How Fiction Allows Us to Inhabit Animal Consciousness

Kathleen Rooney on Some of Her Favorite Non-Human Narrators

For centuries, human thinking—at least in the West—has been dominated by the notion, said to have originated with Aristotle, of the Scala Naturae, or the Ladder of Life. Also known as the Great Chain of Being, this concept establishes a hierarchy in which all life forms can be arranged in ascending degrees of perfection with humans, conveniently, at the topmost rung. Even after Darwin came along and replaced this model with his considerably less vertical Tree of Life, the idea of the human mind as the apex of biological consciousness has persisted.

Increasingly, in the face of climate catastrophe, more humans are beginning to question their hubris. In the introduction to their 2017 book Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, the editors note: “Some scientists argue that the rate of biological extinction is now several hundred times beyond its historical levels. We might lose a majority of all species by the end of the 21st century.” This, the arguable point of no return, affords a chance to examine the received belief in human exceptionalism. Science writing in particular and nonfiction in general have much to say regarding the similarities between human and non-human minds, but fiction offers opportunities to explore this interconnectedness as well. After all, if fiction has the power to show us another individual’s private and interior uniqueness, then why not depict animals possessing such interiority?

In his remarkable essay “Why Look at Animals?” from his 1980 book About Looking, John Berger writes that, “To suppose that animals first entered the human imagination as meat or leather or horn is to project a 19th-century attitude backwards across the millennia. Animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises.” Books with animal narrators—not just books about animals, but books that situate the reader deeply and consistently inside an animal’s point of view—are relatively rare. The books below send messages and promises to their readers that, far from standing outside of so-called “nature,” humans are animals too.

*

Jack London, White Fang

(Puffin Books)

Globally, dogs are the most popular pet, said to be owned by approximately 33 percent of the world’s population. So it’s no surprise that canine points of view are well represented in literature. In 1906, Jack London published White Fang, the vivid and at times shockingly violent story of a wolfdog born and raised in the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush of the 1890s. Like any fascinating human protagonist, White Fang and his life story are exceptional. As London writes in the close third person, at first “White Fang knew nothing of the heaven a man’s hand might contain for him” and “Besides, he did not like the hands of the man-animals,” but London’s story follows the arc of the wolfdog’s journey from feral wildness to domestication, as White Fang eventually ends up with a loving owner in California, illuminating the changeability and potential for heroism in humans and animals alike.

Virginia Woolf, Flush: A Biography

(Harvest Books)

Flush: A Biography, Virginia Woolf’s 1933 contribution to canine literature, focuses on the Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel. Woolf’s decision to inhabit Flush’s perspective allows her to deliver an enchanting look at what it might have been like to be a beloved pet in the mid-1800s, as well as to reveal the life story of Browning and her husband Robert from a heretofore unseen angle. The scene of Elizabeth and Flush’s first encounter is as charming as any rom-com meet cute:

Each was surprised. […] There was a likeness between them. As they gazed at each other each felt: Here am I—and then each felt: But how different! Hers was the pale worn face of an invalid, cut off from air, light, freedom. His was the warm ruddy face of a young animal; instinct with health and energy. Broken asunder, yet made in the same mould, could it be that each completed what was dormant in the other? She might have been—all that; and he—But no. Between them lay the widest gulf that can separate one being from another. She spoke. He was dumb. She was woman; he was dog. Thus closely united, thus immensely divided, they gazed at each other. Then with one bound Flush sprang on to the sofa and laid himself where he was to lie for ever after—on the rug at Miss Barrett’s feet.

John Berger, King: A Street Story

(Vintage)

In his 1999 novel, King: A Street Story, the aforementioned John Berger gives a 24-hour account of life in the streets from the first-person perspective of King, the guardian and protector of a homeless couple living in squalor but with dignity in a desolate encampment near a highway in France. King listens with a compassionate dignity of his own to the dialogue spoken by his human compatriots, allowing Berger to paint a moving portrait of the dispossessed in a society that is much more shamefully dog-eat-dog than its actual dogs tend to be. King’s observations of his surroundings are both sensorily engulfing—as when he notes, “The nights are still cold enough to make a body shiver if it’s not well covered, but no longer cold enough to kill”—and intellectually provocative, as when he says, “The hatred which the strong feel for the weak as soon as the weak get too close is particularly human; it doesn’t happen with animals. With humans there is distance which must be respected, and when it isn’t, it is the strong, not the weak, who feel affronted, and from the affront comes hatred.”

Richard Adams, Watership Down

(Scribner)

Watership Down, Richard Adams’ rabbit epic, sold over a million copies in the UK alone in the first two years after its 1972 publication, maybe because its blend of the familiar (bunnies) and the strange (one of the bunnies has ESP!) is so compelling. By using a third-person omniscient point of view that has primary access to the hero rabbit Hazel’s thoughts and feelings, Adams creates a sweeping saga that has inspired critics to notice its similarities to the Odyssey and the Aeneid. Often classified as kids’ literature, Watership Down blends fantasy and extensive research—he credited the book The Private Life of the Rabbit by naturalist Ronald Lockley as being instrumental to his understanding of wild bunny behaviors—to create an unsettling adventure story that examines the inevitable gaps between idealism and reality within virtually any community, no matter how well-intentioned.

