How Hurricane Sandy Turned Regular People Toward Radical Solutions

Elizabeth Rush on the Importance of Testimony in the Aftermath

Towards the beginning of my work on Rising, I interviewed a young woman named Nicole Montalto about her Hurricane Sandy experience. She lived in a low-lying, right-leaning, working-class neighborhood along Staten Island’s eastern shore where residents were asking the state to bulldoze their homes and allow the land to return to nature.

What, I wondered, did Nicole and her neighbors know that the rest of us did not? How was it that they were interested in retreat, one of the most progressive and controversial climate change adaptation strategies? Nicole and I spoke for hours in her Aunt Patti’s spare bedroom on the two-year anniversary of the storm. As I listened, I thought to myself that Nicole’s words needed to enter into Rising untranslated; no amount of essaying on my part would add anything to the story she told.

I went home and transcribed the interview and a few months later discovered Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl, which recounts the nuclear disaster and its aftermath entirely with the words of those who lived through the event. This style of writing is called “testimony,” and writers from Belarus to Guatemala employ it. While only bits and pieces of Rising embrace this form, it is my hope that the sections that do will carry readers closer to those living alongside our transforming coastline and allow us, if only briefly, to stand in their soggy shoes. This is important because it is a position more and more of us will occupy in the coming century. Listening to Nicole, I learned that coming to let go of the places we call home might just end up being a radical form of resiliency.

![]()

Nicole Montalto

Oakwood Beach, Staten Island

I was living at home at the time of the storm. I was working at a dentist’s office and living at home. Of course I had my own bills, like my cell phone bill and my car insurance, but I didn’t have a mortgage and I didn’t have to pay utilities. I stayed with my father because I needed to save money. He was never the type of guy who would call out for help. If something needed to be done, we just did it. We figured it out.

My father lived in that house since he was six. He bought it from his father in 1984, around the same time he married my mother. When I was little there weren’t as many houses and the wetlands were larger. We all had the same bus stop; we all went to the same school. Me and my sister were big into playing soccer and kids from the neighborhood would come over ’cause ours was one of the bigger yards.

Even as we got older, if my friends got in trouble and needed a place to crash, they came to us. Sometimes my dad would bust our chops about things, like, “All right, your friend has been sleeping on the couch for three days now, what’s going on?” But mostly he was cool. Katie—she’s my best friend to this day—she would call sometimes just to speak with my dad. He would shoo me away from the phone and I could hear her saying something like, “My brakes aren’t working right,” and my dad would tell her to bring her car over, that he would fix it for her.

I am 26 now; I was 24 at the time. The year before, with Irene, the press and everyone made it up to be a huge thing. My sisters and I, we brought the animals to my mother’s apartment in Annadale. I had a dog that was so old—he was blind and deaf—that I felt bad moving him. But Irene was nothing, nothing happened. With Sandy they were making an equally big deal, and you know, some people were taking it seriously, some people weren’t. My dad being one of those people. We thought it would be the same thing as the year before.

I’m not really an anxious person, but for some reason I was fidgety the day before the storm. I even packed a bag, just in case we had to get out quick. I put clothes inside ziplocks, I put my electronics in there in case I was bored, and I packed another bag for the animals. I didn’t sleep much.

Around ten o’clock that Monday morning, I called my dad because the backyard started to flood. He decided to come home early from work. Flooding wasn’t the most uncommon thing. There was a certain part of my yard that got wet—but it had to be a lot of rain.

“I’m not really an anxious person, but for some reason I was fidgety the day before the storm.”

He came home and me and him started doing rundowns. We went through the garage and basement, asking, Is there anything in here that we should bring up higher, just in case? My older sister’s room was in the basement, so we put some stuff up on shelves. I remember moving her clothes, electronics, things like that. The rest of the rooms were upstairs. That was where the things of real value were. We brought the cat litter up because that’s something you really don’t want floating around.

