation and renewal to ensure balance in the overlapping worlds of the physical and the spiritual.

To underscore this point we can use the work of linguists and ethnographers to challenge their own assumptions and reveal dynamic worlds constantly in motion. The Koryak story of how Raven became a woman illustrates this perfectly. The Koryak, whose homelands are located in the present-day Far East of Russia, tell of a time when Quikinnaqu (Big Raven) decided to turn himself into a woman by cutting off his penis. Quikinnaqu turned his penis into a needle case, his testicles into a thimble, and his scrotum into a workbag.

Quikinnaqu thereafter moved to a camp named Chukchee (or Chukchi). Here Quikinnaqu lived for some time, refusing the overtures of young men who offered to make Quikinnaqu their wife. But one day Quikinnaqu met Miti, a woman who had run out of food. Miti needed to adapt to her sudden hardship. She dressed as a man and refashioned her stone maul into a penis. Miti then headed off with a team of reindeer and eventually stopped at Chukchee. A short time passed before the people of Chukchee noticed that Miti worked hard and should have a partner—Raven.

Raven and Miti had changed gender roles prior to their meeting. How should they act toward each other? They debated the question and eventually decided to return to their previous form. They swapped clothes, and in time Raven’s penis and testicles grew back.

Native people retained and renewed dynamic storytelling traditions. They did this by retelling stories at the same time and in the same location during the ceremonial cycle. Native knowledge keepers repeated ceremonial practices to ensure the accuracy of their sacred stories and to highlight important morals. In the case of Raven and Miti, the story emphasizes the rebalancing of life. To accomplish their new state of balance Raven and Miti not only moved back and forth along a male-female gender continuum but openly traveled along the gender spectrum in ways that fit their changing circumstances.

Traveling east from Koryak homelands and across the Bering Strait, Yup’ik-speaking people maintained social structures that also included gender-fluid people. On St. Lawrence Island, just south of the Bering Strait, and into what is today Alaska, Yup’ik terms for gender fluidity survived Russian, British, Spanish, and American colonial incursions. However, disentangling Indigenous terms from Eurocentric interpretations and ethnographic studies remains a challenge to any effort to decolonize Native kinship terminology and reclaim gendered traditions.

In Siberia, the Russian Far East, western Alaska, and southern Alaska, the Yup’ikterm uktasik has been interpreted by non-Indigenous scholars as meaning “soft man” or “womanly man.” Anthropologists have ascribed other Yup’ik terms, like aranu’tiq and anasik, to gender-fluid people in Alaska. As valuable as this language is today, they captured meaning at a particular moment and place in time in the past (and to the extent that Native informants felt comfortable sharing these terms). More challenging is the process of peeling back the cultural filters used in ethnological writing to understand Native cultures and how they change over time.

This challenge becomes even clearer as we move south along the Pacific coastline and into Tlingit communities. Tlingit kinship communities are matrilineal and traditionally included shamans with spiritual powers so great that they could compel a couple to have sexual intercourse. These types of beliefs and practices troubled outsiders—from 18th-century missionaries to early twentieth-century psychoanalysts—and were labeled everything from strange to superstitious.

But in Tlingit society, shamans and other medicine people played important roles in ensuring the health and balance of society. When non-Indigenous outsiders asked Tlingit people about shamans and medicine people, they sometimes referred to a small group of people known as gatxans. Gatxans reportedly had fluid gender identities. Europeans knew them as “half-men, half-women.” Tlingits reportedly believed that gatxans possessed spiritual powers and routinely reincarnated themselves. In some cases, gatxans engaged in “homosexual” relationships, although the anthropological record tends to overstate this point. Very little oral or written evidence survives to illuminate how both Tlingits and colonizers viewed the gatxan during the late 1700s and early 1800s, but we have clues. Anthropologists provide one clue: a definition of gatxans as “cowards.”

I’ve uncovered no historical evidence to suggest that Tlingit people viewed gatxans as cowards during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. That’s not surprising, given that the traders, soldiers, and scientists who interacted with the Tlingit weren’t focused on deep historical analysis of gender identities or sexual habits among Indigenous people. These outsiders had other objectives, specifically, making money by extracting resources and expanding trade networks. Still, it’s possible to trace the outlines of gender and sexual traditions in this region by examining a variety of sources from both Tlingit history and that of their Indigenous neighbors.

