Ian McKellen owes an extraordinary debt to Ronald—or J.R.R.—Tolkien. With Shakespeare’s bust on display in his riverside home, he rhapsodizes often over the bard’s greatness, and what everyone owes him, and he is truthful and eloquent about Shakespeare the man. He lavishes praise on other writers from Chekhov to Martin Sherman, yet when he entertains any number of guests with unbounded generosity in restaurants, at the end of the lunch or dinner party he rises to his feet, looks around benignly grinning at everyone, and addresses the company with the words, “Gandalf pays!”

At the very age when Margery’s illness had been casting and deepening that lasting shadow over her son’s life in Bolton, an Oxford professor of medieval literature was putting the final touches to his epic depiction of the timeless wizard. This was destined, more than anything else, to take the Bolton Grammar School boy into unimagined realms of fame and gold, far beyond any conceivable ambition he or his family might have.

The parallels between Ian’s life and that of Gandalf ’s creator are extraordinary. Humphrey Carpenter, a writer who lived in Oxford, met J. R. R. Tolkien in 1967, calling on him at Sandfield Road in Headington, his ordinary suburban home, which W. H. Auden once called “hideous.” In his biography of Tolkien, Carpenter’s first-hand description of the creator of Ian’s most famous role has a striking similarity to McKellen. He found Tolkien had what we can identify as the same strange voice, deep but not without resonance, entirely English but with some quality he could not quite put his finger on, as if he had come from another age or civilization . . . “[While] he does not speak clearly . . . He speaks in complex sentences.”

This description eerily fits Gandalf and Ian McKellen, as well as Tolkien. Perhaps by his 76th year, when Carpenter visited Tolkien, he had grown into this unearthly figure. Carpenter was clearly out of his depth when he talked to him, for he believed some strange spirit had “taken on the guise of an elderly professor.” He had completed The Lord of the Rings nearly 20 years before.

There is much more than the voice. Tolkien was born on January 3, 1892, and a month later, in Bloemfontein Cathedral, South Africa, christened John Ronald Reuel. He once said he sometimes did not feel this to be his real name. At the age of three Tolkien suffered a bout of rheumatic fever in Pretoria. Ian McKellen had also been three when he caught diphtheria, which some claim resulted in the highly idiosyncratic tone of voice that so colors his performances.

Arthur, Tolkien’s father, a bank manager, suffered a severe hemorrhage and died when he was four years old, during a time when he and his mother were visiting Birmingham (where both parental families had homes). Mabel, his mother, who had no great love of South Africa, brought Ronald and his brother Hilary up in Birmingham, and it was here his now widowed mother, in the course of her devout Catholic practice, befriended Father Francis Morgan, an Oratory teacher, who became protector and mentor to her two sons. In 1904 when Ronald was 12, Mabel was diagnosed with diabetes and died the same year.

Tolkien felt his “own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us Ian McKellen a mother who killed herself with labor and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.” In 1949 when Ian was ten, his mother Margery had been taken into hospital with breast cancer. She died in 1951. Ian, was 12, exactly the same age as Tolkien when his mother died.

In McKellen’s case the theatre substituted for religion.Ronald was a cheerful, almost irrepressible person with a zest for life. He loved good talk and physical activity like the Hobbits he created. He had a deep sense of humor and a great capacity for making friends. But from now on there developed a second side, more private but predominant in his diaries and letters. This side was capable of bouts of profound despair. More precisely, and more closely related to his mother’s death, when he was in the mood he had a deep sense of impending loss. Nothing was safe. Nothing would last. No battle could be won for ever.

Father Morgan became Tolkien’s sole guardian, a kind and generous benefactor. Ian’s father Denis, who as a pianist had some inclination of an artist, was the borough engineer of Bolton, and to his son had been a remote, unapproachable figure. Ian had no place to channel his grief or even share it, although he had been very close to his mother. Denis and his son had little rapport, and Ian, mourning in an unexpressed and even secret way, had grown somewhat lonely and into himself.

