How Ida B. Wells Brought the Truth About Lynching to National Attention

Alex Tresniowski on the Speech that Changed the Journalist-Activist's Life

October 5, 1892

Lyric Hall, New York City

Ida Wells tried hard not to cry. A thousand miles from home, largely friendless in a strange new city, she stood in front of hundreds of people and felt the tears coming on, and she tried to fight them off. But they came anyway—tears of loss and loneliness.

Five months earlier, a mob of white men demolished the offices of her newspaper, Free Speech, in Memphis. Wells fled to Brooklyn, New York, a sprawling city unlike any small southern town she had known. She lived by herself in a rented apartment on Gold Street, in a mostly residential neighborhood called Vinegar Hill, more commonly known as Irishtown, wedged between the Brooklyn Bridge and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. There she lived under the threat “of hanging or burning at the stake,” the Boston Herald declared, should she ever dare return to her home in Memphis. Wells was thirty years old.

The same month Wells left Memphis for Brooklyn, May 1892, her friend T. Thomas Fortune offered her a weekly column in his newspaper, the New York Age. Wells took the job, she would say, with a new sense of purpose and resolve. “Having lost my paper, had a price put on my life and been made an exile from my home for hinting at the truth,” Wells wrote, “I felt that I owed it to myself and to my race to tell the whole truth now that I was where I could do so freely.”

Her first article for the Age ran across seven columns, covering nearly the entire front page of the June 25, 1892, issue. It was titled “The Truth About Lynching.” It was, in a way, a continuation of the antilynching article that led to the destruction of the Free Speech offices in Memphis, except that it was, as Wells had promised, a fuller, freer, and more graphic denunciation of the racism, terror, and violence inflicted on the colored race in the South.

It was unlike anything ever written by a Black journalist before.

Wells set out to do two things: debunk the accepted premise used to justify lynching—the rape of white women by Black men—and vividly describe the true horrors of lynching in a way that would change perception of the practice. “It is with no pleasure I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed,” she wrote. “Somebody must show that the Afro-America race is more sinned upon than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.”

Wells did not hold back. She listed more than seven hundred instances of lynching, and provided the dates, places, and names of victims—“the awful death-roll that Judge Lynch is calling every week.” She described the barbaric sameness of many of the crimes—white mobs dragging Black men out of jail cells; brutal hangings in town squares; already-murdered victims riddled with bullets or dismembered. “The flaying alive of a man in Kentucky, the burning of one in Arkansas, the hanging of a 15-year-old girl in Louisiana . . . until the dark and bloody record of the South shows 728 Afro-Americans lynched during the past eight years,” she wrote.

“Somebody must show that the Afro-America race is more sinned upon than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.”

Of those victims, Wells noted, only a third had even been accused of rape; the rest were lynched under a variety of other justifications, including, in one instance, “acting sassy.” Of those charged with rape, Wells insisted most were surely innocent. “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women,” she argued. She insisted here as she had before that the charge of rape, therefore, was largely a pretense—the real aim of lynching was to keep the Black race economically subjugated through the use of terror and violence. The lynching of her close Memphis friend, Thomas Moss, had, after all, been precipitated by an economic clash—Moss’s Black-owned grocery posed a threat to a rival white-owned store. In the end, Moss’s lynching led to the destruction of his store, and to its stock and customers being absorbed by the very rival who saw to it that Moss was lynched.

Wells assembled a uniquely vivid, factual, and coherent portrait of the practice in America—the first fully contextualized analysis of lynching, and of the willful indifference of white law authorities to it, as seen from the side of the victims.

Wells believed the same was true of most acts of mob violence against Blacks across the country. The white southerner, she wrote in her autobiography, “had never gotten over his resentment that the Negro was no longer his plaything, his servant, his source of income.” Without the practice of slavery to keep Black citizens under their control, white southerners instead branded the Negro as a race of wild rapists—people who needed to be brutalized in order to be tolerated. By so thoroughly and graphically cataloging the reality of lynching throughout the South, Wells, for the first time, provided a solid factual argument against the foundational lie that justified the practice.

And because Wells anticipated a backlash that would suggest she’d exaggerated or fabricated her descriptions of lynching, she did something shrewd—she used only white sources for her catalog of crimes. All her information came from white journalists and white-owned newspapers, and if she made a personal observation, she backed it up with secondary reporting. These are known facts, Wells was saying—all she had done was compile them into an unspeakable whole.

Wells’s approach to the topic helped elevate the New York Age article from daring journalism to something larger and more profound. Wells’s antilynching statement would go on to become, according to the author and professor Anita August, “the founding rhetorical text in the anti-lynching movement.” Wells assembled a uniquely vivid, factual, and coherent portrait of the practice in America—the first fully contextualized analysis of lynching, and of the willful indifference of white law authorities to it, as seen from the side of the victims.

