How I Came to Know My Cuban Grandfather Through Archival Research

Elena Sheppard: "I saw quickly and clearly that in many ways our minds were stuck in the same loops."

My grandfather died when I was 10. He was 85 years old, which to little-kid-me meant that he was ancient. I remember him creaking barefoot around the kitchen with a box of diabetic cookies in his hand. I remember him sitting in a straight-backed folding chair when we’d go to the beach. I remember his big hands, and long ear lobes, and the way his toes stacked on top of one another like tectonic plates running out of room.

My grandmother, on the other hand, lived for another 25 years after her husband died—which meant my relationship with her extended well into my 30s. We were close, intertwined, talking on the phone about my life and hers, spending weeks together over the holidays. What I loved talking to her about most, though, was her past. Sometime in my teen years I became obsessed with the life she lived before I was born, before my mother was born, back when she was a little girl growing up in a small town in Cuba.

She’d tell me about her girlhood, her mother, her grandmother, and then we’d zoom forward in time and she’d tell me about becoming a mother to her own daughters; she’d tell me about the start of the Cuban Revolution and her husband’s choice between exile in the United States or prison. She’d tell me about their early days in Florida, the whole family trying to learn English, and scraping by on my grandfather’s tomato picking money, and the community of Cuban exiles who helped one another make this new country feel something like a home. I was a rapt audience every time; my questions had no end.

I recognized in his writing a familiar feeling of responsibility for family stories and small-town landmarks and everyday people on the verge of being lost to time.

In the years before she died, my grandmother’s mind began to go, until it was nearly entirely gone. She’d forget me, she’d forget herself. Somewhere in the expanding voids of her memory, I realized that I wanted to write her life down, not just wanted to but needed to. I felt a responsibility to preserve the stories she’d told me; the stories of women and their daughters in Cuba, and then a woman and her daughters in the United States, suffering the tragedy and joy and hardship and just plain existence of the Cuban diaspora. Four years before my grandmother died, already sick with dementia, I began to write a book.

Some of the stories she’d told me about her life, and about her ancestors’ lives, I’d had the forethought to record. When I began my project, I dug back through those files, and found her voice; I never stopped feeling grateful for the hours I had of her telling her life in her own words. But after listening and transcribing and listening again, I felt different holes in our family’s history. I began searching for more stories.

So much gets abandoned when a homeland is left. The place itself, of course, but also artefacts—photographs, diaries, heirlooms. I have a shoebox of photographs of my family’s life in Cuba—they are a random assortment of memories that begin in the late 19th century and then stretch forward in time until they suddenly stop in 1960. They are pieces of our family history that have been painstakingly collected through the decades as people have gone back to the island, and searched through what was left behind, bringing anything they find with a hint of our family back to the U.S. with them when they return. My grandparents’ wedding photos never made it off the island, but there are pictures of my grandparents when they were young and at the beach. There are no birth announcements for my mother or her sister, but there are pictures of them in cowboy costumes at a photo studio sometime in the mid 1950s.

Stored with the photos, as long as I can remember anyway, was a large envelope. The envelope, I was told, was filled with my grandfather’s writing. If I really rustle the leaves of my memory, I can see him in the kitchen in my grandparents’ Miami duplex typing on a typewriter. I never knew what he was writing, and I was far too young to wonder, but my mother later told me it was stories of Cuba: Things he was worried the Revolution would erase, she said. Stories he knew people would forget if he didn’t write them down.

My impression of his writing, before I read it, was that it would be filled with all the seriousness of Cuba’s 19th century struggle for independence. I knew my grandfather had been a history buff, and I knew he’d been a patriot, and I imagined his writing would sternly hit those marks. When I had exhausted my grandmother’s stories though, I decided to see what his held. I opened the package of papers, the remembered smell of my grandparents’ Miami duplex hit me like a wave, and I understood instantly that I was opening a portal to his life. My grandfather wrote on thin carbon paper and his stack of words was nearly translucent, but they were there and waiting for me. I sat down and I read.

Some of his writing was indeed about the Cuban War of Independence, the generals and battles that left an impact on the war and on his mind. But some of the writing was more personal; when he wrote about his family, I felt a prickle of recognition. There was an undeniable similarity between his accounts of his family’s history, our family’s history, and my own. We never had the chance to speak of it, but I saw quickly and clearly that in many ways our minds were stuck in the same loops; our writing, a desperate attempt to freeze frame a shared ancestral home.

Just as I wrote my grandmother’s stories, he wrote his grandfather’s. Just as I tried to capture the history of Cifuentes in the 20th century, he wrote about Cifuentes in the 19th. He wrote lists too: lists of street names, and neighbors’ names, and the important dates in the town’s history. I recognized in his writing a familiar feeling of responsibility for family stories and small-town landmarks and everyday people on the verge of being lost to time. He was a writer, just as I am a writer—my work, without realizing it, was a continuation of the project he began so many years ago in that Miami kitchen. That understanding was enough to make my breath catch.

From then on, I began leaning on my grandfather’s writing as I continued trudging through my own—I used his accounts of history to fill in holes and corroborate my research. I translated his words from Spanish to English and put as many of his stories as I could into my book.

He was a writer, just as I am a writer—my work, without realizing it, was a continuation of the project he began so many years ago in that Miami kitchen.

Midway through writing my book, I spent time in a library digging through boxes of Cuban archives. My grandmother had died by then, and without her physical presence on this earth the project had begun to take on an academic tone in my mind. Prior to my visit, I asked the librarian to pull anything from the archives that had to do with Cifuentes. A few boxes were waiting for me when I arrived.

I should have expected to be greeted by my grandfather that day in the library, but opening the box to see his photograph there in the brightly lit room caught me off guard. He was being saved for posterity by someone other than my family: it made my project feel, instantly and once again, both urgent and profoundly personal. There he was in black and white in his American life, a life that never strayed too far from his desire to return to Cuba. There he was in a newspaper clipping, standing with the other members of the Municipalities of Cuba in Exile, a group formed to preserve Cuban culture and fight for Cuban democracy; there were his words of encouragement and faith in the bulletin written for the exiles of the town of Cifuentes in exile. Next year in Cuba. He never got his wish, he died in Miami in 1997 nearly 40 years after he’d left home. Sitting there in the library though, I saw the immortalization of his hope.

I knew my grandmother well—we were close, intertwined. But now, I feel as if I knew my grandfather well too—or if not well, at least better. After meeting him as an adult in the archives, and meeting him as an adult through his writing, I feel a closeness between us that I never understood when he was alive. He and I have a shared love for history, a shared love for Cuba, a shared desire to put those loves together in writing and make sure the stories of our ancestors are remembered, at least for just a little bit longer. I understand us in a continuum now, split only by time: there is my grandfather writing about Cifuentes on his typewriter in the 1980s and 1990s, here I am writing about Cifuentes on my laptop in 2025.

Had we been adults alive at the same time, perhaps we would have done this work, our work, together. Maybe we would have sat side by side typing in the kitchen, maybe we would have traded documents back and forth; editing each other’s work. But in a sense, I already understand him as a partner in my writing. My work is an extension of his.

My grandfather died when I was 10, but I’m 38 now and I understand him more fully than ever. My grandfather and I are close. Our interests are intertwined.

__________________________________

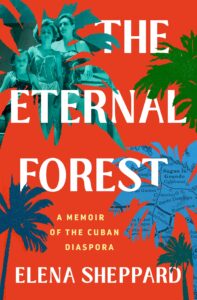

The Eternal Forest: A Memoir of the Cuban Diaspora by Elena Sheppard is available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of St. Martin’s Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan.

Elena Sheppard

Elena Sheppard is a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA, and her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Cut, The New Yorker, Vogue, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and W, as well as on NBC and MSNBC. She has been a writer-in residence at the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts, and taught creative nonfiction and journalism in Columbia’s High School Summer Program. She lives in New York with her husband and children.