How Gerrymandering Helps Republicans Maintain Power in Texas and Georgia

Anjali Enjeti on the Systematic Dismantlement of Multiracial Voting Coalitions Across the Country

Galveston County, Texas, population 350,000, sits on the southeast end of the state along the Gulf of Mexico. The county, made up of 55 percent white, 25 percent Hispanic, and 13 percent non-Hispanic Black residents, is divided into four precincts. Residents elect a commissioner to represent each precinct. Until 2021, three of the four precincts, 1, 2, and 4, were majority white precincts. Fifty-eight percent of the population of Precinct 3 was either Black or Hispanic. The Black and Hispanic voters of Precinct 3 have a history of voting similarly on the issues, and since the 1980s, they have worked together to elect a commissioner to represent their interests.

The Commissioners Court itself is predominantly white and Republican. In 2021, the Honorable Stephen D. Holmes was the only Black commissioner and the only Democrat on the Court. Holmes had replaced the first Black County Commissioner ever, Wayne Johnson, after he passed away in 1999. Holmes was elected and re-elected by voters thereafter.

The more severely a district is gerrymandered, the more partisan a district becomes, and the less power a voter has in forging how their government is run.

In November 2021, eight years after the Supreme Court issued its decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which transformed the Voting Rights Act into a shadow of its former self, the white Republican members of the Galveston County Commissioners Court saw a golden opportunity to shake things up in Precinct 3. They divided its Black and Hispanic residents into the county’s other majority white precincts, reducing the total population of Black and Hispanic voters in Precinct 3 from 58 to 28 percent. Now all four precincts were majority white. Just like that, after decades of grassroots organizing, the multi-racial, Democratic communities in Precinct 3 lost their electoral influence on the Commissioners Court.

*

Every ten years following the census, the US Census Bureau establishes the number of House of Representatives seats in each state based on population numbers. This process is called apportionment. States with surging populations gain more House seats. States with declining populations lose House seats. Map drawers draft the outlines of these districts, as well as those for state senate and state house seats, city council districts, and county precincts, like in Galveston County. At a minimum, the map drawer must ensure that the population of the various districts is relatively equal.

In some states, map drawers attempt to draw districts in a way that preserves “communities of interest,” a somewhat nebulous and controversial concept where states lump people with similar socio-political and economic interests together. But for the majority of states, redistricting is a process involving political interests and manipulation known as gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering is named for Elbridge Gerry, a former governor of Massachusetts, who in 1812, signed a redistricting bill to keep his party, the Democratic-Republicans, in control of the state senate. Previously, the state senate districts had been drawn along county lines. The new map was like a jigsaw puzzle, with one district resembling a misshapen salamander. At a dinner party, so the story goes, a guest joked that it wasn’t a salamander, but a gerrymander. Though the Democratic-Republicans received an even larger number of seats after the next election, Elbridge Gerry was not re-elected to governor.

In most states, the state legislature, or more specifically, the majority political party in the state legislature, has the power to draw the maps. How the maps are drawn determines how much weight a ballot carries in an election. The more severely a district is gerrymandered, the more partisan a district becomes, and the less power a voter has in forging how their government is run.

In other words, gerrymandering is a potent method for political parties to gain or maintain control. The Republican Party has had majority control in the majority of state legislatures since the mid-1990s. Thus, the GOP has been able to draw quite a few maps based on their political agenda. Following the 2020 census, state Republicans drew maps for 177 districts for the House of Representatives, or 41 percent of the body. Democrats drew only forty-nine or 11 percent of the districts. Courts, independent commissions, and political commissions drew the remaining districts.

Partisan map-drawers have the ability to create as many safe seats for their party as possible. The safer the seats, the less likely their candidates will face a competitive opponent the next election cycle. Partisan gerrymandering has resulted in far fewer competitive seats over the years. This was especially true of the House of Representatives races in 2022, which according to FairVote, had “a particularly high number of uncontested seats and a particularly low number of competitive seats.” A lower number of uncontested or noncompetitive seats can depress voter turnout. Why would voters turn up to the polls if they’re certain their vote won’t affect the election outcome?

Partisan gerrymandering, according to the 2019 Supreme Court decision, Rucho v. Common Cause, falls outside the purview of federal courts. Racial gerrymandering, which violates section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, is within the purview of the courts. The distinction may seem straightforward, but the waters between partisan and racial gerrymandering are muddied. This is because racial and ethnic groups tend to congregate in the same geographic region, and voting trends tend to correlate with race and ethnicity.