That, on its own, ensured her article’s impact. But that was not all Wells did. Despite avoiding sentimentality, she also managed to invest her writing with a deep and undeniable humanity, a beseeching demand for reason and decency. “The Truth About Lynching” was a moral clarifier, a call to action, so persuasive it could not be dismissed. Wells did not hope to reflect public opinion—she meant to shape it.

T. Thomas Fortune printed ten thousand copies of the June 25 issue of the New York Age and sent them out across the country. More than one thousand copies were sold in Memphis alone. These were not staggering numbers (Black newspapers like the Age had limited circulation) but they were signs Wells now had her largest audience yet.

The article, which carried the byline “Exiled,” did produce a predictable backlash against Wells. One Boston newspaper editorial called her “a licentious defamer of Southern women” and “a harlot,” while the governor of Virginia and former Confederate colonel Charles T. O’Ferrall said “the slandering utterances of Ida Wells are calculated to do harm rather than good, and intensify rather than mollify the spirit of violence.” O’Ferrall argued that the crime of Black men raping white women “caused all the lynching in the South, with rare exceptions,” and that Wells and other Blacks should “frown down upon it and cry out against it, and not exert their energies to a denunciation of the lynching.”

But, crucially, Wells’s article also made it into the hands of one of the most prominent Black women in Brooklyn—an accomplished schoolteacher and activist named Maritcha Remond Lyons.

Lyons began teaching in 1869, the same year she became the first Black girl to graduate from Providence High School in Rhode Island. Over the years Lyons gained, as she put it, “some little recognition as an elocutionist”—a public speaker whose powerful voice could reach the highest rafters. Lyons met Ida Wells through the Brooklyn Literary Union, one of the leading literary clubs in the city. The Union held its meetings at the Everett Assembly Rooms on Willoughby Street, in halls rented out for twenty dollars an evening. In one of the Union’s featured debates, Lyons squared off with the club’s invited guest, Ida Wells. Lyons later wrote that her own performance “won the plaudits of the members.”

Wells did not hope to reflect public opinion—she meant to shape it.

As for Wells, her performance in the debate gained her a lifelong friend in Lyons. Fourteen years older than Wells, Lyons was impressed by Wells’s “grit and determination,” and agreed to “coach her in the art of extempore speaking.” Lyons taught Wells her two main rules of public oratory: “1 – Be so familiar with your subject that you are literally saturated with it; think, meditate and reflect to develop all the points in logical sequence. 2 – Learn how to manage the voice; if thought is prolific, expression of ideas will become automatic.”

Not long after the debate, Lyons received her copy of the New York Age that featured “The Truth About Lynching.” The article had its desired effect—it moved Lyons to action. Together with Victoria Earle Matthews, a journalist and early reformer in Brooklyn’s Black settlements, Lyons arranged local meetings to read and discuss Wells’s writings, and in the following weeks the meetings grew in size. Matthews and Lyons decided they wanted to help Wells financially—and perhaps even raise enough money to allow her to publish the Free Speech again. They organized a committee of 250 women, announced an event in honor of Wells, and invited her to give a speech to their expanding circle.

Wells agreed to attend, and a date and place were picked—October 5, 1892, at New York City’s Lyric Hall, an elegant dance palace that normally hosted wedding receptions and society balls.

*

On the evening of October 5, 1892, Wells crossed the Brooklyn Bridge—free for walkers, three cents for drivers—and headed north toward the Manhattan neighborhood known as Longacre Square.

Around her, the city was rising. In lower Manhattan, the new emigrant office at Ellis Island was now processing the many millions of immigrants streaming into the city each year. A mile inland from the harbor, Joseph Pulitzer had just finished constructing the world’s tallest office building—his golden-domed, 26-story World Building on Park Row. Farther north, the stately, marble, 77-foot Washington Square Arch, flanking the south end of Fifth Avenue, had just been completed. “Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair,” read the inscription atop the arch. “The event is in the hand of God.”

Wells made her way north to 42nd Street, the wide thoroughfare that spanned the island from the East River to the Hudson River. The street was anchored on Fifth Avenue by the massive, aboveground Croton Reservoir, a stone fortress with walls that were 50 feet tall and 25 feet thick, built to hold more than 20 million gallons of pure water piped down from the Croton River 45 miles upstate.

One block west of the Reservoir, between 42nd and 43rd Streets on Sixth Avenue, sat Lyric Hall.

