How I Learned To Write Dialogue By Reviewing Police Complaints

K Chess on the Heightened Listening of Transcription

“Did you see the badge number or nameplate of the officer who hit you?” I heard myself say as I played back the interview tape.

“No.” As the tinny reply sounded in my headphones, I could picture the speaker, a white guy in his early thirties, chubby and tentative. After his arrest outside his apartment building, his mother had filed a complaint on his behalf with the Civilian Complaint Review Board. She said a female cop had struck him with a baton while kneeling on his back. I was the investigator assigned to the case, charged with determining if unnecessary force had been used. In a bare room at 40 Rector Street, the agency’s Lower Manhattan headquarters, I’d taken sworn statements from both mother and son. Now I was transcribing the tapes for the case file.

“What did the officer look like?” I asked him. Silence. Then my voice again. “Can you describe her?”

“I don’t really know.”

The transcript I was typing up now would join the documentation generated by this man’s arresting officers, their memo book entries and stationhouse logs and duty rosters. CCRB case files could be stuffed with all kinds of other things, too: court complaint forms, stills from security camera footage, rap sheets, subpoenaed hospital records, Polaroids of gruesome injuries. But this particular guy hadn’t been hurt. He didn’t even seem angry about his arrest. Maybe he was going along with the process to make his mother happy. “Was the officer white?” I asked him. “Black? Hispanic? Asian?” These, along with “Other,” were the five NYPD categories for race in 2008.

“I don’t really know,” he said, voice monotone.

“OK. Do you remember her hair color, though? Eyes? Anything like that?”

“No.”

“What about her build? Was she tall? Short? Heavy? Thin?” In the recording, my voice was beginning to sound frustrated. “Do you remember anything else about the way the officer looked? Anything at all that might help us identify her?”

“Well, sure,” said the complainant, after a long pause of consideration. “There was one thing. She had a little bit of booty on her.”

*

The CCRB was my first job, other than work-study and making sandwiches at Subway. I had a heavy gold badge stamped with the word INVESTIGATOR, issued to me in a black leather flip wallet worn in by unknown predecessors. I had business cards and an official stamp that showed me to be a Commissioner of Deeds. I had a wardrobe of dowdy professional clothing bought at the Daffy’s in the basement of the Atlantic Terminal mall with money my grandmother sent from Michigan. I was 22 years old.

*

There are millions of different ways to live in New York, and working at the CCRB introduced me to an excellent cross-section. Incidents that turned into complaints could happen anywhere—on a front stoop in Sunset Park or at an exclusive sneaker release party in Soho, at an unlicensed daycare center on Fordham Road or at the Staten Island Ferry terminal. For each case, investigators might conduct more than a dozen interviews with New Yorkers alleging misconduct, police officers and witnesses. Our tagboard folders bulged with Maxell-brand cassette tapes. Investigators kept red-and-black boxes of plastic-wrapped spares on our desks.

I talked to cops who did all kinds of jobs—transit cops and housing cops, vice squad and gang squad, patrol officers, desk sergeants and lieutenants.

I took statements and I listened; an interview calls for a specific poised attention that’s very different from what a conversation requires. As I reviewed and transcribed and analyzed the statements, my focus could not stray. All this listening to how people speak. It taught me to write dialogue.

*

Among people who write about writing, it’s commonly recognized that dialogue does not resemble actual human speech. James Wood says that the way we talk “tends to be dribblingly repetitive, and relatively nonfigurative, nonpictorial.” When writers put words in our characters’ mouths, then, what we are creating is wholly unrealistic, both more poetical and more direct than any transcript could ever be.

I’ve listened to hours of tapes, and I agree with this up to a point. People “um” and “uh” a lot. We repeat ourselves. Listening closely to our speech—cop and civilian, interviewer and interviewee alike—is an exercise in frustration. We talk over each other heedlessly. We refuse to answer what we’re asked. We fail to follow up on the questions that turn out to be the most important.

I’m a connoisseur of these foibles and what they tell a careful listener. The words we choose provide clues to how we were raised, how we spend our time, who we aspire to be. We are unguarded—or the ways we guard ourselves are telling. We contradict ourselves. We lie.

*

“I do not recall.” That was the standard cop interview answer, one I transcribed over and over. From a legal standpoint, claiming not to remember is safer than straightforward denial. But it wasn’t the only answer I got. Some officers went through incidents with me step by step, too eager to justify their decisions to heed the stifling glares of the union reps who were always present in the interview cubicle.