The Tlingits’ northern neighbors, the Kaska people of the subarctic region, included women who took on male roles or assumed positions of leadership; one of these was “Nahanni Chief,” whom early-19th-century fur traders described as “cunning.” As with other Athapaskan-speaking people, who forged kinship communities from the subarctic to the Southwest of North America, gender fluidity constituted an important facet of life. Contrary to the opinions of fur traders, there was nothing deceptive about fluid gender identities. Individuals within Kaska society maintained their focus on balancing the needs of local bands and extended family networks.

But what of the gatxan? Did gender fluidity feature in their everyday life, as it did for the Kaska? And what of the association of gatxans with the word “coward”? In early 18th-century Anglo-American usage, a coward was “one that has no heart, or Courage.” They are “cow-hearted” and were represented on a coat of arms as a lion with its tail between its legs. During the later decades of the 18th century and the opening of the 19th, a coward was defined in more strident, judgmental terms. A coward was timid (a “poltroon”), “a wretch whose predominant passion is fear,” and, according to Noah Webster’s 1817 dictionary for school children, “one who wants courage.”

These definitions are at odds with the ethnographic source that originally associated gatxan with the word “coward.” That association dates back to John Swanton’s 1909 book Tlingit Myths and Texts. In this ethnological work, written for the Smithsonian Institution, Swanton refers to a story that he recorded in Sitka, Alaska, about a man named Coward (Q!atxa’n). As Swanton relates the story, Coward volunteers to travel into a valley with a figure known as Wolverine-Man (Nu’sgu-qu). Wolverine-Man gives Coward instructions on how to construct a trap to capture groundhogs. After some initial setbacks, Coward successfully captures some groundhogs and trades their skins—skills that help him become exceptionally wealthy.

There’s nothing in this story that conforms with Anglo-American definitions of a coward or cowardice. The translation of Q!atxa’n as “Coward” (and the uncritical acceptance of this definition) is curious in light of Q!atxa’n’s heading off into an unknown valley, becoming adept at hunting, demonstrating ingenuity, and being enterprising enough to recognize non-Indigenous people who are willing to purchase the skins he’s accumulated. Q!atxa’n is the antithesis of a coward.

Still, words have power, and as in much of the material in written historical and anthropological records about Native America, misinformation and misinterpretation conceal deeper truths. This certainly appears true for non-Indigenous interpretations of Tlingit culture. For much of the twentieth century, social scientists combed through old accounts written by fur traders, soldiers, or missionaries, and relied on oral testimonies from the few informants they met during fieldwork trips.

This research elicited a variety of stories about “Coward” being a captive of war forced to wear women’s clothing, or the gatxan acting like a woman but not necessarily wearing women’s clothing. The different stories are suggestive of the adaptiveness of Native oral traditions and a desire to protect proprietary information from the uninitiated—specifically, non-Native anthropologists and psychologists. They also raise questions about non-Indigenous fieldworkers’ impact on oral responses and the interpretative limitations of social scientific methodologies.

Undeterred, social scientists lumped gatxans into homogenizing categories like “berdache,” “homosexual,” or “transvestite.” These labels, inventions of the post-1870s Western world, expanded on 18th-and 19th-century cultural assumptions about certain types of character traits and how those qualities applied to Native Americans. This was (and is) how the cultures of colonialism buttressed the economic, political, and military manifestations of settler imperialism.

_____________________________________________________

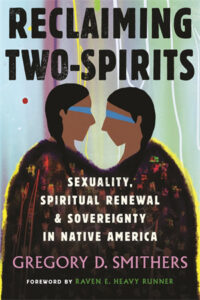

Excerpted from Reclaiming Two-Spirits: Sexuality, Spiritual Renewal & Sovereignty in Native America by Gregory D. Smithers (Beacon Press, 2022). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Gregory D. Smithers

Gregory D. Smithers is professor of American history and Eminent Scholar at Virginia Commonwealth University and a British Academy Global Professor at the University of Hull in England. His research focuses on Cherokee and Southeastern Indigenous history, as well as gender, sexuality, racial and environmental history. His books include Native Southerners: Indigenous History from Origins to Removal and The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity. Reclaiming Two Spirits: Sexuality, Spiritual Renewal & Sovereignty in Native America is his latest book. Follow him at gregorysmithers.com and on Twitter (@GD_Smithers).