One of the biggest threats to illegal racial gerrymandering is the swiftly changing racial and ethnic demographics in the US. Social scientists have predicted that by the year 2044, non-Hispanic whites will be in the minority. In theory, this should make it more cumbersome for political parties to distort districts based on race in order to influence election outcomes. Unfortunately, federal courts always have the last word.

*

The DOJ knew it had an uphill battle in Petteway v. Galveston County. In its complaint it relied, in part, on a 1998 Fifth Circuit case, Campos v. City of Baytown, Texas, which found that Black and Mexican American voters constituted a viable voting block for a claim under the VRA. The US District Court judge followed the decision in Campos and instructed Galveston County to redraw its map, in a major victory for the voters of Precinct 3.

But in August 2024, the same Fifth Circuit Court overturned the district court by discounting the decision in Campos, its very own precedent. Judge Edith J. Jones, writing for the majority, concluded: “After reconsidering Campos en banc, this court holds that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not authorize separately protected minority groups to aggregate their populations for purposes of a vote dilution claim.” The court further opined that if the Supreme Court had intended to allow for different races to form a single class of plaintiffs it would have stated so in Thornburg.

The judge’s reliance on Thornburg over Campos is out of touch with modern day reality. Despite the undeniable persistence of segregation across the US, many geographic areas are becoming more racially diverse. Multiracial voting coalitions, like in Galveston County’s Precinct 3, are far more common today than they were when Thornburg was decided decades earlier. Based on the Fifth Circuit Court’s bizarre logic, racially diverse minority communities are essentially exempt from the protections of Section 2 of the VRA.

*

In late 2024, unsurprisingly, Commissioner Holmes lost the election for the precinct he’d held for over twenty-five years to Hank Dugie, Galveston County’s white Republican treasurer. The race wasn’t even close. Dugie won Precinct 3 with 68 percent of the vote, proving that the new map did exactly what it was intended to do. Every commissioner serving on the Commissioners Court was now Republican.

This wasn’t the only blow to the Democratic voters of Precinct 3. The County figured out another way to defend itself against the claim of racial gerrymandering. In 2022, a judge appointed Republican Dr. Robin Armstrong, who is Black, to temporarily fill the seat of Precinct 4, one of the predominantly white precincts. Armstrong ran unopposed later that year to serve a full term for the precinct. Predictably, Galveston County now argues that Armstrong’s presence on the Commissioners Court proves that the county map was drawn based on politics, not race. As such, the County has filed motions for the federal judge to dismiss Petteway v. Galveston.

The case is still tied up in federal court. But it’s not likely that the Black and Hispanic voters of Precinct 3 will ever see a fair map.

