How Huey P. Newton’s Early Intellectual Life Led Him To Activism

Mark Whitaker on the Making of a Modern American Revolutionary

For Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, Telegraph Avenue was more than a four-and-a-half-mile road stretching north from their hometown of Oakland to the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. It was a link between two distinctly different worlds: between the rough ghetto streets where they grew up, and the steepled academic sanctuary so close by.

For much of the early 1960s, what existed of a Black student movement in the San Francisco Bay Area was organized by activists from Berkeley, and Newton and Seale, part-timers at a junior college in Oakland, followed the lead of those self-important, middle-class leaders. But that began to change for good on the evening of Thursday, March 17, 1966, when Newton and Seale and a friend they called Weasel took a walk up Telegraph Avenue to look for secondhand albums by bluesmen T-Bone Walker and Howlin’ Wolf at a record store near the university.

Walnut dark, with a protruding brow, heavy eyebrows, and a thick mustache, Seale, at age twenty-nine, looked the tough guy part of a metalworker who had served in the Air Force and been court-martialed for a confrontation with a colonel. But Seale also had a theatrical streak, with a sideline as a stand-up comedian and a knack for memorizing and reciting poetry.

As the threesome proceeded up Telegraph Avenue, his companions urged Seale to entertain them with one of his favorite poems, written by a fellow student at Oakland’s Merritt College, Marvin Jackmon, a pioneer of the Black Arts Movement who went by the pen name of Marvin X. Entitled “Burn, Baby, Burn,” Marvin’s composition told the story of 1965 Watts riots in the style of the Beat poets.

Anytime [Seale] got into trouble, he wanted his friend Huey Newton by his side.

Loud enough so that passersby stopped to listen, Seale recited jagged verses that began with an expression of Black weariness…”Tired. / Sick an’ tired / Tired of being sick an’ tired…” and ended with an expression of the pent-up fury that had been unleashed on the Los Angeles police and their imperious chief, William Parker: “Motherfuck the police / Parker’s sista too… / Burn baby burn / In time they will learn.”

As the trio neared the Berkeley campus, Seale summoned another poem from memory, an anti–Vietnam War diatribe called “Uncle Sammy Call Me Fulla Lucifer” by a street poet named Ronald Stone. By this time, so many onlookers had gathered that Weasel borrowed a chair from a restaurant patio so Seale could climb up and address the crowd. The spirited performance drew calls for an encore, and Seale repeated the draft dodger’s lament: “Uncle Sammy don’t shuck and jive me/ You school my naive heart to sing/ red-white-and-blue-stars-and-stripes/ songs…”

Just as Seale reached this point in the poem, an off-duty police officer named George Williamson emerged from the crowd.

“You’re under arrest,” Williamson announced.

Seale climbed down from the chair. “What are you talking about, ‘You’re under arrest’?” he asked. “Under arrest for what?”

“You’re blocking the sidewalk,” the policeman said.

“What do you mean I’m blocking the sidewalk?” Seale protested. “I’m standing over here.”

Three more policeman appeared and tackled Seale to the ground. Out of the corner of his eye, Seale saw Huey Newton, his baby-faced friend, throwing punches, several of which landed on the side of a policeman’s head. Seale squirmed loose and a brief tussle took place before the officers subdued the two men and arrested them for disturbing the peace. At the police station, Newton and Seale phoned a friend at a campus group they belonged to, called the Soul Students Advisory Council (SSAC), and arranged to borrow $50 to post bail.

A few weeks later, Newton and Seale were driving around Oakland when they saw another police officer arresting a Black man on the street for no apparent reason. Newton wanted to jump out of the car and confront the cop on the spot, but Seale held him back. Instead, the two went to the SSAC office, got more cash, then proceeded to the police station and posted bail for the arrested man, who was so grateful that he broke down in tears.

Along with the Telegraph Avenue incident, the experience of bailing out the stranger led Seale to two conclusions. The first was how much more satisfying it was to stand up to police harassment and provide assistance to Black folks on the streets of Oakland than it was to engage in windy intellectual debates with other college students. The second was that anytime he got into trouble, he wanted his friend Huey Newton by his side. Newton “doesn’t let anybody mess over his partners, or whoever he’s running with,” Seale recalled with admiration. “That’s the way he is….That’s the way he gets with any human being who tries to hurt him or his friends. And his people and his family. That was a big thing.”