My little sister is a bit of a nitpicker. I was like, “You know what, let me bring you to your friend’s house.” If something was to go down, me and my dad would be OK. Whereas with my little sister I felt like we would have had to smack her, put her in the car, and go. She had a friend, Frankie, that was home, and he was up high on a hill. I drove her there at 1:00 pm. My older sister was at work or at her boyfriend’s or something. So it was just me and my dad the rest of the day. It was like a regular day. Actually, because I hadn’t slept the night before, I took a nap.

I woke up and the storm had started. It was getting dark. My father was going to run for president of the postal union that year. And that was what he was doing; he was on the computer typing up the speech. There was one small desk lamp on. I remember a tree falling on the other side of the garage. We watched it and were totally nonchalant about the whole thing.

My neighbor across the street, my aunt Patti’s daughter’s husband, came running over around seven. “It’s flooding fast, it’s up to my ankles now,” he said. I really didn’t plan on leaving, but there was this panic in his voice. That was when my dad was like, “You gotta go.” What we had done, actually, was I had parked my car up where I thought it was safe from the water, about a mile away. My backup plan was to go to my mom’s. My dad didn’t really get along with my mom’s sister, so his whole thing was, “I’m not leaving.” He said, “You know, I just want to make sure the pump is working.” That the electricity was off. All those things you think about when it floods.

At that point he was like, “You gotta go, you gotta get outta here.” The assertiveness in his voice told me it was a no-joke sort of thing. He said, “Take my car; go to your mom’s.” I was worried about the animals. But my father said he’d take care of them. By the time I left, I had just enough time to get the car out, because on Mill Road it was deeper than at my house by a couple feet at least.

I went out the one way. My dad yelled out the door, he was like . . . [Interrupts herself.] I don’t like to talk about this stuff, I rarely ever do. [Crying.] Sorry. This is why I don’t do interviews. But you’re writing a book, and that’s different because it will immortalize him.

He yelled out the door, “Don’t hit the brake, just slam on the gas!” So that’s what I did, I just took off. If he hadn’t said that, I might have hit the brakes and gotten stuck five seconds from my house.

I slammed on the gas and went flying through the water.

There was a huge tree down on Guyon Avenue. I had to take side streets just to go around it. I got to my car and I called him. To say I made it, I’m driving now. I told him there was a tree down but he sounded preoccupied. He said it was a good thing I got out when I did. “The water is rushing in,” he said. “I gotta go, I gotta go,” and he hung up.

I got to my aunt’s. If I had to guess the time, I probably left around 7:30, and that was when the water was suddenly getting pretty deep. I probably talked with him at 7:35 and he said the water was coming in the basement. Maybe I got to my mom’s at 7:50. I had only been there for 20 minutes or so. My sisters started calling me, and they kept saying, “I haven’t been able to get in touch with Daddy! I haven’t been able to get in touch with Daddy!” And I was like, “OK, let me call him.” I had known that he was doing something at home, so I didn’t want to call him right away. Then I tried calling him and calling him. I started texting him. “Just let us know you’re OK.”

There was no response. I told them that if by 8:30 he doesn’t get in touch I would go back. When 8:30 came around, the storm was really bad. So I decided to give it another half an hour. But at a quarter to nine I had to go. My mom said she would come too. The weather was crazy. There were trees down everywhere. I couldn’t even get to Hylan Boulevard because there was so much water. I had Nike thermal pants and all of these tight thermal clothes, boots, everything. I knew I was going to have to tread through water. I was prepared. So I told my mom to wait in the car, I was going to see how far I could get before the water got really high. I didn’t even get to Hylan Boulevard before the water was at my waist. I was still well over a mile from my house. I can’t swim a mile. If it was at my waist and I didn’t even cross Hylan, I couldn’t imagine how deep it was over there.

“I went into my house; I was screaming for my dad. Everything was upside down.”

