How I Met the Poet of Portsmouth

Or, Elegy to a Long Dead Cat Named Zane

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth: A Memoir of Place, Solitude, and Friendship chronicles Portsmouth, NH author Katherine Towler’s friendship with Robert Dunn, a brilliant poet who spent most of his life off the grid living in downtown Portsmouth. The book is also an elegy for a time and place—the New England seaport city of the early 1990s that has been since lost to development and gentrification—capturing the life Robert was able to make in a place rougher around the edges than it is today.

Barely a block long, Whidden Street comes to a dead end at the edge of South Mill Pond and has no real business being called a street. Houses pressed close together face each other across a strip of pavement not much wider than a hallway, their shuttered facades suggesting a scene from an antique postcard. In their mix of colors, cranberry red and white and mustard yellow, the older houses have the solid look of something that has been here a long time. Others are of a more recent vintage, rougher upstarts that match the broken pavement on their front stoops.

Our first night in our new house on Whidden Street, I stood at the window and gazed out at the rooftops bathed in the glow from the single streetlight. I had lived in other New England cities, but none of them had felt this old or this quirky, the very shape of the streets telling the story of the past. It was midnight, and I still hadn’t found the sheets in the maze of boxes that surrounded me. The sound of bells tolling the hour made me pause for a moment in my frenzy of unpacking. Though the steeple was blocks away in Market Square, it seemed I could reach out the window and touch those solemn notes. They brought the night close and made the darkness familiar in an unfamiliar place.

The dank smell of the pond came in through the window, mud laced with a hint of fish, and in the other direction from downtown I heard the piercing note of a boat’s whistle out on the river. The hourly tolling of the bells and the traffic on the river would become the soundtrack of my new life, noises that would soon fade into the background, but on that hot night in June of 1991, when I finally arrived somewhere I would stay longer than six months or a year, they struck me as the essence of this place I could not quite believe I was going to call home.

For more than a decade, since graduating from college, I had wandered up and down the Eastern seaboard in a restless search for a job, a relationship, and a life that made sense. All too often, I had packed everything I owned into a hatchback and started over, certain that another beginning would be the answer. This time I wasn’t making the move alone, and I was taking up residence in an actual house, not a one-room studio apartment. The man I was about to marry had driven a U-Haul truck loaded with both our possessions from Boston that morning and now searched through the mess of boxes with me, as exhausted and apprehensive as I was, both of us nervous and excited to discover where we had landed. In retrospect, our arrival in New Hampshire has a sense of inevitability, the moment when I finally stopped running, but that night as I sorted through our ill-packed possessions, I felt like I was standing in a doorway waiting to see whether I would step through to the other side.

We were woken at five-thirty the next morning by a very loud and raspy voice barking out the declaration, “Gonna be a hot one.” When I raised myself on one elbow and drew back the curtain, I saw a large, unshaven man standing beneath the window in the middle of the street. He wore paint-splattered work pants and construction boots. Beside him stood a petite woman in her sixties with a stack of newspapers in her arms. She handed him one and said, “If it burns off.”

“Oh, it’ll burn off all right,” he said.

The woman went back up the street, but he remained beneath our window with a coffee mug in one hand and the newspaper in the other, glancing from side to side as though expecting someone else to appear and continue the conversation. I would learn that Ed greeted the woman who delivered the newspaper like this every morning.

Fog hung over the pond in a milky sheen that gave the water the look of a clouded mirror. I made my way down the back stairs to the kitchen, thinking that even the weather here had an old-fashioned feel, the wispy fog seeming to trace the shape of tall ships coming into the harbor. The steps beneath my feet were worn down, hollowed into small depressions by nearly two centuries of use, and they were so narrow I had to descend carefully to avoid tumbling straight down the whole flight.

The existence of this staircase was one of the house’s idiosyncrasies. It was only a few feet from the front staircase, which rose from the hallway right inside the front door. Why two sets of stairs were necessary in such a small house was a mystery. This had never been a grand residence, even in the 1800s, the sort of place that might require a second staircase for the maid. I would become used to making the mental calculation—front stairs or back?—several times a day, a choice that seemed to link me to a host of people who had gone before me in this place.

I walked through the rooms strewn with random pieces of furniture, rolled-up rugs, and stray lamps, uncertain where to begin. It was then that I heard someone sneeze. Jim, I thought, still upstairs, but a moment later I heard him opening the refrigerator and realized the sneeze had come from a different direction. I crept to the window in the bathroom and peered around the edge of the frame. The profile of a woman was clearly visible behind a curtained window level with mine and only a yard away. She was setting a coffee mug on a table. It appeared that we were going to get to know our neighbors well.

The house needed a good cleaning before we could even begin to unpack, and after breakfast I unearthed the vacuum and set to work. The place had clearly seen hard use by previous tenants; the walls were pockmarked with nail holes, and the paint was worn. Still, it felt like a palace to me, with three rooms downstairs and three upstairs. I wasn’t used to having this much space, and I found the sloped floors and narrow closets with their tiny, latched doors fascinating. Evidence of just how old this house was—1830, the rental agent had told us—was there wherever I turned: the thin lintels of the mantelpieces, the ceramic doorknobs with their amber hue, the antique glass in the windows that gave the scene on the other side a wavering quality, like a drawing done in sand. I was enthralled with this shabby old place, with the idea of living in a house so quintessentially New England.

When I set off later that morning to find a supermarket, I stepped out the front door directly onto the street. There was no room for a sidewalk. Cars did not belong here, though the residents owned them, of course, in some cases two or three vehicles to a house. Where to put all these cars, we would discover, was a constant source of conflict. I had to inch out of the single spot beside our house to avoid hitting the house across the street.

