How Gay Activists in 1980s NYC Rallied Police to Their Side

On the Creation of the Anti-Violence Project

The Anti-Violence Project was, at heart, a reaction to systemic apathy to queer life, and it began on the cusp of the AIDS epidemic.

In March 1980, three men in Chelsea were attacked by white kids wielding bats. One man lost two teeth; another sustained 36 stitches to his forehead, a damaged eye, and a broken nose. This did not make the local papers. Assaults of gay men were commonplace, and this one, at first, was no different. For months, men had driven in from New Jersey, Long Island, and the outer boroughs of New York City to throw bottles at Village and Chelsea residents who were presumed to be queer. Sometimes attackers would get out of the car, chase them down, and beat them. Reporting such violence to the police was considered not worth the trouble, for there rarely was any recourse. As an activist told the Daily News that December, “If you go to court and it’s brought out that you’re gay, the defense will make a bum out of you.”

It is, therefore, difficult to accurately quantify the anti-queer violence in New York City during those years. In 1980, the NYPD claimed not to collect such figures. Daily News columnist Pete Hamill, writing the year before about protests of the movie Cruising, succinctly described the situation:

Such violence has been common for a long time now; much of it does not get reported to the newspapers, or even to police (because many homosexuals remain firmly in the closet). Some of this violence is merely part of the texture of city life, a risk faced by all citizens. But some of it is clearly directed at homosexuals.

Official statistics aside, however, there’s an evident trajectory. Between 1985 and 1989, the number of anti-queer incidents reported by local groups increased from 2,042 to 7,031. These figures are almost certainly on the low side. As for the nature of anti-queer violence: a paper, published at the beginning of the decade, argued that murders of gay men were characterized by an uncontrollable anger, present in nearly every case. “A striking feature of most murders,” wrote the authors, “is their gruesome, often vicious nature.

Eventually, circumstances required radicalization. In Chelsea, law and order seemed not to exist, as exemplified by the beatings.

“Seldom is a homosexual victim simply shot,” they continued. “He is more apt to be stabbed a dozen or more times, mutilated, and strangled. In a number of instances, the victim was stabbed or mutilated even after being fatally shot.”

The March 1980 incident is remembered, and would be repeatedly cited, only because of the fallout. The victims were escorted to the neighborhood’s Tenth Precinct, accompanied by members of the Chelsea Gay Association. Formed in 1977, CGA was conceived not strictly as an activist organization but as a means for new, queer residents of Chelsea to meet each other and build a community. In practice, its membership was limited to hundreds of gay men and a few bisexual women.

Eventually, circumstances required radicalization. In Chelsea, law and order seemed not to exist, as exemplified by the beatings. CGA representatives demanded the Tenth Precinct place additional patrols on the streets, particularly before summer, when violence would surely increase. The precinct commanding officer refused, on the grounds that there was no need. In other words: You’re on your own.

Six weeks later, sponsored by more than a dozen community groups, CGA held an emergency forum on the second floor of the Church of the Holy Apostles’ parish house. “YOUR NEIGHBORS ARE ORGANIZING TO FIND SOLUTIONS TO VIOLENCE AND CRIME IN CHELSEA,” read a flyer.

Among the attendees were city council members and neighborhood activists, including Thomas Duane, who would soon be elected state senator but was, for the time being, selling advertising for the New York Native. Precisely what was said during the forum was never recorded, but the gathering had its desired effect—it demonstrated the considerable strength of the attendees, who represented a burgeoning political constituency. As recounted in Arthur Kahn’s The Many Faces of Gay, within days or weeks, activists secured meetings with the offices of the Manhattan district attorney, the chief of police, and the City Housing Authority. Within months, a spinoff of CGA was formed: the Chelsea Gay Association Anti-Violence Project.

The spinoff began in the apartment of Russell Nutter and Jay Watkins, who were described by a friend as “devoted to each other; a couple in every sense of the word.” Within weeks, they were receiving tips from a hotline about anti-queer attacks, providing informal counseling, and helping victims grapple with the Victim Services Agency and other bureaucracies. “As time went on,” a CGA board member wrote years later, “several of the volunteers learned quite a bit about the ins and outs of the various state and city organizations, and some became quite well known to police, district attorneys, and agency staff.”