We ran into this cop and he said that T-Mobile was down, that there were power outages everywhere. I was like, “Oh, that makes sense as to why my dad didn’t answer his cell phone. OK, thank God, maybe he’s all right.” The cop told me that there was a back way that I could get closer to my house, down Tysens Lane. It was clear. They had electricity over there. It was like a whole other world. I went down Tysens, I went down Falcon, and I parked as close as I could. It was 9:30 or 10:00 and the water had started to recede a bit. There was a bunch of fire trucks and cops. They didn’t know what to do. Nobody expected it to be as bad as it was. As I was walking by, nobody said anything to me. They didn’t care that I was walking into the water.

I got to the point where the tree was down, so I was getting closer to my house. There were parts where I was on flat ground, parts where the water was up to my knees and my waist, then flat again. But when I got to the tree, you could see that the water was deep over there. I had all intentions of just going.

In the first flood [the Nor’easter of 1992] my uncle Charlie got me out of my house by putting me on his shoulders when the water was up to his chest. One of the things he had said is that you can’t walk in the middle of the street because the manhole covers get blown off during the flood, and then you can get sucked down into those open holes as the floodwaters recede. I didn’t think about it at that point. I would have walked down the middle of the street, not thinking about it at all. But there were three guys about to go and then suddenly they were like, “Oh no, forget it.” It made an impression. One of them had said, “No, you’ll get killed, you’ll get killed. The manhole covers.” I remembered my uncle Charlie then and I didn’t go. I just stood there.

You would see random people running out of the water, going different ways. I kept asking if there was any way to get to Fox Beach Avenue and everybody said there was no way.

I had to turn around and go back to my mom. I told her that it was beyond my capabilities. It’s one thing to swim a little and another to swim over half a mile. I’m not sure if you know my uncle’s story. He stayed on a neighbor’s roof for four hours. You know, in a situation like that, when you have no options—maybe. But why would I walk into it?

It had stopped raining at that point. I walked back to my car and drove to my mom’s. My mom and I slept in the same bed, but all I could do was worry. The next day at 7:00 am., I was like, “OK, the sun is up, we gotta go.” And we did, we went out there. It was insane. Everything was turned over. The watermarks on the homes were so high.

I went into my house; I was screaming for my dad. Everything was upside down. The couches floated to different areas, my bed was up on the wall. The only things that didn’t move were my dining room table and the filing cabinet, because both were too heavy. That was where my dog took sanctuary, on the filing cabinet. My cat was sitting there on top of my bed. I didn’t see my dad. I thought, “Shit, maybe he left. Maybe he went to someone’s house.” But then I thought, “He wouldn’t leave the animals.”

At that point I could actually see the water in the basement. It was still so high. There was maybe at least four and a half feet down there. I was yelling for him. But the only thing I could do was get the animals out. I threw the cat into the carrier and I took the dog under my arm. I went to my mom and told her I couldn’t find him.

Nothing was working. From that point on, we went crazy trying to find my dad. Everyone was calling hospitals and precincts. That was Tuesday. We thought maybe he hit his head and forgot who he was. Maybe he was in a hospital as a John Doe. It started to get really cold. We thought, you know, god forbid he was wet, had hypothermia, got dragged away into the weeds.

My dad’s wallet was still in his room. There was something else too that he left behind; I don’t remember what it was. The wallet was the biggest thing—it had money and his ID. He wouldn’t have left the house without those things. Oh, I know what it was. He was on and off with smoking cigarettes—I’m the same way too. And he had left his pack at the table and a cup with a couple of butts though we never smoked in the house. It is so weird to timeline things. I spoke with him on the phone. He said it was good I got out when I did. The water was rushing in. He was on the basement stairs when he was on the phone with me. Did he come back up, and smoke two cigarettes? Was that before or after? I saw these things that were clueing me in to the idea that he never left the house. When I started seeing those things, I went down to the basement and began screaming. I was hoping that I would hear him but at the same time I wasn’t.

The walls in the basement were all down. Everything was everywhere. There was a washing machine in front of my face, I could see into my sister’s room. There was no way I could walk through. Everything was in the water, floating. I believe that the water came in one big force. [Silence.] It’s the only thing that makes sense to me.