*

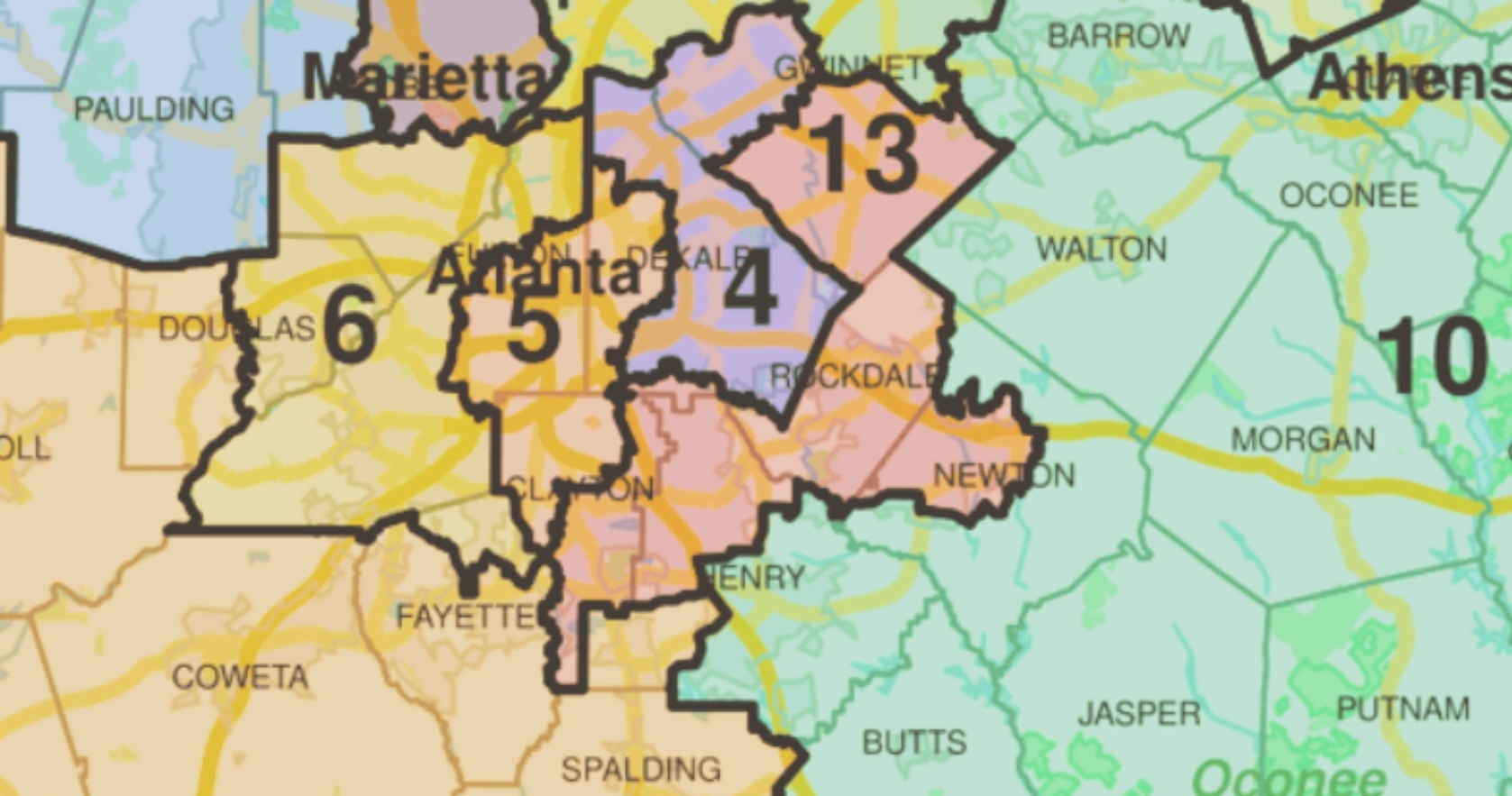

In my northern Atlanta suburb, I’ve experienced a dizzying degree of gerrymandering in a short period of time. In 2017, my home sat just inside Georgia’s sixth congressional district (CD-6). This district included the very northern parts of two Democratically leaning counties, DeKalb and Fulton. It also included enough of the Republican-leaning part of Cobb County to keep the entire district Republican.

The sixth congressional district has served as a launching pad for Republicans with ambitions to advance through the ranks of their party. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich held the seat for twenty years, from 1979 to 1999. Former Senator Johnny Isakson took over from Gingrich and served until 2005. Republican Tom Price was elected after Isakson decided to run for Senate.

In the spring and summer of 2017, however, a few months after Donald Trump’s first inauguration, a series of special elections sparked a movement to elect more Democrats to the then Republican-majority 115th Congress. When Trump tapped Congressman Tom Price to serve as Secretary of Health and Human Services, a special election was scheduled to fill the vacant seat in CD-6. Several Democratic candidates filed to run. One of them was Jon Ossoff, a millennial who had once interned for Congressman John Lewis. That spring Ossoff handily won the Democratic primary and then faced a formidable challenger from the Republican Party, former Georgia Secretary of State Karen Handel.

Ossoff’s campaign received national media attention. At the time, it was deemed the most expensive House race in history. It also inspired a large-scale mobilization of Democratic voters in a congressional district that the party had largely ignored in previous cycles. Ossoff’s popularity among voters made a district flip a real possibility.

In the years since the 2010 census, CD-6’s demographic had shifted considerably. A critical number of Black and Latino voters had moved into the district, and the Asian Pacific Islander population boomed. The 2010 map, and the way Republicans had drawn it to protect their party’s longevity, failed to reflect the burgeoning racial diversity of the region.

CD-6 was up for grabs.

A multiracial and multiethnic block of voters stomped hard for Ossoff. Despite this, Handel beat him by just under four points. Those of us who volunteered for his campaign felt discouraged, yet hopeful. The race had been close. For the first time, the future of CD-6 looked blue.

With a single stroke of a pen, our Democratic communities were sucked back into a ruby red stronghold.