While Ronald channelled that emotion of loss into religion, which provided an outlet, Ian’s emotion had become less specific, more widespread and directed more towards glamour and entertainment than liturgy and language, the spoken versus the written word. Carpenter claims his mother’s death made Tolkien into two people and that his faith took the place in his affections that Mabel had previously occupied. This may be particularly pertinent to McKellen and may even be put forward as an accurate description of his personality. Two people to start with in life. In McKellen’s case the theatre substituted for religion.

A romantic disposition towards women and especially towards Edith Bratt, his first girlfriend, daughter of a single mother, whom Ronald met when he was 16 and she 19, remained with Tolkien all his life. Their love survived early years of separation, while Edith, “remarkably pretty, small and slim,” remained his ideal, his inspiration for the female characters in The Lord of the Rings. Father Morgan forbade Ronald to write to her, or to see her until she was 21. He gave in finally and married them in 1916. From the start, it was not an easy marriage, and although blessed with four children, Tolkien found domestic concerns rather irritating and trivial.

Yet “I feel on my own, a bit of an orphan,” McKellen confessed on the BBC program Who Do You Think You Are? This was equally true of Tolkien, although dragons and mythological beings were for him what fictional characters were for Ian.

If the similarity of background between McKellen and Tolkien in some ways prepared him for Gandalf, the role still almost never happened for him. Dozens of actors were considered, while Christopher Plummer and Sean Connery, better known film stars, were offered the part before him. Richard Harris was another early possibility but declined, although Ian said he read for the part. Plummer said, of going on the lengthy filming schedule proposed in New Zealand, “I thought there were other countries I’d like to visit before I croak.” He later regretted turning it down. That’s why, he said in jest, “I hate that son of a bitch Ian McKellen!”

Connery revealed only recently his refusal to do it came down to the fact he “never understood the script.” He added, “I read the book. I read the script. I saw the movies. Ian McKellen, I believe, is marvelous in it.” Connery was to be paid six million dollars and, or so it was reported, 25 per cent of the gross, which came to nine billion. In 2005, again Connery told the New Zealand Herald: “Yeah, well, I never understood it . . . I saw the movie. I still didn’t understand it. I would be interested in doing something that I didn’t fully understand, but not for 18 months.”

If the similarity of background between McKellen and Tolkien in some ways prepared him for Gandalf, the role still almost never happened for him.Even before the casting of Gandalf, there was a bizarre circumstance affecting whether or not McKellen could do it. I have quoted as an epigraph Ian’s remark that no actor was ever first choice, but in fact he actually was the director John Woo’s first choice for the role of Swanbeck in Mission: Impossible 2 (the 2000 film). He turned it down because he was not shown the script first. If he had persisted and accepted to play Swanbeck, which Anthony Hopkins then played, he would never have been Gandalf.

Ian claims he never read The Lord of the Rings before he signed up for it. For Gandalf he was offered four million pounds. But it was more likely that in his sensible practical way, he considered the role in script form more relevant to his taking part. Asked about why he was offered the role, he says that he was pretty certain Peter Jackson had offered it to Sean Connery and even Anthony Hopkins before offering it to him. He added that, personally, his first choice would have been Paul Scofield, who was in his late seventies.

How each actor was chosen is the first of many epic stories surrounding the making of The Lord of the Rings. Ian Holm became Bilbo, in part because Jackson had heard him portray Frodo in the BBC radio adaptation; Christopher Lee was cast as Saruman as a result of reading for Gandalf; Elijah Wood, to prove his claim to play Frodo, produced a video of himself dressed as a hobbit in Hollywood Hills woodland locale. The model-turned-actress Liv Tyler was Arwen, for which her tall, long-limbed grace, flawless skin and dazzling blue eyes were a perfect match. She calls this the result of the decision of Jackson and the writer that “there wasn’t nearly enough female energy” in Tolkien’s books, indeed “the only female energy came from the big Black Spider that kills everybody . . .” So Arwen became the love interest, the only blockbuster sine qua non. Ian, never one to drop the idea, suggested impishly there might be some love interest for Gandalf (with, say, the dwarf Gimli).