When I returned from the supermarket, a towheaded boy came running from a house a few down from ours, extended his hand, and said, “Welcome to Whidden Street.” He went on to recite a litany of facts about dinosaurs at a rapid speed that made it impossible to follow half of what he said. At the end of this breathless outburst, he said, “I’m Nate. I’m six. Do you have a cat?”

Yes, I told him, we did have a cat.

“I thought I saw a new cat.”

“Was he gray?” I asked.

“Yup, gray.”

“That’s Zane.”

Nate nodded and zipped off as quickly as he had come.

We met most of our neighbors over the next few days. It was hard to avoid, living in such close quarters. Eleanor came over to introduce herself from the house directly across the street, where she lived with her mother and her niece. Her parents had owned the place since the 1940s, she told us, and she had grown up there. Eleanor belonged to the group of old-timers on the block whose houses, like ours, remained pretty close to their original states. Nate’s family was in the other camp, recent transplants who had restored their antique houses to a polished authenticity. Being renters, we fell some- where in between the two groups. No matter how long any of us had been there or where we had come from, though, we were united by the cats. Whidden Street really belonged to them.

We had just Zane, a fiercely smart and independent stray Jim had taken in down in Boston, where he had been living when we met, but our neighbors had two or three each, which meant that the felines outnumbered the humans on the block. The lone plot of grass adjoined our house, and it was here that the cats congregated and engaged in a contest to determine who would rule this corner of town. The contest had been decided before we arrived on the scene—Roscoe, a mean orange tabby, would tear up any cat who challenged him—but Roscoe felt compelled to remind the other cats of this fact on a regular basis.

Those first weeks in Portsmouth, I went out walking, exploring the town by wandering its maze of skinny streets. Most days I encountered a tiny, gaunt man somewhere on my route—crossing Market Square, emerging from the post office, or seated on the stone wall by the eighteenth-century gravestones on Pleasant Street. He moved with a slow deliberation, shoulders hunched forward, in a flimsy black trench coat and a flat cap, a styrofoam coffee cup in one hand and a cigarette between the fingers of the other. His face was framed by glasses with thick, black rims, and a bristled mustache obscured his lips. He might have been in his late forties or early seven- ties; there was no way to tell. He seemed to be a fixture downtown, a part of the streetscape, and I assumed from this and his worn clothes that he was homeless. He had the look of someone who wandered with no destination and might not have eaten in some time.

This strange, little man moving like a leaf nudged by the wind, his body bent in such a stoop that he appeared not much more than five feet in height, though he was clearly taller, belonged among these streets that had once been cow paths. He struck me as a figure, like so much in the landscape of Portsmouth, out of another century. One afternoon when I happened to glance out the window at the right moment, I saw him passing by our house. What was he doing, I wondered, all the way at the dead end of Whidden Street? The next day I paid closer attention and caught him emerging from the house on the other side of our patch of lawn, by the pond. Shortly after this, I stepped onto the street one day just as he did so. He raised his head, and his eyes darted away, the only acknowledgment I received.

Our house, like many in the neighborhood, had a dirt cellar. When I took the shallow stairs into its dank depths, I could see the rock ledge on which the foundation rested, jutting from the dirt wall behind the furnace. Almost two centuries earlier, the earth had been carved to hold the house, and it was easy to imagine men with shovels executing the job. A window not much bigger than a business envelope was cut into the base of the foundation. We left the window unlatched so Zane could go in and out. When the garbage men backed their truck down Whidden Street, he would fly through the window and race upstairs to hide under the couch.

One evening we found Zane crouched by the basement door hissing. Further investigation revealed Roscoe pressed to a moldy corner of the basement. We propped the window open, but he did not budge. After fifteen minutes of attempting to coax him toward the window, we went out into the yard to call him from the other side.

Jim and I were standing next to the house, calling Roscoe’s name, when the diminutive man I had observed downtown came down the street. It was a cool night, and he was wearing a brown corduroy jacket that looked like a relic from the 1960s instead of his trench coat. He stopped when he reached us and said, “We have a renegade cat, do we?”

I had not articulated it to myself, but clearly I had formed an expectation of what it might be like to hear him talk, because I was so startled by his speech. I explained that Roscoe was in the basement, refusing to come out.

He bent down by the basement window and called, “Roscovitch, my dear Roscovitch, do come here.”

He sounded like he was reciting Shakespeare in his soft and lilting voice. After a moment, Roscoe jumped through the window and went darting toward the house next door.

“I do apologize,” he said. “But I’m afraid that cat has a mind of his own.”

I thanked him, but he had already turned away and evaporated down the bit of pavement between our houses.

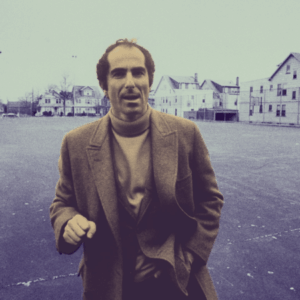

Katherine Towler

Katherine Towler is author of the memoir The Penny Poet of Portsmouth and the novels Snow Island, Evening Ferry, and Island Light. She is also co-editor with Ilya Kaminsky of the collection A God in the House: Poets Talk About Faith. She has been awarded fellowships by the New Hampshire State Council on the Arts and Phillips Exeter Academy, where she served as the George Bennett writer-in-residence. She teaches in the MFA Program in Writing at Southern New Hampshire University.