Andrzej Zaniewski, Rat

(Arcade Publishing)

Translated from the Polish, Andrzej Zaniewski’s brief, bleak novel 1990 novel Rat gives the reader 176 brutal pages of how it might feel to be the title animal from birth to death, a savage and grim existence in which “Time passes imperceptibly, like the black streams of sewage and refuse.” Although Zaniewski clearly esteems the world of rodents, his meditation on these much-maligned creatures eking out their survival in the shadows of human civilization is not a pleasant read, and it’s not supposed to be. A poet, a teacher, and a journalist, Zaniewski argues in his author’s introduction that “We have long stopped seeing partners in animals. We view them only as biological elements that should be subordinated to our will, our knowledge, and our whims. We judge the animal’s intelligence insofar as it submits to us.” But, he warns, both in this intro and in the book as a whole, “don’t think that you love and fail, win and lose, or live and die differently from a rat.”

Verlyn Klinkenborg, Timothy; Or Notes of an Abject Reptile

(Vintage)

In 1789, early English ecologist and curate Gilbert White published The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne in which he made frequent reference to a tortoise he inherited from one of his aunts. In 2006, Verlyn Klinkenborg published Timothy; Or Notes of an Abject Reptile, his novel based on the 13 years during which the titular reptile resided in White’s garden. Sagacious and full of gentle judgment, Timothy—actually a female—was kidnapped from her original Mediterranean environs and now spends her days perplexed and bewildered by “the great soft tottering beasts” who consider her and other animals their property. Of her owner’s attitudes in his Sunday sermons, Timothy remarks: “Humans believe that the parish of Earth exists solely for their use. Fabric of cottages, roofs, sheds and shops. Shelter of brew-houses, malt-houses, ash-houses, granaries, kilns. […] Walks and alleys and side yards of this village. The comfort of the human establishment. Chambers and hearths as welcoming as the human face.” Klinkenborg lets the reader see what Timothy sees when she stares unsparingly back.

Tania James, The Tusk That Did the Damage

(Vintage)

Set in South India, Tania James’ 2015 novel The Tusk That Did the Damage isn’t told entirely from an animal point of view, but her move of including the perspective of a bull elephant known as Gravedigger adds complexity and heartbreak to her examination of the ivory trade. Weaving the exploited and long-suffering Gravedigger’s voice in with those of a young poacher and an American documentary filmmaker lets James depict interspecies conflicts and power imbalances with nuance and freshness. In the book’s first chapter, Gravedigger, as a calf, witnesses his mother’s murder as she tries to protect the herd from a human attack: “The man in the tree was pointing a long-snouted gun. Another blast—the tusker bellowed, deep and doomed. The Gravedigger whirled in search of his mother, and when at last he caught her scent, he found her roaring in the face of the gunman who aimed into her mouth and shot.” Motivated by revenge and self-preservation, Gravedigger comes to trample humans to death, then covers them with dirt (hence the name) before returning to the forest where he lives in hiding. Through her use of the close third person, James makes Gravedigger as morally multifaceted a character as any of the humans who surround him.

Deb Olin Unferth, Barn 8

(Graywolf Press)

A comic and unapologetically political indictment of factory farming, Deb Olin Unferth’s 2020 novel Barn 8 also rotates among various points of view, among them those of the hens at the heart of the heist being plotted by the book’s activists. The two main human characters—Janey and Cleveland, industry egg auditors—plan to liberate almost one million chickens from an atrocious egg farm. In an interview, Unferth explained that “I always wanted a sort of Cubist portrait of what was happening. I wanted many points of view, perspectives, voices, all looking at and talking about this one event: all the hens leaving that farm.” The almost overwhelming, cacophonous heterogeneity of the narration—including a particularly winsome chicken called Bwwaauk—results in a book that achieves Unferth’s aim of causing the reader to expand their taxonomies of personhood: who and what we are willing to grant subjectivity and why.

__________________________________

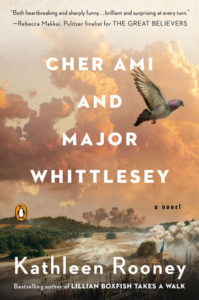

Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey by Kathleen Rooney is available now from Penguin Books.

Kathleen Rooney

A founding editor of Rose Metal Press and a founding member of Poems While You Wait, Kathleen Rooney is the author, most recently, of the novel Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey, based on the true story of a pigeon and a soldier during World War I, out this month from Penguin. Her previous work includes poetry, fiction, and nonfiction and has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Allure, Salon, The Chicago Tribune, The Nation and elsewhere. She teaches English and creative writing at DePaul University and lives in Chicago