As news of the hotline spread, calls came in from throughout the city with reports of all manner of violence. It was a painful success. To meet the growing need, Nutter and Watkins scaled up, amassing a crew of forty volunteers to work out of a room subleased from a gay-owned real estate company. The pair continued to coordinate the volunteers, raise funds, and monitor the hotline. It was exhausting, and Nutter and Watkins were noticeably drained.

In September 1982, the Native reported the hotline was overtaxed and needed fresh volunteers. There were recent reports of entrapment by police patrolling the Jacob Riis Park bathhouse. Nutter estimated that 1,200 arrests had been made that summer alone. Hotline volunteers must be willing to talk to survivors for several hours a week, wrote the Native, and “[e]ssential characteristics for volunteers would include patience, understanding . . .”

That year, with the help of Duane, AVP received a grant of $6,000 from the New York State Crime Victim Compensation Board. A press release announced a new name and expanded ambitions: the New York City Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project. In its short life, the release noted, the organization had documented cases of anti-queer violence in all five boroughs, dispatched volunteers to accompany victims of violence to the police, and worked with district attorneys’ offices in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens. Volunteers soon received reports of more than a dozen anti-queer crimes a week.

With its new funding and independence, AVP needed an inaugural executive director and found one in Rebecca Porper, a recent graduate of Manhattan’s Union Theological Seminary. She was brought in to fundraise, make a name for the organization, shine a light on anti-queer crime, and act as a liaison with governmental entities—including the district attorney’s office, the police, and the mayor’s office—to whom, according to Porper, most of AVP’s board was hostile: “They didn’t know how to go about it except to scream at them.”

Outreach to the police began at the precinct level, and had been one of CGA’s initiatives since the beginning. Back then, when such sessions were called “sensitivity trainings,” Lance Bradley, known primarily as a self-defense instructor, provided guidance to cops about anti-queer violence. AVP would eventually expand those services to neighborhoods in less affluent queer communities, such as Jackson Heights, Queens, and Park Slope, Brooklyn. But the initial focus was on so-called gay ghettos: Chelsea’s Tenth Precinct and the West Village’s Sixth Precinct.

Following the morning roll call, Bradley led discussions about crimes committed against his community. He told the officers why the city’s queer citizens were afraid of them and what they could do to alleviate such fears. Trainings were not welcomed; Bradley and his successors were often ridiculed. Once, during a discussion of anti-queer violence, an officer sitting in the front row produced a pair of women’s panties and began fingering them.

Decades later, when Porper reflected on her own training sessions, her view of their efficacy was measured. The chasm between the police and AVP was unbridgeable, she felt, and success was on the margins: “They didn’t want to know from gay guys, at that time. They weren’t so afraid of AIDS, but they really didn’t like gay people. So my strategy was to simply say, Look, guys. You come into my city. I pay you very generously. I give you training. I give you a uniform to wear. I give you health benefits that are the most extraordinary health benefits in the United States. In exchange for that, what I want you to do is take every thought you have about gays and throw them out, and treat the gay men and the lesbians that you meet as people. When you take off the uniform and go back to wherever you live, you can do whatever you want. But when you’re in New York City: no. Then they relaxed, kind of, because I wasn’t challenging their preconceptions.”

For years, the cops referred to Greenwich Village’s Sixth Precinct as Fort Bruce. “It was a tongue-in-cheek reference to the gay community, in the fact that Bruce had gay connotations to it,” says a retired policeman. More serious, and dehumanizing, was the police’s insistence on calling AIDS “the gay disease” and donning gloves when handling anyone suspected of being afflicted. This reflected a fear of AIDS, but also a department-wide unease with queer New Yorkers.

The Tenth Precinct in Chelsea, which covered the west side of Manhattan between Fourteenth and Forty-third Streets, was equally problematic. General corruption was an issue, of course, with many of its officers accused of taking payoffs from bars, clubs, and brothels. Where queer-related crime was concerned, the Tenth’s response tended to be, What did you do to deserve this? The officers deployed a tactic from domestic disputes: mediation. As the Native reported, as an alternative to an arrest, a victim of an anti-queer crime who desired prosecution had to “serve a summons on his or her attacker to report to an Institute for Mediation and Conflict Resolution Dispute Center.”

As perhaps the only queer organization with a positive working relationship with the NYPD, the Anti-Violence Project served as an intermediary between the two parties.

Despite such indignities, AVP calculated it was more productive to create a partnership with the Sixth and the Tenth precincts and appeal to their sense of decency, rather than act as a thorn in their side. We’re New Yorkers who need your services, they told police. We are being victimized because of who we are.