Newton was also the more visionary of the two, the one who kept raising the idea of creating a new organization.

A casual observer of the two might have been surprised that it was Seale who looked up to Newton. Seale was the older one, by more than five years, the Texas-born military veteran and skilled mechanic who had worked in factories that supplied sheet metal for the Gemini rockets. He was more physically imposing, standing several inches above Newton’s slight, five-foot-seven-inch, 130-pound frame. Seale was also the extrovert, the actor in campus plays and performer in Oakland’s coffeehouses—compared to Newton, who was shy and hated speaking in front of crowds.

But Newton was the tougher fighter, with lightning-quick hands and a fearless readiness to take on all comers. He was the deeper thinker, a self-taught reader who had introduced Seale to the French existential philosophers Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre and helped Seale understand Frantz Fanon, the French African psychiatrist and author who saw armed rebellion as a path to psychological liberation. Newton was also the more visionary of the two, the one who kept raising the idea of creating a new organization that could appeal not just to privileged college students but to the sort of struggling Black folks the two had grown up with in the Oakland ghetto. The “brothers on the street,” Newton called them.

*

It was Newton’s family, and his place in it, that accounted for this unique combination of traits. His father, Walter Newton, was a mixed-race, Alabama-born jack-of-all-trades laborer and Sunday preacher who married his mother, a Louisiana native named Armelia Johnson, when she was just seventeen years old. When the couple’s seventh and last child was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on February 17, 1942, Walter chose the name Huey Percy Newton, after the state’s former governor, Huey Pierce Long. History would remember Huey Long by his nickname, the Kingfish, and his fiery populist appeal to Southern whites.

But Walter Newton admired Long for the sly, roundabout way the governor sometimes turned the racist Jim Crow system to the benefit of Black people. When Huey was a boy, Walter told him the story of being in the front of a crowd when Long gave a speech decrying the fact that white nurses had to treat “half-naked” Black men in the state’s hospitals. A frenzy ensued that led to hospitals hiring more Black nurses to tend to Black patients. “My father believed that Huey P. Long had been a great man,” Newton recalled, “and he wanted to name a son after him.”

In his father, Newton had the rare example of a Black man of his generation willing to stand up to whites in the South. Wiry and stern-looking, with pale skin, piercing eyes, and a brush mustache, Walter taught his children that “you can take a killing but you can’t take a beating.” Huey grew up hearing accounts of his father’s stubborn bravery. In one often told story, Walter publicly accused a white businessman of cheating him.

When the angry merchant appeared at the family’s house, Walter calmly walked out and sat on the running board of the man’s car, knowing the glove compartment contained a gun. “If you hit me a lick, the other folks will have to hunt me down because you’ll be lying in the road dead,” he warned the merchant. For Huey, his father’s mystique was made all the more powerful by the shadowy circumstances of his birth, to an unwed Black woman and a white man in the brutal era after Reconstruction. “My father’s father was a white rapist,” Newton reported on the first page of his autobiography, later reflecting that Walter’s mixed blood may have served as a shield in the South, making white men reluctant to attack someone who looked so much like them.

Yet Newton also learned another lesson from his father: about how difficult it was for a Black man with little education, no matter how honest or hardworking, to provide for his family. In Louisiana, Walter labored in a sugarcane mill, at a carbon plant, and as a railroad brakeman, stopping only on Sundays to preach at the local Baptist church.

In 1945, when Newton was three years old, his father moved the family to Oakland just as the war was ending and California’s defense plants were closing. Walter had to resort to odd jobs as a brickmason, plumber, and carpenter while the family moved from one tiny two-bedroom apartment to another. Often, the children subsisted on a daily diet of “cush,” a dish of fried leftover cornbread mixed with gravy and onions. No matter how scarce money became, however, Walter always insisted on paying his bills on time. He dispatched his sons to deliver checks to his creditors in person so they could bring back stamped receipts. “My father’s constant preoccupation with bills is the most profound and persistent memory of my childhood,” Newton recalled. “For me, no words on the street were as profane as ‘the bills.’ It killed me a little each time they were mentioned, because I could see the never-ending struggle and agony my father went through trying to cope with them.”

