How Horseback Riding Helped Barbara Stanwyck Rise Above Hollywood Misogyny

“Her career as a rider is studded with falls, which she came to incorporate into her star persona as a wannabe stunt performer.”

“No animal was harmed” … serves a taxonomic purpose, separating the two principal film genres, fiction and documentary…. Why aren’t similar reassurances applied to human beings?

–Akira Lippit, “The Death of an Animal”

*Article continues after advertisement

Akira Lippit continues this thought by reference to the prolific representation of violence against men and women in fiction films and suggests that the “human counterpoint to this disclaimer” is “all resemblances to persons living or deceased is purely coincidental.” And yet much violence is often meted out against actors on sets—and not simply psychological violence.

Barbara Stanwyck was frequently injured in film shoots, and she wore it more as a badge of honor than a grudge, as evidence of her hardiness and professionalism. Her body was arguably a site of struggle, as she repeatedly put it on the line as a mark of sincerity and action. Aligning her body with nature, she gained some distance from the glamour of Hollywood culture while challenging gendered conventions of movement and stasis.

Looking at some of Stanwyck’s many horseback-riding scenes, it is clear that the strong, dynamic imagery of riding enabled her to rise above the entrenched misogyny of the industry. Certainly, those images have outlasted the culture in which they were produced, offering another image of a woman on the 20th-century screen. At the same time, the transcendent, enabling, independent image of horseback riding was produced within an industry of illusion and deception.

When the spectacle is conjoined with anecdotes and trivia pulled from biographies and industry files, the scene of gendered labor and sexist critical discourse is not so pretty. The pleasures attached to genres like the western need to be unpacked so as to understand that, as Lauren Berlant puts it, “freedom is not freedom, pleasure not disavowal not disavowal, but ways we have learned to identify knowledge and sensation.”

In an early scene in Forbidden, Stanwyck is briefly seen riding a horse on a beach in a dazzle of sunlight. In profile her hair flies behind her as the camera tracks beside her fast-moving silhouette. It’s a remarkable image of freedom and transcendence, unique in her career in its speed and cinematic energy. The scene is quickly inserted into a long and rambling story about a fallen woman, and it seems to carry the full weight of the height from which she falls.

The scene is supposed to be Havana in the moonlight, where her librarian character, Lulu, has gone to find romance and excitement. She finds only Bob (Adolphe Menjou), who turns out to be married. In this, one of her first films, the novelty of the sparkling image might be seen as symbolic of the promise of Stanwyck’s stardom. If so, her career as a rider is studded with falls, which she came to incorporate into her star persona as a wannabe stunt performer. Horseback riding in westerns frequently took Stanwyck out of Los Angeles to shoot on locations and landscapes that she came to love. After her death, her ashes were given to the wind at Lone Pine Desert in the High Sierra mountains—a long way from the streets of Brooklyn.

We know how often her power and independence are curtailed by the requisite happy endings of heterosexual romance.

In fact, the beach scene in Forbidden was shot in Laguna Beach in Southern California at sunrise, and a double took Stanwyck’s place for the long shots. Shooting the close-up, Stanwyck was thrown by the horse and badly injured, although she stoically completed the picture despite spending each night in traction in a hospital. She had already seriously injured her back when the set collapsed shooting Ten Cents a Dance and continued to work with excruciating pain, setting a pattern that would continue throughout her career.

Stanwyck was said to be “scared of horses” in her early career, although Victoria Wilson’s biography has her romping about Central Park in the 1920s with her girlfriends and hanging out in cafés wearing riding breeches. She is seen on horses in The Woman in Red (1935), Annie Oakley (1935), and A Message to Garcia (1936), but in 1938 she had a clause added to her RKO contract protecting her from riding on camera after her good friend Marion Marx had a bad fall from a horse.

