How Flight Embodies Our Deepest Yearning

Richard Farrell on Writing, Yearning, Flying, and Falling

I was ten years old when I fell in love with flying. I remember the day, the hour, the very airplane—an AV-8A Harrier. Stuck in a fifth-grade science classroom, perpetually bored and staring out windows, I was not expecting a jet to zoom low and fast over the autumnal tree line. The year was 1979, and the first-ever Worcester air show had begun. For the next four days, this extravaganza of flight would transform the skies above my hometown. The heavens filled with more aircraft than a boy could imagine: vintage biplanes, World War II bombers, massive gray cargo jets, tankers, helicopters, and fighter planes with mythical names like Skyhawk and Corsair, Phantom and Super Saber.

Hour after hour, I’d whiplash my neck staring into the clouds, listening for the bassy whir of turbo props at breakfast, the thunder of afterburners at dinner. The sun scorched my face; my eyes ached from strain. With the roar of each engine, I’d burst from my house as if it were on fire to gaze at the next airplane. How did people continue with their routines? There were no pilots in my life. The neighbors were teachers and nurses, shop foremen and letter carriers. My father, an avowed white-knuckler, occasionally traveled for business but hated flying; I’d never seen my mother board an airplane. Until that air show, the world of aviation was as foreign to me as a Moroccan bazaar. And yet, for one glorious fall weekend, the skies above me became dramatically alive. My soul was utterly hijacked—a conversion every bit as profound as a prophet’s, an annunciation so fundamental that my life changed forever. I devoted the next ten years to becoming a pilot.

I wrote The Falling Woman, in part, to channel this love of flying that once burned in me. That same passion informs the character of Charlie Radford, a boy who grew up much like I did. Our adult lives suffered similar fates as well. Like Radford, I became a pilot but my flying career was cut short by a medical condition, and like Radford, at 23, I was told that I could no longer be a professional pilot. It took a decade for me to recover from that loss; Radford’s recovery is, I think, well underway by the time the novel ends.

After my flying career, for a brief time I too worked in an aviation-related job in Washington, DC, though not as an accident investigator. I came to see how the mythology and heroic imagination that I had once associated with flying quickly fizzled behind mounds of paperwork, bureaucracy, and regulations. The real tragedy was how completely the adult world sacrificed passion for the sake of mundane work. I wanted to keep Radford’s joy alive, to sustain his idealism, to help him rediscover his wings.

At some point early in the writing, the chaos of trying to complete the novel began to overwhelm me. A hundred thousand words, three years of work, and I still didn’t know what I was trying to say. I began to see that the work of an NTSB accident investigator and the work of a novelist share more than a few common traits. Fear, uncertainty, the balance of order and chaos, the puzzle-piecing construction of meaning—these are the central ingredients for the storyteller, as well as the accident investigator.

But then there is the falling.

I didn’t set out to write a novel about an impossible story of survival. I wanted to write a quiet book, but on page one I blow up an airplane and send a passenger hurtling through the roof of a Kansas barn. Spoiler alert: she survives. Such a thing has really happened, at least five times from my research. There’s no easy explanation for how. In World War II, three fliers fell (without parachutes) from exploding airplanes and survived. In the 1970s, a Serbian flight attendant, Vesna Vulović, was sucked out of an airliner, fell from six miles up, and lived. And then there is the story of Juliane Koepcke, a German teenager who fell out of a disintegrating plane from 10,000 feet, landed in a rainforest canopy, and crawled out of the jungle ten days later.

Barely over a hundred years old, powered flight is the very embodiment of one of humankind’s deepest yearnings.

What fascinated me about these miraculous stories was how little the survivors talked about their incredible luck. Koepcke did eventually write a memoir, but she spent less than a page on her actual freefall. It was as if these miraculous falls could not be addressed, as if the stories were too unbelievable to be told.

And yet, as I wrote various drafts of this novel, solving the mystery of Erin’s freefall became less important to me. I was drawn to aspects of her character not because of her freefall, but because she’d spent two decades yoked to a traditional life—a restless wife, a working mother, a privileged suburbanite who voted and tended to her gardens. What does her everyday life mean outside the shadow of this miracle? Spared against all odds, does she have an obligation to live her life differently? Do any of us? Contemplating these questions eventually helped me solve the mystery of the novel itself.

The French writer Simone Weil once wrote: “Utter permanence and extreme fragility give an equal sense of eternity.” The Falling Woman wrestles with extreme manifestations of this paradoxical truth. Barely over a hundred years old, powered flight is the very embodiment of one of humankind’s deepest yearnings. But we take the awe for granted, forget how miraculous the everyday world truly is. In the end, though, no matter how high or fast we fly, we are ultimately falling—falling toward each other, toward despair and hope, toward love and loss, and, with a little luck, falling toward a deeper understanding of ourselves.

__________________________________

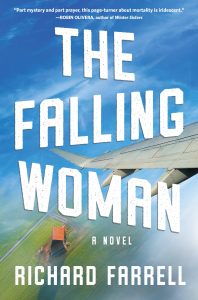

The Falling Woman by Richard Farrell is available now from Algonquin Books.

Richard Farrell

Richard Farrell is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and a former pilot who holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Hunger Mountain, upstreet, New Plains Review, Potomac Review, Descant, and elsewhere. Originally from Worcester, Massachusetts, he teaches creative writing at Grossmont College in San Diego, where he lives with his wife and two children. The Falling Woman is his debut novel.