How I Created Community With a Ramones Fan Club

Kid Congo Powers on the Smartest, Dumbest Rock ’n’ Roll Band There Ever Was

The Ramones were the smartest, dumbest rock ’n’ roll band there ever was. The New York influence that came through the Ramones was quite different from anything I’d heard before: a new attitude and feeling, almost avant-garde in its simplicity, with rocket-fueled emotions wrapped up in lyrics so stupid they were insightful. Whatever it was, it was RIGHT for me.

I loved them with a passion unmatched and all the fanaticism they deserved. I was so enamored with the group that, toward the end of 1976, I started their West Coast fan club. I wanted them to be huge, like something out of Tiger Beat magazine.

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, throwing myself into this new venture provided me with something to focus on and pour my energies into after Theresa’s death. It was my way of reaching out and connecting with others, especially this burgeoning community of freaks I was now a part of in the nascent punk rock scene. This was during that all-too-brief moment before punk became too cool or trendy. We were a group of really strange, disparate misfits, looking for something new.

I had a mailing list of twenty-four Ramones friends and fans I’d met at the band’s first LA shows. With me as de facto “president,” that made twenty-five of us. That seemed like a pretty good start. I sent a letter out to everybody announcing the formation of the club.

We were a group of really strange, disparate misfits, looking for something new.

“Hello and welcome to the Unofficial Ramones Fan Club,” I wrote. “I know that some of you guys have been waiting for a long time and we thank you for being so patient.” The band’s debut album had only been released in April, but eight months in teenage years felt like an eon. “The reason for this club being called ‘unofficial,’” I continued, “is because we can’t collect money without going through a lot of hassle. The main one being we’d have to pay taxes.” Smart.

Among the core fan-club crew was a girl gang from Palos Verdes: Mary, Helen, Trixie, and Trudie, aka “the Plungers.” Mary became known as Mary Rat. Helen chose one of the best punk names of all time: Hellin Killer. Trixie Treat was a tigress punk with black spiky hair, black absolutely everything, who seemed to always be in perpetual motion, moving, whirling, dancing, with rosaries flying around her neck. And Trudie Arguelles was, well, Trudie. She was truly exotic and dangerous-looking, with a dark shag and smoky black eyes. Her makeup was inspired by James Williamson, and her hair by Jeff Beck. She took her style from the male rock stars we all loved and made it her own.

There were also kids in our group who were even younger than me: sixteen-year-old Paula Pierce and her fifteen-year-old friend Robin Cullen were the bass player and drummer, respectively, of a precocious glam pop-punk band called the Rage, heavily influenced by both the Ramones and the Quick, at whose concerts I first encountered them. Paula later fronted all-girl garage band the Pandoras.

Jenny Stern from Mission Hills, known as Jenny Lens by all and sundry on account of the camera forever slung around her neck, was a few years older than us and already an accomplished artist, with two degrees from CSUN and CalArts, when I first met her at a Ramones show. Just as I had been inspired by the Ramones to start a fan club, Jenny picked up a camera and dedicated herself to documenting the LA music scene, bringing a unique vision drawn from her fine arts training. Patti Smith used to call her “the girl with the camera eye.”

I had been a member of the official Sparks fan club. With that you got a newsletter and a photo with a badge. Although it was a one-man, DIY affair, I wanted my Ramones club to be as professional as possible. As I was already writing reviews for my high school newspaper, I decided to write, edit, and lay out the newsletter myself, taking a cue from Back Door Man and early punk fanzines I’d heard about in England like Sniffin’ Glue, which were just photocopied sheets of paper stapled together. Jenny agreed to let me print the amazing photographs she’d taken of the group when they first came to LA, the year before, and use her test strips. It was so very punk to use the scraps!

[It] made me feel important and accepted, to be seen by the band as part of the movement helping to promote their music.

The oldest member of the club was a schoolteacher, Herb Hammer. We met at a show too. He had curly hair and round glasses and looked like a professorial hippie. He was an adult among a sea of kids, just very young at heart. He didn’t see any difference between his enthusiasm and our enthusiasm—and we didn’t see any difference either. So he lent a helping hand to organize the fan club and, as I didn’t have an ID, he applied for the PO box in his name so I could receive fan club correspondence. My Bassett High School friend Pester also made every Ramones show without fail and was a great cheerleader and supporter of my activities.