In July 1985, ostensibly as an attempt to improve community relations, Mayor Edward Koch’s office founded the Police Council on Lesbian and Gay Concerns, headed by Chief Robert Johnston. A big Irishman, Johnston was considered tolerant, to a point. He said all the right things and seemed personally empathetic, but he allowed his officers to arrest seventeen members of ACT UP during its first protest—of pharmaceutical company profiteering—in front of Wall Street’s Trinity Church. What ACT UP wanted was to protest long enough for media outlets to snap photos before police either dispersed the crowds or arrested those who refused to leave. As perhaps the only queer organization with a positive working relationship with the NYPD, the Anti-Violence Project served as an intermediary between the two parties. Johnston was asked if, from now on, the police would give the protesters more time. Sometimes they did.

The council, whose members included AVP, the transit cops, the DA’s office, and Koch’s gay and lesbian liaison, met every six weeks at NYPD headquarters, Manhattan’s One Police Plaza. Individual cases weren’t discussed, but Johnston brought in commanders to talk about precinct-level trainings, the AIDS crisis, and bias crime. In practice, it was as much for the benefit of the police as it was for the civilians, because it was in Johnston’s interest to placate the queer community—particularly if he wanted to stay in Koch’s good graces. As a colleague put it, “The last thing he wants is for people to call up the Mayor’s office and say to Ed Koch, ‘Hey, you know that guy, Johnston? He’s a real pain in the neck.’ ”

Koch’s representative was among a number of liaisons positioned as conduits between the city and the queer community. The district attorney’s office had its counterpart, which grew out of Morgenthau’s reelection campaign. The young woman, Jacqueline Schafer, was tasked with outreach to such organizations as Gay Men’s Health Crisis and AVP, training ADAs on how to improve treatment of gay victims, communication on issues related to law enforcement, and, at least in the early days, accompanying victims to precincts to report crimes. Schafer was hired by Linda Fairstein, an assistant district attorney now chiefly remembered for supervising the prosecution of five Black teenagers, known as the Central Park Five, for a rape they did not commit. She had run the sex crime unit for a decade. “There had been so many times when witnesses had come to the criminal justice system, and had not been met fairly,” Fairstein recalled. From the DA’s perspective, the liaison was a chance to say to the queer community, You’re going to be well met here. You’re going to be listened to.

A less charitable view of the councils and liaisons holds that they were, by design, incapable of serving the needs of the constituents. While queer New Yorkers believed liaisons existed to represent them to the mayor’s office or the district attorney, observed an activist, “The truth is, in fact, exactly the opposite. These liaisons exist to represent the Mayor’s office, the DA, and whomever else, to the community, and to essentially be apologists for those offices. Their job is to suppress community dissent, placate the community when the community is making demands of the powers that be.”

During Porper’s tenure, Morgenthau’s office asked AVP to work with his attorneys on anti-queer violence prosecutions. Such crime presented a challenge because the judicial system was only beginning to take these cases seriously. This was, in essence, a new kind of crime and required a new strategy for effective prosecution.

The prevailing defense in those years was “gay panic”—a defense against charges of murder and assault that enabled perpetrators of anti-queer murders to receive diminished sentences or even avoid punishment entirely by, in effect, blaming the victim. This defense had been common-place for decades, going back to at least the 1960s. It tended to come in one of three variants of defense theory: provocation, in which the defendant argued that discovery of the victim’s sexual orientation was sufficient to drive him to murder; self-defense, in which the defendant claimed that the discovery of the victim’s homosexuality caused him to reasonably believe he was in grievous and immediate physical danger; and, finally, diminished capacity or insanity, in which the defendant argued that being made aware of the victim’s sexual orientation induced a short-term mental collapse or mental breakdown, which spurred the killing.

A few months before he died at the age of ninety-nine, Morgenthau pungently described the gay panic defense as “that bullshit excuse.”

__________________________________

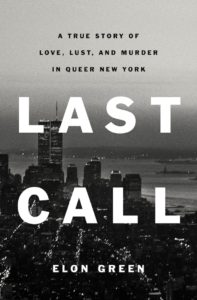

From Last Call by Elon Green. Copyright (c) 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of Celadon Books, a division of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC.

Elon Green

Elon Green has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker, and appears in Unspeakable Acts, Sarah Weinman’s anthology of true crime. Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York was his first book and won the Edgar Award for Best Fact Crime. Green was an executive producer on the HBO series adapted from Last Call.