Ida Wells walked past newsboys and pretzel vendors and entered the hall, and once inside she was surprised by what she found. Matthews and Lyons had gone to some lengths to prepare the hall for her speech. Behind a large main platform, a string of lights spelled out IOLA, Wells’s pen name. The evening’s programs were designed to look like miniature copies of the Free Speech. The hall was filled with “the leading colored women” of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, Wells noted—“a brilliant array.” The event, Matthews and Lyons declared, “was the greatest demonstration ever attempted by race women for one of their number.”

Matthews began the program with an introduction. Then a few short speeches and the reading of resolutions, followed by music and singing. Finally, Ida Wells took the stage. Matthews, Lyons, and several other prominent activists took their chairs behind her on the platform, and in front of her a crowd of several hundred sat and waited. Wells looked out over their faces, took a deep breath, and began to tell her story. And then, as she would recall, “a panic seized me.”

*

Wells was not yet a confident speaker. She’d stood before people and spoken before, first in school, then in recitals and plays. She was comfortable going door-to-door and giving short speeches to sell newspaper subscriptions. She’d even addressed respectable gatherings: in 1891, she talked about her life in front of the Afro-American League in Knoxville, Tennessee, and in September 1892 she gave a speech titled “The Afro-American in Literature” to a literary circle in the Concord Baptist Church of Christ in Brooklyn. She also had the benefit of Maritcha Lyons’s public speaking lessons.

Even so, Wells admitted, “When the committee told me I had to speak, I was frightened.” Her speech at Lyric Hall would be different from anything she’d ever done. It was expressly political, and it was at the request of—and in the presence of—her most prominent fellow activists.

“This was the first time I had ever been called on to deliver an honest-to-goodness address,” Wells wrote—the first time she’d actually written down the words of a speech, rather than simply speaking from memory. Wells was being asked to transform herself yet again, from a journalist into a bona fide public speaker—someone who could not only command a crowd, but also stir it to action.

Wells also understood that, as part of her speech, she would have to discuss the violent lynching of her Memphis friend Thomas Moss, a trauma that was only a few months old. She had no idea how talking about Moss would affect her. And, to her surprise, it overwhelmed her.

Onstage at Lyric Hall, not too far into her speech, Wells lost her focus. While describing the events surrounding Moss’s murder, “my mind went back to the scenes of the struggle, to the thoughts of my friends who were scattered throughout the country,” Wells later wrote. She felt shaken by “a feeling of loneliness and homesickness for the days and the friends that were gone.” And then, she said, “I felt the tears coming.”

She spoke of the loss of the three young men—of her friends—in starkly human terms.

Wells struggled to control her emotions, or at least prevent the prominent people behind her from seeing her cry. “I was afraid that I was going to make a scene and spoil all those dear good women had done for me,” she wrote. “I kept saying to myself that whatever happened I must not break down, and so I kept on reading.” But Wells could not stop her tears—and she realized she didn’t have the handkerchief she usually carried with her. She’d left it on a seat behind her.

Wells did not stop speaking. Instead, she put her hand behind her back and signaled for help. Victoria Matthews came forward, and Wells asked for her handkerchief. Matthews got it and brought it up to her. “I wiped my nose and streaming face,” Wells wrote, “but I kept on reading the story which they had come to hear.”

It was without doubt a powerful story. “On the morning of March 9, the bodies of three of our best young men were found in an old field, horribly shot to pieces,” Wells said in her clear, even voice, even as tears still ran down her face. The details of the killings, and the dispute that led to them, were dramatic enough, but Wells, who was friends with Moss’s widow and godmother to his daughter, also spoke of events and moments that could not be found in newspaper accounts. She spoke of the loss of the three young men—of her friends—in starkly human terms.

“The baby daughter of Tom Moss,” Wells said, “too young to express how she missed her father, toddles to the wardrobe, seizes the legs of the trousers of his letter-carrier uniform, hugs and kisses them with evident delight, and stretches up her little hands to be taken up into the arms which will nevermore clasp his daughter’s form.

“And his wife holds Thomas Moss Jr. in her arms, upon whose unconscious baby face the tears fall thick and fast when she is thinking of the sad fate of the father he will never see, and of the two helpless children who cling to her for support she cannot give.”

Many people in Lyric Hall quietly wept. “Do you ask a remedy?” Wells said at the end of her speech. “A public sentiment strong against lawlessness must be aroused. Every individual can contribute to this awakening. When a sentiment against lynch law strong, deep and mighty as that roused against slavery prevails, I have no fear of the result.

“The voice of the people,” Well concluded, “is the voice of God.”

