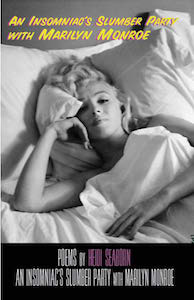

How I Kicked Insomnia and Addiction with Help from Marilyn Monroe

Heidi Seaborn on Sleeplessness, Ambien Dependency, and the Blessing of Unexpected Muses

2:37 in the morning. It’s my tenth day in Paris; my jetlag has subsided, but insomnia has kicked in. I unscrew the Frida Kahlo pillbox I purchased in October 2018 at the gift shop of Frida’s blue home in Mexico City, lick my finger, and pick up a half tab of Ambien. I do this in the dark. Sip of water. The taste of tin on my tongue, I settle into my pillow and begin a word game to trick my mind into not thinking. I pick a category. Tonight, it’s cities I have visited. I name them in alphabetical order. Atlanta, Berlin, Chicago, Denver, Edenborough, Frankfurt, Greensboro.

It’s not working. I give up and sit up in bed. I’m in the final year of the NYU Low-Residency MFA in Poetry, which brings me to Paris twice a year. Yes, my life as a poetry student in Paris is as glamorous as it sounds—but in the dim light of January dawn, I see my thesis draft looming on the table in my hotel room. It’s a giant pile of poems written in the persona of Marilyn Monroe. And it, or she, is calling out to me.

At this point, I’ve spent 18 months writing as her—that lilting flirt of a voice flowering in my head as I researched her life and deepened my poetry knowledge and craft. It’s not like I had a thing for Marilyn Monroe. She was just a beautiful, tragic, Hollywood star who happened to be the perfect trope for exploring what I really was interested in—our celebrity obsession and performance culture.

Here was the woman that transformed herself from Norma Jeane Baker into Marilyn Monroe and then performed as that character whenever she stepped out the door. A woman that pioneered multiplicity, the concept of blanketing the world with her image, before the Internet made it easy. She understood how celebrity gave her power in the male-dominated Hollywood. She was the perfect persona for me to inhabit. It didn’t hurt that she had dabbled in poetry as well. I chose to write as Marilyn. But in the end, I think she chose me.

Beginning when I was a pre-teen, I would lie in my twin bed at night listening to late night talk radio to fall asleep. Somehow, I could receive the San Francisco KGO 810 broadcast of Ira Blue all the way where I lived in Seattle. His show music was, not surprisingly, Ira Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. That music, and Ira Blue’s gentle rapport with callers, would nudge everything else out of my mind, like a gentle sweep of the kitchen after dinner, and I would drift off. Then Ira Blue died and I stopped sleeping.

I was 16 then and insomnia felt like just another rung on the ladder of growing up. Like getting a summer job or kissing. The adults I knew were too busy to sleep much. I’d hear my father downstairs in the kitchen at night. The cookie jar lid settling back on its lips, his shuffle up the stairs, past my room. I began to think of sleeping as the provenance of children or my younger siblings. I started to hold those hours of lying awake as sacred, a sign that I had crossed over a threshold to the consequential and I began to worry like an adult.

The day Marilyn turned 16 she was married off to Jim Dougherty, the 25-year-old son of a good friend of her then-guardian, Grace McKee. Grace and her new husband and family were moving to Chicago. There wasn’t room in their life anymore for Marilyn, so she was given the choice of returning to the orphanage or marrying Jim. I imagined Marilyn awake at night, her childhood anxieties becoming adult worries. But they were truly grown-up concerns: she was a teenager who was suddenly a wife, with no father and an institutionalized mother, and the world was going to war.

Someone recently asked me what it was like to be my 16-year-old self and if I would like to reclaim that girl. For me, my 16-year-old self was navigating her future, maneuvering around challenges, and sensing who she could become. The open hours of night became the space where I could imagine my future. And so, I came to embrace insomnia as my secret weapon—the extra hours I had to problem-solve or formulate a plan or study or work. My logic translated into the belief that longer days meant I could accomplish more. And eventually, it tricked me into thinking that insomnia was its own accomplishment.

Marilyn and I took different paths into the world of sleeplessness, but once there, we both experienced insomnia’s highs and lows. Initially, to be wakeful when the world sleeps provides a place of quiet to establish oneself, to revisit experiences, to prepare, or just to escape through a book or a film. I used my longer waking hours to be more productive. I could hold down a job, excel in school, play sports, volunteer, take extra classes, have a boyfriend, have friends, do everything. I blasted through university in just over three years, I started a business when I was 24, sold it by 26. This insomnia stuff was magic in my mind. But I was also married three times by the age of 30.

Marilyn and I had that in common too. Not only three marriages by 30, but achieving success in some parts of life and failing in others—the ones that required mindfulness and self-knowledge. The adage, “sleep on it” comes to mind. But if one rarely sleeps, that moment of deep contemplation can be elusive. There is an edge that sets in from chronic lack of sleep.

And eventually, it tricked me into thinking that insomnia was its own accomplishment.

I’m sure everyone has experienced that feeling of being on edge, a little off after a poor night of sleep. Maybe your thinking is slower, or your nerves excitable. Your emotions easily surface or perhaps dull. You are not at your best. For those of us that are life-long insomniacs, we may have tricked ourselves into believing that we “function” on very little sleep. I know I did for over 30 years. Marilyn had no such magical thinking. She knew she needed sleep and yet it didn’t come. Hers was a lifelong chase for a full night of natural sleep.