This rejection of roles was duplicated with other characters. Daniel Day-Lewis was offered Aragorn but turned it down. Timothy Spall at one stage was due to be Gimli the dwarf; David Bowie wanted to play the elf Lord Elrond, but this never happened. Then Stuart Townsend was relieved of his part after two weeks of shooting as Aragorn—he was considered too young by Jackson—and replaced by Viggo Mortensen. But “they say” McKellen was “lured”—the word Brian Appleyard used—into The Lord of the Rings by the arrival at his home in Limehouse of Jackson with Fran, his wife, who had flown to London to meet and choose the cast.

Above all Gandalf is an enigma, insofar as we never quite get to the heart of his mystery, which is what Tolkien intended.“He’s not crazed,” Ian told Appleyard, “he’s just eccentric. He only has two shirts, he doesn’t wear shoes, he only wears shorts, he doesn’t shave, he doesn’t cut his hair. And he’s married to this beautiful Goth who did the screenplay. They’re New Zealanders—how else can you explain them?”

The preparatory work should never be underestimated: creating the films took eight years, with only one year to create the final version of each film.

Ian found Jackson adamant that he was not going to interfere with Tolkien and would eschew all fairy tale and pantomime. The image of Gandalf, inspired by the drawings of John Howe, was crystal clear in Jackson’s mind.

There is a tradition in Hollywood of distinguished British actors playing wise old mentors with supernatural powers. Olivier had been Zeus in Clash of the Titans, while earlier James Mason was the benign, omnipotent fixer in Heaven Can Wait. Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars was perhaps the closest parallel to McKellen taking on Gandalf, and of course Richard Harris would be Dumbledore in two Harry Potter films.

Jackson had no qualms when he settled on McKellen (and had the immediate endorsement of Ian’s Magneto in X-Men to inspire confidence), perceiving straight away that Ian was able to get under the skin of a character and cease to exist as Ian McKellen. Right from the start, with his prime intention of bringing the characters in the book to life, Jackson and Fran considered it of paramount importance that no one character should come to dominate completely over the others. So perhaps it was just as well Gandalf was not a stage role for Ian, or the balance might have been upset.

How should we describe Gandalf? “[He] is not, of course, a human being (Man or Hobbit),” Tolkien points out. “There are naturally no precise modern terms to say what he was. I [would] venture to say he was an incarnate ‘angel’—strictly an angelos, that is, with the other Istari, wizards, ‘those who know,’ an emissary from the Lords of the West, sent to Middle-earth, as the great crisis of Sauron loomed on the horizon.”

This was the intention the Jacksons had in their adaptation. They did not allow Gandalf to embody completely the author’s internally consistent, authoritative and controlling power. Instead they set out to allow Tolkien’s integrity and coherence, and sometimes his ambivalence, to come into focus slowly as guided by the storytelling demands, and the needs of the other characters.

This had been something a problem for Tolkien, too, for both in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings he sends Gandalf away from the main action and events, and in this way enhances the tension and immediacy of the drama, as well as the expectation and suspense of when he would return and intercede, either with success or failure. His attraction (and this underlines the parallel with, and closeness to, Ian himself) is his commanding distinctness. At the same time he is elusive in his core nature. Above all he is an enigma, insofar as we never quite get to the heart of his mystery, which is what Tolkien intended. There was a lot that made him a tempting role for Ian.

————————————————

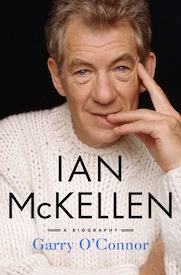

From Ian McKellen: A Biography by Garry O’Connor. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.