*

When she was finished speaking, Wells felt mortified. “I had not been able to prevent such an exhibition of weakness,” she later wrote. In fact, her speech was a success. The crowd gave her a long, loud ovation, and afterward several people assured her that her emotions had only lent her words more drama and power. One preacher told Wells her speech “did more to convince cynical and selfish New York of the seriousness of the lynching situation than anything else could have done.” One newspaper account of the speech read “All eyes were turned on Ida B. Wells, for it was she herself a victim of the portrayed outrages, and she was moved to grief. Miss Wells was the star of the convention; though modest in appearance she shone with intellectual brilliancy.”

Wells’s speech at Lyric Hall changed her life again. She gained an almost instant renown as a fiery activist and forceful public speaker, giving her the platform she needed to spread her antilynching message. The event raised four hundred dollars, which was handed to Wells, along with another one hundred dollars, to use toward publishing her New York Age editorial as a stand-alone pamphlet that could be more easily distributed around the country. Her new friends Maritcha Lyons and Victoria Matthews also presented Wells with a gold brooch in the shape of a pen. The brooch had the word mizphah etched on it.

Mizphah is the Hebrew word for “lookout” or “watchtower.”

It was a sort of benediction. The expanding circle of Black New York–area activists had appointed Ida Wells their lookout, their eyes and ears—the tip of their spear in the fight for the rights of Black citizens.

Wells continued to inspire the movement through her writings and through many more powerful speeches—hundreds of them over the next several years. Some women’s clubs even chose to name themselves after Ida Wells. Her influence on the movement led directly to the formation of the National Association of Colored Women Club, which helped to clear a path for the eventual founding, in 1909, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People—the NAACP.

The next three years were a nonstop storm of action and advocacy for Ida Wells. With the money raised by her Lyric Hall speech, Wells and T. Thomas Fortune published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, a pamphlet that featured pages of lynching statistics and more of Wells’s powerful, graphic narrative about the true nature of mob violence.

The pamphlet sold for 15 cents, and found readers across the country. Wells followed it up in 1895 with another even bolder pamphlet, The Red Record, which ran to one hundred pages and delivered more vivid reporting about the rising tide of lynchings in the United States. The pamphlets were financially successful and earned Wells more fame as the leading female activist of her time. “The salvation of the colored people of the south,” read one editorial, “may yet come through a woman.” Wells was becoming, in the words of another columnist, “the most famous colored woman in the world.”

*

In 1894, more than one hundred people, a surprising number of them white, crowded into the main pews and balcony seats of the Bethel A.M.E. Church, an ornate, Gothic Revival building with towering arched windows overlooking Sullivan Street, in New York City’s Tenderloin district. They were there to hear Ida Wells speak.

Her friend T. Thomas Fortune introduced her to the congregants, before Wells—wearing a plain Black dress with her mizphah gold brooch, and a white braided leghorn hat pinned with white ostrich feathers—strode forward and stood confidently before the gilded, wood-paneled altar and the church’s large silver crucifix. By then Wells had delivered more than one hundred public speeches on the subject of lynching, including several speeches in the United Kingdom, where she had been invited for a series of talks.

“The colored people of this country should organize themselves from one end of the country to the other,” Wells told her listeners in the church, her plea for action now sharpened into a militaristic charge. “They should at least contribute the sinews of war with which to fight the battle. It is our duty to see that every story published from the South, in which a Negro is accused of some fiendish act and lynched for it, is run down by our own detectives. There are two sides to every lynching.”

Every story. Every accused Black man. Every last one. This was the task Wells set for herself, and for her race. They would all be detectives now, searching for truth and justice, no matter the cost or danger.

“I am occasionally threatened to this day with death if I do not cease my work against lynching,” Wells told one reporter in 1895.

“Does it scare you any?” the reporter asked.

Wells closed her eyes, took a moment, and smiled.

“I haven’t quit yet,” she said.

____________________________________________

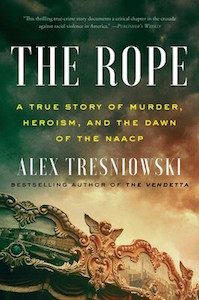

From The Rope: A True Story of Murder, Heroism, and the Dawn of the NAACP. Used with the permission of the publisher, 37 Ink. Copyright © 2021 by Alex Tresniowski.

Alex Tresniowski

Alex Tresniowski is a writer who lives and works in New York. He was a writer for both Time and People magazines, handling mostly human-interest stories. He is the author or coauthor of more than twenty books, including the 2005 true-crime thriller The Vendetta, which was used as a basis for the 2009 Johnny Depp movie Public Enemies. The Rope is his latest book. For more about this story and the author, please visit AlexTres.com.