If I’d had in my mind a certain kind of cop from TV, a heavyset middle-aged no-BS Italian-American guy with a Brooklyn accent, well, I met plenty of those. But the stereotype does not capture the full variety of the city’s police force. At the time, NYPD personnel numbered 34,000, bigger than many countries’ militaries. I talked to cops who did all kinds of jobs—transit cops and housing cops, vice squad and gang squad, patrol officers, desk sergeants and lieutenants—and like other New Yorkers, they came from all over. What surprised me about their speech was the stiltedness of response, the way they borrowed words straight from the patrol guide. “At this point, I administered OC spray,” a rookie PO might say, her formal diction hard to distinguish from the veteran Emergency Services tactical team member who’d told me, “I advised him to stop flaring his arms” just the day before. “Cop-speak,” we investigators called it.

Speech is highly contextual. For instance, the way officers talk to investigators, on the record, when they are potentially up for disciplinary action, is totally different from the way they’re accused of talking during the incident itself. “Give me your fucking keys.” Or “Say something again, and I’ll lock you up.”

With so many cops in New York, anyone might have a run-in with the police. This was an era before decent cell phone cameras became ubiquitous, so many of the stories of mistreatment that I heard seemed plausible but couldn’t be proved. That bummed me out. But the unpredictability of individual expression often gave me joy. “Do you smoke after sex?” a young ultra-Orthodox Jewish man claimed to have asked the officer who’d just pulled over his minivan for a busted tail-light and failure to signal. He’d surprised even himself with the non sequitur, which infuriated the cop. “I don’t know why I really said it,” the complainant told me. “I guess I just wanted to give him something, something for those tickets he wrote me.”

You can’t make this stuff up.

Or can you? Richard Price, often praised for the verisimilitude and unforced whimsy of his dialogue, recounts his own research process to the Washington Post as follows: “I just want to know the parameters of plausibility, and then I want to lie responsibly.” Riding along with cops or hanging out with drug dealers, Price would write down snippets of observed speech in notebooks, but he says he never really bothered to read through them afterward. The process could be likened to that of a plant drinking in light and producing chlorophyll; the writer makes dialogue, brand new, from the everyday rhythms of overheard conversation. Zadie Smith admits she has a gift for this, for the “trick of breathing what looks like life into a collection of written sentences,” creating voices “that come from nowhere and live on in our consciousness, independent of real people.”

Smith and Price have rich imaginations, but imagination draws upon knowledge. Attending to the details of the words people choose is a way to begin to know other things about their lives. When I worked for the CCRB, I learned for the first time what men’s haircuts are called: a “fade,” a “low caesar,” a “baldie.” I learned that there is no unanimity among New Yorkers about where to put the emphasis in the word “umbrella”—some choose the first syllable and others the second. I learned that many Caribbean immigrants use the old-fashioned term “paddy wagon” for a prisoner transport van and that to “brace” someone against a car means to hold your forearm across their body to pin them in place.

“Hell, they swiped my cheeks like a MetroCard!”

Toni Morrison, another terrific writer of dialogue, embraces the specificity of the Black speech she heard growing up. She describes herself as “determined to take the language that for me was so powerfully metaphoric, economical, lunatic, and intelligent at the same time—just these short sentences or these developments of ideas that was the language of my family and neighbors and so on—and not make it exotic or comic or slumming.” Morrison does not doubt her community’s way with words; she approaches dialogue with respect and admiration.

In order to depict how people carry on their lives in a place as large and complicated as New York, a writer must listen to the city’s heterogeneous languages. It’s not possible to master them all. But listening well is the first step.

When we recall real speech from a distance of time, our memories edit out the repetition. We remember idiosyncrasy, expressiveness and beauty. Ten years after quitting the CCRB, the language I have not forgotten is lucid and colorful and perfectly apt. A complainant, asked to describe an unlawful strip-search in a holding cell, said, “Hell, they swiped my cheeks like a MetroCard!” Another complainant remembered calming his brother, who was thrashing on the ground to avoid handcuffs, by telling him, “be humble.” The eloquence of this restraint still give me chills.

Listen. Listen for the personality. The individuality. Find pleasure in this duty.

![]()

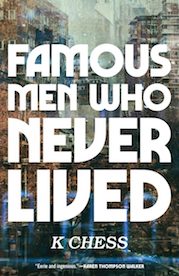

K Chess’s new novel, Famous Men Who Never Lived, is available now from Tin House.

K Chess

K Chess is the author of short stories honored by the Nelson Algren Literary Award and the Pushcart Prize. She was a W. K. Rose Fellow, earned an MFA from Southern Illinois University, and currently teaches at GrubStreet. She lives with her wife in Providence, Rhode Island.