Ossoff declined to run for the seat again in 2018, but Lucy McBath, a national spokesperson for the anti-gun violence organization Moms Demand Action, whose seventeen-year- old son Jordan Davis was shot and killed in 2012, decided to run against incumbent Handel. McBath won. This victory helped deliver a Democratic House majority in 2019. In 2020, McBath won re-election with an even wider margin over Handel.

The sixth congressional district wasn’t the only district that had dramatically changed since Georgia’s 2010 census. My state senate and house seats had been held by Republicans for years. Due to the post-2010 demographic evolution in the area, they, too, flipped blue in 2018.

Imagine for one moment what this was like for me, a lifelong Democratic voter who’d spent two-thirds of my voting life in some of the reddest regions of the South. My House Representative, my state senator, and my state representative were Republicans in 2018. In 2019, I lived in three Democratic districts.

Of course, it was too good to last. The 2020 Census was upon us.

The redistricting following the 2020 Census switched me from CD-6 to Georgia’s seventh congressional district (CD-7), a solidly Democratic one, which primarily encompassed Gwinnett County, one of the most racially diverse counties in the US. My former district, CD-6, had been redrawn to a solidly Republican one. McBath knew she couldn’t win it, so she jumped ship from CD-6 to run in CD-7 against incumbent Democratic Congresswoman Carolyn Bourdeaux. McBath bested Bourdeaux in the primary and easily won the general election that November. She remained my House Representative.

In the meantime, voting rights groups sued Georgia over the new 2020 maps, arguing that they violated the Voting Rights Act by placing large numbers of Black voters into too few districts, just like the Alabama plaintiffs argued in Allen v. Milligan. Even with an eroded VRA, the case was a strong one. Georgia’s Black population makes up 30 percent of the state. The Peach State has one of the largest Black populations in the US. An additional majority Black district was warranted.

A federal district judge agreed and required the state to redraw the maps. The new map positioned CD-6 further west, into a far more multiracial and Democratic region of the state.

In the reshuffle, though, CD-7, my safe Democratic congressional district, had also been redrawn. It still included politically mixed North Fulton County, where I live, but now also captured two counties, Lumpkin and Dawson, with 94 percent white populations. The seventh congressional district had been drawn so far north, and so far out of the metro Atlanta area, its northwest corner sat only ten miles from the Southern Terminus of the Appalachian Trail. In one fell swoop, the revised map transformed my very racially diverse and solidly Democratic district to a very white and solidly Republican one. I’m now represented by Republican Congressman Richard McCormick.

Georgia’s post-2020 map redrawing also resulted in two additional Black-majority state senate districts. Unfortunately, my own formerly overwhelmingly Democratic state senate district, like CD-7, now also encompassed the state’s northern, whiter counties. Which meant I had been ripped away from a heavily Asian district, where I had been represented by Democrat Dr. Michelle Au, the first Asian Pacific Islander elected to the state senate, and dumped into a Republican-leaning one, now represented by Republican Shawn Still, who had traveled to Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021, to help overturn the presidential election outcome. (Au ran for, and currently represents my state house district.) Though Still been indicted on seven counts, including criminal racketeering and other felonies, unbelievably, Governor Brian Kemp is allowing Still to continue to represent my district.

My former congressional district had been home to a large community of Black, Asian, and Latino voters. The new maps, which gave more representation to Black voters elsewhere in Georgia, disenfranchised the majority-minority multiracial coalition in the north and northeast suburbs of Atlanta. If we abandon the Fifth Circuit Court’s nonsensical decision in Petteway v. Galveston, and instead apply the logic in Campos v. City of Baytown, Texas, we can conclude that the revised CD-7 map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The plaintiffs in Coakley Pendergrass v. Raffensperger agreed and filed a complaint requesting a re-draw of the boundaries of CD-7. But the judge refused to recognize the multiracial block in the case before him and upheld the revised map.

Like in Galveston County’s Precinct 3, the results of years of organizing in our primarily Black, Latino, and Asian congressional district vanished into thin air. With a single stroke of a pen, our Democratic communities were sucked back into a ruby red stronghold.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Ballot by Anjali Enjeti. Copyright © Anjali Enjeti, 2026. Published in Bloomsbury Academic’s Object Lessons series.

Anjali Enjeti

Anjali Enjeti is a former attorney, journalist, activist, and election worker based near Atlanta. She is the author of two award-winning books, Southbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social Change, and the novel, The Parted Earth. Her other writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, Harper’s Bazaar, Oxford American, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing in the MFA programs at Antioch University in Los Angeles and Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia.