How I Accidentally Became a War Correspondent

On the Journey from Kansas Wheat Fields to War-Torn Central America

When the Yom Kippur War ends, and I’m declaring my desire to stay forever on the kibbutz to anyone who’ll listen, Simcha, my adopted mother, wastes no time in setting me straight. She’s seen too many youngsters beach themselves on her shores full of similarly fuzzyheaded and romantic notions. Sure, my job picking apples in the orchards might seem fulfilling, even exotic, for now, but what will happen when the thrill of Granny Smiths is gone? “Go figure out what you want to do with your life,” she says.

Which is how, inadvertently, I find myself sitting in the coffee shop of a faded downtown hotel in San Jose, Costa Rica several years later, taking deep breaths through my mouth and trying not to become hysterical. Or pass out from hyperventilation. I’ve been working for the Wall Street Journal for barely a year, and this is the third day of my first foreign assignment. Costa Rica is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, the Journal’s two million readers back home are waiting to read about it—and I’m wondering why I didn’t choose dental hygiene as a profession.

My 11 o’clock interview, a young political scientist with stringy hair that hasn’t been washed since the time of the Spanish conquistadores, refused to talk about anything except U.S. imperialism. Then my 12 o’clock stood me up, so I went slinking back to the hotel. Its coffee shop opens onto a public square and a procession of underfed shoeshine boys who shuffle past slowly, mournfully eyeing my feet and the contents of my plate. Which only adds to my already-considerable angst.

My stringer, a brash kid from the States who does odd jobs for several newspapers and boasts an extravagant body odor, suddenly appears from behind one of the potted plants. “Tim, what are you doing here?” I say.

Tim says: “That’s a nice hello.”

“Sorry, not a great morning. Who are you here for?”

“Dial Torgerson of the Los Angeles Times. Know him?

“Not personally, but I’ve read his stuff.”

“He called yesterday from Mexico City and asked me to set up a few appointments. He’s supposed to check in around now. Wanna meet him?”

Of course I do. I’d read about Torgerson’s exploits when I was in journalism school and remember in particular how he foiled the Israeli military censors’ attempt to quash a report of war atrocities by flying to London and filing his story from there. It caused a huge furor, and his subterfuge seemed to me a noble thing, the intrepid escapade of a real foreign correspondent. Nothing like the journalistic feats I’ve racked up in my year covering agriculture out of the Journal’s Dallas bureau: reporting on sheep auctions in Oklahoma, wheezing in Kansas wheat fields, wading through rice paddies in Arkansas. It wasn’t so long ago that I was standing in corn that spread out for acres, peering through the towering stalks and trying to take notes—“green leaves, brown tassels, bugs”—when a combine harvester chugged up. The driver leaned out the cabin window and shouted: “Ever been in one of these?”

I shook my head, stunned by the machine’s size and noise.

“Well then,” he said, “hop on up, lil’ lady!”

I did, and we spent the afternoon puffing through the field, talking commodities prices, real estate, Ronald Reagan, and the soap operas the farmer watched on a tiny television mounted on the dashboard as he slayed ears of corn. I may as well have worked as a parakeet trainer, for how well those stories prepared me to cover a foreign country.

Given Torgerson’s resume, I expect to be introduced to your quintessential foreign correspondent: tall, handsome, trench-coated. Instead, I’m shaking the hand of a small, wiry, middle-aged man in a blue seersucker suit and ugly, squared-off black shoes. What hair he has left is silver, and he walks with a peculiar, slightly rolling gait. (The result, I would later learn, of a car accident that almost killed him when he was 25.) His voice is deep and resonant and lingers over each syllable like a radio announcer’s.

Dial says: “So what’s a nice Jewish girl like you doing in a place like this”?

That’s the best a wordsmith of his caliber can manage?

“Woman,” I say.

He looks confused.

“We’re called women nowadays.”

Not exactly a transcendent moment.

Still, Dial suggests that we all meet for dinner later, after I’ve finished my interviews and Tim has taken him around San Jose. I hurry out of the hotel, hail a passing taxi and stutter out an address in Spanish. I hardly speak the language. I had asked the Journal’s foreign editor for lessons to burnish my high-school Spanish, but he refused, offering French instruction instead. When I pointed out that Spanish was generally recognized as the region’s language, the editor—known throughout the paper for his idiosyncrasies—narrowed his eyes. “Schuster,” he said, “the idea is to maintain a certain distance from the story.”

I’m not sure he intended that space to be the size of the Grand Canyon.

The cab crawls through downtown San Jose’s narrow, crowded streets. We pass vendors hawking lottery tickets, pyramids of fresh papaya, cups of crushed ice drowning in tooth-dissolving syrups. There are boxy little houses, colored pink and blue and framed by orange and purple bougainvillea. Converted U.S. school buses, the main mode of public transportation, are painted brilliant reds and indigos with eyes, eyelashes and mouths drawn on the front fenders, giving them the look of motorized drag-queens. Just what I wanted, I think, so why am I not enjoying this? My mind shifts back to my little outburst of bravado with Dial at the hotel; that’s what happens when you feel like a fraud. Or like a toddler: a toddler stuck in her Terrible Twos, desperately wanting to take control of her world, but lacking the experience and confidence to lurch bravely forward. While clad in a disposable diaper.

Fraud or toddler, I had never seriously considered journalism as a profession. My embrace of it happened almost as a fluke. Following Sim’s admonition, I wound up at a Midwestern university, one sufficiently distant from Mom so that I couldn’t easily go home on weekends. I knew what I wanted: a life that would allow me to see the world and witness history in the making. How to get there, having neither sugar daddy nor personal genie, was another matter.

Still thinking I’d go back to Israel, I majored in Near Eastern studies and in my last year applied to a doctoral program. Not long after receiving my acceptance letter, though, I awoke one night hyperventilating: I was too young to die in academia. Chickening out like that at the last minute certainly made me feel better, but it also made me lose all my scholarship money. Now I needed to learn a trade to support myself—and fast. That’s when, flailing about for an alternative, I stumbled on a description in the university course catalogue for a Master’s degree in journalism: no prior experience needed, plenty of spaces still available, two years of studies and you’re out covering the world.

The head of our program, a small, balding man who had worked for one of the newsmagazines when people still read them, would hear me moaning that I didn’t know what to do about a particular source or a hole in my story and bark, “Do everything, Schuster!” But here’s the thing about journalism that amazed me: people want to talk to you. (Unless, of course, it’s a perp or celebrity, in which case your right hand will forget its cunning and your tongue cleave to the roof of your mouth before you’ll get any quotes.)

Whoever figured out the psychology of journalism all those centuries ago was brilliant: it succeeds by tapping into some very basic human traits, like a person’s sense of injustice. Or his ego. Or his desire to avoid doing work. Whatever the reason, people wanted to tell their stories. And once they got going, they would often confide remarkable things having absolutely nothing to do with the topic at hand: how interesting urology seems, for instance, or that a friend’s friend let her pet pig sleep in bed with her—when all you really needed was a quote about the new County Commissioner.

I loved it. I loved everything about it: the reporting, the writing, the opportunity to see and learn about new things. How could I not?

*

After school I looked for a job. I sent my clippings and job-application letters to 43 newspapers and received 42 rejections. I was resigning myself to a life on the local shopping news when the 43rd newspaper I’d applied to, the Wall Street Journal, which back then prided itself on molding promising young journalists, offered me a job. Police beat be damned; the editors liked my stories.

During my interview in New York with the paper’s high priests, when they asked which of the Journal’s many bureaus most interested me, I said: “Oh, I don’t want to work domestically. I only want to be a foreign correspondent.” They nodded understandingly, and promptly dispatched me to their outpost in Dallas—which, to a New Yorker, probably is foreign. Right off the bat, the bureau chief didn’t trust me. The woman I was replacing went to the same university as I, had swanned around the office saying that she only wanted to be a foreign correspondent and—wouldn’t you know it?—quickly got hired away by a newsmagazine to work abroad. I must have seemed a clone of my predecessor to the bureau chief, a Journal lifer who viewed defectors from the paper as deserving of a firing squad without the blindfold. Every story I proposed was suspect, as if writing about an air conditioning repairman in the midst of a crushing heat wave were really a ploy, somehow, to become Beijing bureau chief for the New York Times. His antipathy was such that after doling out the sexy business beats—highly valued at the paper—to the other five reporters, the bureau chief told me to come up with my own. That’s when Neil, a former bureau chief himself who had been demoted to lowly reporter and stewed at the ignominy of it in the cubicle next to mine, suggested agriculture. “Go cover shit, Schuster,” he said, “it’s a great story.”

Then—as often happens in this kind of tale—I got a break. For reasons shrouded in obscurity and time and the paper’s only grudging interest in stories not having to do with money, the Dallas bureau was responsible for reporting on Central America. The correspondent who covered it abruptly got transferred to Los Angeles; and the other reporters were engrossed in their business beats, which they didn’t want to relinquish.

“You’re the only one left,” the bureau chief said generously. “Besides, I know you’d kill for it.”

Oddly, I wasn’t so sure. These were the early days of the Reagan administration, when the U.S. was becoming deeply involved in the region’s conflicts, providing overt and covert aid to help defeat communist guerrillas and governments backed by the Soviet Union. Which meant that with barely a year’s reporting experience, I was suddenly responsible for one of the hottest foreign stories of the decade and competing against the heavy hitters of my profession.

Now that I truly had to deliver that fueled my indignation at being rejected for jobs melted away. Maybe the editors at those 42 newspapers were right, I thought. Winter wheat was one thing, but an entire region rapidly becoming engulfed in war?

__________________________________

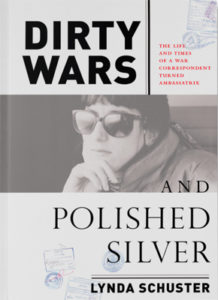

From Dirty Wars and Polished Silver: The Life and Times of a War Correspondent Turned Ambassatrix. Used with permission of Melville House. Copyright © 2017 by Lynda Schuster.

Lynda Schuster

Lynda Schuster is a former foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal and The Christian Science Monitor, who has reported from Central and South America, Mexico, the Middle East, and Africa. Her writing has appeared in Granta, Utne Reader, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times Magazine, among other. She lives in Pittsburgh with her husband and daughter.