“People buy what they can afford. The problem is that the builders build these homes and the city allows it just to make some money.”

My dad’s friends, once they knew he was missing, they broke all the windows in the basement to get the water out. They started pumping the water too. People say he was down there for the pump, but I don’t see how it could have been the pump, because the basement was already flooded. What the hell could a pump do? When we pulled up on Wednesday morning, my father’s friend told us that they’d found him. My father was in my sister’s room in the basement.

My mom had to go identify the body; even though they were divorced they remained close. She said he had a gash on his head, so what we believe, or what we hope happened, is that he was knocked unconscious. A force of water must have knocked a piece of furniture on him, or knocked him off his feet.

My boyfriend and I had planned on moving into the basement, to live there together, renovate it, and save up money so we could buy our own home. We didn’t look for apartments right away because we had to plan the funeral. By the time we got around to it everything was rented out. So we talked my mom into getting an apartment with us, and a year later we ended up buying a two-family home in Stapleton Heights. It’s still my mom, my sister, my boyfriend, and I, but we have separate doors now.

After the storm we were all like, “We’re moving to a hill,” and I moved to a hill. By the time I was 26, I lived through two floods, one of which took my father’s life.

I hate when people write comments like, “Well, you shouldn’t have lived there in the first place.” Of course if we knew, we wouldn’t have been there. People don’t move into these places thinking, “Living here I might lose my life.” No, there are builders who buy the lots and then they sell them and they spin it and you think you are living in a fine house. People buy what they can afford. The problem is that the builders build these homes and the city allows it just to make some money. They took a spot where the water used to be absorbed and they paved it. What they should have done is left it alone. I mean we were right in the middle of a wetlands. And then for people to condemn us for buying the homes, they need to get a life and shut up. That pisses me off more than anything. That’s why I don’t like doing these interviews: because it puts me out there and it puts my family out there. I have heard people say comments with my father’s name in their mouths. I’m not going to get into an argument online, but I see these comments and it hurts.

It’s tough to see this neighborhood that I grew up in, that my father grew up in, that my sisters grew up in—I mean, we spent our entire lives there—being demolished. But on the other side, it’s nice knowing that this is to protect everyone else and that it can’t happen again. At least it can’t happen to the people I know and the people I love. And maybe the government really will do the right thing and let Oakwood go back to nature.

Home was that house—it was my dad, it was my mom, it was my sisters. When my dad was gone, it wasn’t home anymore.

We’ll hang out here at my aunt Patti’s for a little while longer. [It is the second anniversary of her father’s death.] I’ll eat lunch, go home, change, put something in the slow cooker. But the plan is to go to my old house later, one last time before they tear it down. My boyfriend and I, we spent Sunday afternoon cutting down the weeds over there. Someone wrote an article about how they are boarding up all the homes in Oakwood and demolishing them and my house is the first picture. I was so embarrassed, because our house looks terrible. Last year we went there as well, we went there and had some beers and we got together to celebrate his life.

My dad used to play guitar and someone had a disc of him playing. My little sister and I haven’t looked at the home movies yet.

We haven’t been able to watch them, but we dried them in rice. So that night—a year ago today, actually—was the first time we heard my father’s voice, and we cried but it was nice, it was really nice. He was singing and playing the song he always used to sing: “Wild Horses.”

__________________________________

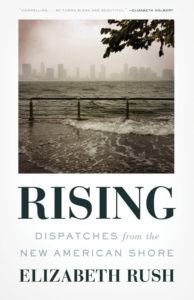

From Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. Used with permission of Milkweed Editions. Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Rush.

Elizabeth Rush

Elizabeth Rush is the author of The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth and Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Rush’s work has appeared in a wide range of publications from the New York Times to Orion and Guernica. She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Science Foundation, National Geographic, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Howard Foundation, the Andrew Mellon Foundation and the Metcalf Institute. She lives with her husband and son in Providence, Rhode Island, where she teaches creative nonfiction at Brown University.