From his mother, Newton received lighthearted relief from the family stresses and encouragement for the sensitive and creative side of his personality. Still barely out of her teens when her children were young, Armelia often seemed more like a playmate than a mother, leading them in laughter-filled games of jacks and hide-and-seek. Early on, she recognized an artistic bent in her youngest child, and got him started on piano lessons that he continued for seven years.

By junior high school, Newton was introducing friends to recordings of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee. As a way of overcoming his shyness with girls—and covering up for a learning disability that kept him from mastering the skill of reading by sight—he memorized poetry. He was able to recite entire poems by Edgar Allan Poe and T. S. Eliot, as well as passages from the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám and the “tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” soliloquy from Macbeth.

From his older brother Walter Jr., meanwhile, Newton learned to use his fists. As early as kindergarten, students had started taunting Newton for his “too pretty to be a boy” baby face, and for the middle initial he included when announcing his name. “Huey Pee Newton,” they chanted. “Huey Pee goes wee, wee, wee.” At first, Newton responded to the bullying by pretending to be sick so he wouldn’t have to go to school.

But the Newton family had a tradition that older children looked after younger ones, and Newton was “given” to Walter Jr., the second born, known to everyone as Sonny Man. Sonny Man started taking his little brother to school—and teaching him how to fight back when he was picked on. By elementary school, Newton had “the fastest hands on the block,” he recalled. He became champion of the pretend prizefights that Black boys staged on Oakland street corners, boxing with towel-wrapped hands while winos placed nickel bets and rewarded the last one standing with a box of Cracker Jack.

In his father, Newton had the rare example of a Black man of his generation willing to stand up to whites in the South.

Walter Jr. was also a hustler—a pool shark, gambler, petty thief, and ladies’ man who took the lesson from his father’s struggles that honest work was a sucker’s game. By the end of junior high, Newton began to take after Sonny Man in that respect, too. He joined a dice-playing, parking-meter-cracking gang called “The Brotherhood” and, at age fourteen, spent a month in Juvenile Hall after an arrest for carrying a gun.

For high school, Newton went to Oakland Tech, an imposing institution on the city’s north side with large white columns and a distinguished roster of white and Black graduates that would include film star Clint Eastwood, baseball great Curt Flood, and Ron Dellums, the city’s future mayor and U.S. congressman.

Because of his struggles with reading, however, Newton scored only a 78 on a Stanford-Binet IQ test, the intelligence exam schools used to track students. He was placed in “slow” classes whose teachers made no effort to relate coursework to the lives of inner-city teenagers. “My high school diploma was a farce,” Newton recalled. “When my friends and I graduated, we were ill-equipped to function in society, except at the bottom, even though the system said we were educated.”

Fortunately, Newton had another older brother who exerted a more positive influence. Melvin Newton was the second youngest child in the family, four years older than Huey, and the most studious. It was Melvin who introduced Huey to poetry, and taught him hypnosis, a skill that Huey used to impress his friends by putting them into trances and making them bark like dogs.

When Melvin graduated from high school, he continued to live at home while enrolling at Oakland City College. In high school, a guidance counselor informed Huey that he wasn’t “college material,” but watching Melvin pore over his philosophy and sociology books gave Huey other ideas. If he wanted to follow his brother’s footsteps, Huey realized, he would need to learn how to read properly.

So one day, he borrowed Melvin’s copy of Plato’s Republic and a dictionary. For several months, Huey spent hours each day slowly making his way through the dense text. He looked up words in the dictionary, sounded them out, then pieced together sentences and trained himself to scan paragraphs. Finally, like the prisoner freed from the cave in Plato’s allegory, he was able to grasp the meaning of what had once looked like only shadows on a page.

__________________________________

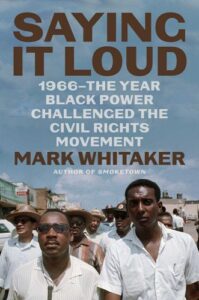

Excerpted from Saying it Loud: 1966—The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement by Mark Whitaker. Copyright © 2023. Available from Simon & Schuster. Printed by permission.

Mark Whitaker

Mark Whitaker is the author of the critically acclaimed memoir, My Long Trip Home, and Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance. The former managing editor of CNN Worldwide, he was previously the Washington bureau chief for NBC News and a reporter and editor at Newsweek, where he rose to become the first African-American leader of a national newsweekly.