Stanwyck built and co-owned a ranch named Marwyck near Van Nuys just outside Los Angeles with Zeppo Marx and his wife, Marion, from 1935 to 1940, where they raised thoroughbred horses. She and Robert Taylor were frequently photographed at the racetrack during this period, and they did many photo shoots at Marwyck with and without Stanwyck’s son, Dion. In this way horses became integral to the “happy family” imagery that Stanwyck managed to orchestrate for a brief period of time. It was probably during the years when she lived at Marwyck that she improved her riding skills and overcame any fears she may have had.

By the 1940s she had gained a reputation as an expert horsewoman. When screenwriter Nivel Busch visited the set of The Furies, he complained, “They put Stanwyck on a miserable fat-assed palomino that could hardly waddle.” She was a good horsewoman, according to Busch, but they thought she would fall off a more energetic horse and endanger the production. Nevertheless, her rejection of stunt doubles inspired John Houston to do the same, not to be outplayed by a woman.

There is a kind of inner tension between Stanwyck’s affinity for dangerous riding and the tendency for her characters to fall off their horses, just to be saved by men.

Stanwyck’s repeated claim in the latter part of her career that she wished she had been a stuntwoman is in keeping with her early career desire to emulate Pearl White, an action heroine of the teens. Her horsiness undoubtedly abetted Stanwyck’s “tough” image and made her an icon of a so-called powerful woman in the postwar years. A horse makes a small woman appear large, her mastery of the animal is symbolic of control and dominance, the aura of nature cuts through the artifice of glamorous stardom, and the lone horsewoman is iconic of the “independence” label that the actor earned by other means in the 1930s.

Horses eventually became an essential element of Stanwyck’s star image, and yet viewing footage of her on horseback, we can’t always be sure if it is Stanwyck, as doubles were frequently cast. (For example, cutting from long shot to medium shot, is that really her galloping into center stage of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in Annie Oakley, the only time she is seen on a horse in that film?) She insisted on doing her own stunts because she felt that it contributed to the consistency of characterization, as if she distrusted the wizardry of Hollywood effects.

As Nivel Busch noted about The Furies, doing her own stunts meant that Stanwyck jeopardized production schedules, as an injured lead actress can do great damage to a tight schedule. While there is little evidence of that happening, it is true that she endured many bruises with fortitude in order to respect shooting schedules, contributing to her great reputation as a consummate professional. She never fully recovered from the back injury of 1931 on the Laguna Beach and frequently wore a back brace, which accounts for her distinctive ramrod posture. Still, I wonder how often we are not watching Stanwyck at all but a double, whose injuries would not postpone a shoot.

Perhaps her most dramatic and emotional horse riding occurs in Blowing Wild, a film in which her character is something of an outsider in a male community of oil speculators. After being rejected by Jeff Dawson (Gary Cooper) yet again, Stanwyck as Marina Conway rides through the Mexican landscape across streams and under ancient bridges, pounding out her distress until she finally dismounts and collapses in tears on the ground.

Process shots are used for close-ups while she is riding and crying, and the animal is a valuable partner in the scene as her anger shifts to despair. In the same film, she races Jeff and her husband, Paco Conway (Anthony Quinn), with the two men driving in a 1940 Packard Custom Super Eight while she gallops through the countryside, beating them within seconds. The horse gives her a wild edge on the two men and, like many of Stanwyck’s riding scenes, creates a spectacle that briefly disrupts the narrative like a song-and-dance number, only with horses and scenery.

If women riding bicycles in Victorian times were considered transgressive, women straddling horses in mid-20th-century America were likewise titillating.

After 1940 the American Humane Society monitored studio productions in order to ensure animal safety. One thing that changed in the industry around the same time was the increased availability of horses trained to do stunts, some of whom became well known. For example, Stanwyck’s most famous stunt, being dragged by a horse through a tornado in Forty Guns, was accomplished with a horse named Oakie, ridden by a stuntman named Ken Lee. You don’t need to know a great deal about horseback riding to see that she has the wrong foot in the stirrup. Fuller took three takes before he got it right, gauging the best camera placement—not to authenticate Stanwyck’s riding technique but to capture the fear registering on her face.