Marilyn’s inability to sleep brought on by anxiety prompted her film studio, Twentieth Century Fox, to send her to the studio doctor, who in turn prescribed barbiturates to help Marilyn sleep. The barbiturates worked to knock her out for a while. But she quickly became addicted and started increasing her dosage.

In the end, she was shopping doctors as well as cracking open a Nembutal capsule (so that it would absorb faster into her bloodstream), then adding a chloral hydrate tablet to create a super sedative known as a “Mickey.” She then would mix this with champagne or a stronger alcohol. The result is that when Marilyn finally got to sleep, she slept the sleep of the deeply sedated. She became famous for being late for everything. She also experienced several close-call overdoses over the years. While her death was ruled a suicide, it occurred from a toxic overdose that may well have been accidental.

To write in Marilyn’s persona, I had done my research. I learned and wrote about her issues with sleep and addiction and so much more. I ended up writing nearly 100 Marilyn poems. And revising many of those over and over. Each poem, each revision bringing me close to Marilyn. I decided to write about her death as a long sonnet sequence.

Imagining the unraveling of her mind as she lay on her bed in her Brentwood home, calling her psychiatrist, Dr. Greene, to come which he did, and then after he left calling other people in her life. I eventually unraveled the form of the poem to match her state of mind as the drugs kicked in and she became less coherent. I had climbed inside the head of a woman desperate for sleep, finding it more and more elusive as her addiction to sleep medication morphed beyond her control.

Here I was writing about someone struggling with insomnia as a chronic insomniac, but not making the connection to my own struggle. It didn’t occur to me during the 18 months that I had been researching and writing the poetic version of Marilyn. Not that night in Paris in January. I didn’t have a problem with sleep, I thought. Not really, not for years. After spending most of my adult life functioning, even excelling, in my view, on five or so hours of sleep, I finally started sleeping a few years ago.

It happened once I left a difficult marriage and moved back to my childhood town. Maybe being back home reminded me of being a little kid who could sleep forever or breaking from a toxic relationship did the trick. Anyway, I started sleeping six hours, then seven. Even eight on occasion. It was an elixir. I wrote about it at the urging of the now sleep-doyenne Arianna Huffington. I became another star example of her mission to get people to sleep.

I thought I was done with insomnia. I bragged about sleep the way I used to brag about not sleeping. But whenever I packed for a trip, I packed Ambien. And I would take a half pill or a full pill every night of my trip. Remarried to an easy sleeper, I started to find myself awake now at home from time to time. I’d lie there for a while. I invented the alphabet game and it worked. But some nights nothing stopped the adrenaline from running through my body and revving up my mind.

When that happened, I’d get out of bed, slip into the bathroom, quietly open my drawer and pull out my travel pillbox and take Ambien. It worked. I’d find that deep, narcotic Ambien sleep. In the morning, my husband would quiz me—“you were sleeping really deeply, did you take an Ambien?” Not concerned, just curious. But in the daylight, his question served as a reminder. I would vow to just push through it next time. But the “next times” were adding up. Then I found myself in Paris, and after that back home and the sleeplessness continued.

I had climbed inside the head of a woman desperate for sleep.

Then one day, when I went to pick up a refill of my Ambien prescription at Rite-Aid, the bottle held only 12 pills for three months. “Insurance restrictions,” said the pharmacist. I could feel myself panicking. I had some trips coming up; what would I do?

Meanwhile, I kept writing my Marilyn poems. At a series of poetry readings, I decided to read some of my new work. At one reading, I launched into a poem about Marilyn’s addiction to barbiturates and her denial or magical thinking about it. The lone stage light illuminated me standing at a podium holding a sheaf of poems. I found myself pausing for an uncomfortable time at the end of the poem and then, before going on to read the next poem, I confessed my own addiction to Ambien. I think I rambled on about it a bit amongst these strangers who had come for poetry, not AA. I shuffled my poems, read another one quickly, then left the spotlight, walked to the back of the auditorium, and out the door. The night was cool, noisy.

All this time, and I hadn’t seen the parallels. I hadn’t seen that I had fallen down the same rabbit hole, even as my thesis advisor had been pushing me to find common ground with Marilyn and write toward that. Now I began writing about my own insomnia, my own addiction. I found the work flowed easily, poem after poem. I could feel Marilyn on my shoulder. Now she was both muse and empathetic example. I had thought I was channeling through her; she was actually channeling through me—her precedent became my presence and eventually a present, the gift of rewriting my own outcome. As I wrote and revised, I discovered that I was sleeping longer, deeper, just better. Without Ambien.

It is now a year since I confronted my addiction. I’m off the Ambien and I’m sleeping better. That doesn’t mean I sleep well every night. I imagine few people do. When I’m lying awake midnight, I still play word games to trick my mind out of a spiral of worries. Sometimes, I get out of bed, sit down at my computer and start writing. Even though I’ve finished the Marilyn book and have shifted my energies to other creative inspirations, I sense her there with me, in the middle of the night, keeping me alive.

__________________________________

An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe is available from Pank Books. Copyright © 2021 by Heidi Seaborn.