I grew the fan club by word of mouth, meeting others at shows, taking their addresses or having them send me a self-addressed stamped envelope. The band’s record company, Sire, saw my grassroots efforts as a good thing for the band. Sue Sawyer, who oversaw the Ramones’ publicity in LA, let me come to her office to print out my newsletters and used to give me all the latest dish on what was coming up in Ramones world. I also had access to all the Ramones promotional swag—like the special switchblade comb, posters, and publicity photos. Right before the Ramones’ second album, Leave Home, was about to come out, Sue invited me to hear a test pressing in her office with Phast Phreddie of Back Door Man fanzine and Don Snowden, who wrote for the LA Times.

Plans were already underway for the first newsletter when the Ramones arrived in LA again for a week of shows at the Whisky with Blondie. The newly formed Ramones “unofficial” West Coast fan club decided to personally welcome our heroes to town. We even found out what flight they were coming in on and met them at the airport.

That week felt so significant, I memorialized the most noteworthy events on a scrap of paper for posterity:

1. Greeted Ramones at airport—Tues, Feb 15th. Brian, Marcy, Debbie, Robin, Helen, Mary, Herb, Roxy and Jenny.

2. Wednesday, Feb 16th—Called Sunset Marquis and talked to Danny Fields. Went and met him at the hotel. Saw Dee Dee by pool. Left and saw Dee Dee by elevator. Saw Johnny & Roxy in street and Tommy too.

3. Went to sound check at Whiskey and watched them tape “Metro News, Metro News.” Robyn & Debbie talked to Dee Dee & Joey after over. I observed and acted cool (my favorite pastime).

4. Went to the show. Was a lot of fun. Sue Sawyer took me.

Jenny Lens and I actually went to the Sunset Marquis together. She had arranged to show the band’s manager, Danny Fields, the photos she’d taken of them. I tagged along to tell him about my fanzine. By now, my identification with the group was complete. I had grown and cut my hair into a near-perfect replica of the Ramones bowl-cut shag that kissed my shoulders and dropped below my eyes. I looked like a mini-Ramone clone. Danny took a photo of me sitting cross-legged by the pool, examining the contact sheets of the photos Jenny brought with her. In front of me, Dee Dee flexed and posed like a scrawny Charles Atlas in his mini-briefs. I cornered Joey and got him to write a little note to the fan club. He hailed me as “the Prez.” From then on, anytime my friends and I showed up at a Ramones show, he would announce, “The Prez is here!” It was a real thrill, and made me feel important and accepted, to be seen by the band as part of the movement helping to promote their music.

At the same time, I understood I was still a fan, not a friend, and had no intention of stepping over that boundary.

Even better, they wanted to hang out with us, find all the good record stores, and go junk shopping. Everyone was driving them around; different people had different Ramones. My high school friend Pester had a car. Johnny wanted to go to comic book stores, so we took him and his girlfriend at the time, Roxy, who had a tough Chrissie Hynde kind of look with mascara and bangs. Roxy was a little scary but super-cool. All the girlfriends were as friendly to the fans as the band. We took Joey around a bit also, but Joey was in great demand; he was a fan favorite and the most approachable.

That week, it really felt like we were connecting with the group on a personal level. This was something totally new in rock, though. There had always been a strict demarcation between fan and band. With the advent of the punk scene, fans could not only talk and interact with their idols but be involved with promoting their music. At the same time, I understood I was still a fan, not a friend, and had no intention of stepping over that boundary. I didn’t want to infringe on their privacy. I wanted to be respectful, not come in and take a seat at their table.

The highlight of Ramones week was a party held in their (and Blondie’s) honor at a Craftsman house on Wilton Avenue in Hollywood, known as the Wilton Hilton, that was home to Tomata du Plenty and Tommy Gear, the front man and bandleader, respectively, of a group who were recent transplants from New York, the Screamers. I was in awe at the idea of being at a house party with the Ramones and Blondie. That night, the house was packed to bursting, and I met two girls there who would become my closest friends and allies: Pleasant Gehman and Theresa Kereakes.

_____________________________________

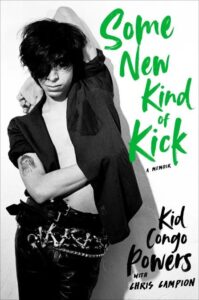

Excerpted from Some New Kind of Kick: A Memoir by Kid Congo Powers with Chris Campion. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Kid Congo Powers

Kid Congo Powers is a guitarist and singer-songwriter best known for his work with The Gun Club, the Cramps, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. He is currently the frontman for Kid Congo & The Pink Monkey Birds. He lives in Tucson, AZ.