In 1962 and 1973 Stanwyck was honored with awards for her riding, which were in recognition of her contribution to the art of western performance. One of the conventional mantras about women and horses is that they become sentimentally attached, as played out in films such as National Velvet (1944) and The Misfits (1961). Stanwyck, however, rarely plays this role and tends to treat her horses simply as transport out in the wilds. In The Moonlighter, for example, when her horse is shot and falls (hopefully it is a stunt horse), she simply grabs her rifle from the saddle and leaves the horse without a backward glance.

The ensuing shoot-out is one of her best action scenes, although the gendered conventions of the western genre were difficult to overcome. Ella Smith quotes a critic from the New York Herald Tribune describing this particular scene: “You might fidget a bit as Barbara Stanwyck, stylishly thin and looking mighty small beside a horse, fights it out with rifles with Ward Bond and wins. This, as anyone who has ever seen a Western knows, is practically impossible. Bond may lose a screen battle here and there but never to a wisp of a woman with rifles at 50 yards.”

In the climactic scene of The Moonlighter, Stanwyck’s character, Rela, who has been deputized as a sheriff, is walking her horse over a rocky ledge, leading Fred MacMurray to justice, when she slips and falls down a waterfall, slipping through rock crevices and bouncing to the river below. Stanwyck performed this stunt herself, apparently because the stuntwoman was not available that day or at that time. It’s a great scene, except that after MacMurray saves her, she forgives him for his crimes. The film ends with a repeat of the treacherous crossing, but this time MacMurray is in the lead, and they make it safely to the other side and romp away together into the hills.

The most spectacular stunts tend to involve the act of falling, so there is a kind of inner tension between Stanwyck’s affinity for dangerous riding and the tendency for her characters to fall off their horses, just to be saved by men. We know how often her power and independence are curtailed by the requisite happy endings of heterosexual romance, and the act of falling is often the price to be paid for riding high.

In The Maverick Queen she has a spectacular fall (probably performed by a stunt person) when Sundance (Scott Brady) “bulldogs” her off of her horse. They both roll down a cliff, but she stops just short of a precipice and sends down a log to knock the man off to the depths below. The film ends with her dying in her lover’s arms, a heroic death for a woman on the wrong side of the law.

As the New York Herald critic of The Moonlighter indicates, the appeal to male critics of Stanwyck on a horse in what were primarily B westerns, was her figure. The idealized western hero, male or female, is slim and trim, becoming an extension of the animal in silhouette, exuding the lightness of a jockey despite the heavy leather paraphernalia of saddle and guns.

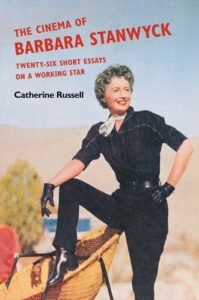

Stanwyck’s outfits are often commented on by critics, and she arguably helped make pants sexy on older women as a Parade magazine cover from 1955 indicated with her sporting black jeans, cowboy boots, and a black blouse. In 1935, for A Message to Garcia, she went on an all-celery diet to maintain a figure suitable to the riding breeches that she wears throughout the film. Nevertheless, in films such as All I Desire and The Lady Eve, Stanwyck rides sidesaddle—a Victorian style of riding that protects a lady’s chastity.

If women riding bicycles in Victorian times were considered transgressive, women straddling horses in mid-20th-century America were likewise titillating. To Stanwyck’s credit, she consistently rose above such gender nonsense with her posture and her strong characters. An exceptionally weak character, such as Cora in Trooper Hook, never rides horses but sticks to carriages.

_________________________

Excerpted from The Cinema of Barbara Stanwyck: Twenty-Six Short Essays on a Working Star by Catherine Russell. Copyright 2023 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

Catherine Russell

Catherine Russell is Distinguished University Research Professor of Cinema at Concordia University. Her books include Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices and Classical Japanese Cinema Revisited.