How Feminists Fought to Formally Recognize Women’s Domestic Labor

From Emily Callaci's Cundill Prize-Shortlisted “Wages for Housework”

For most of my life, I did not think very much about housework. A middle-class teenager in the “Girl Power” 1990s, I learned that my liberation would come through education, creative expression, and professional success. Thanks to the efforts of feminists who came before me, I never felt I had to rebel all that hard against the expectation of feminized domesticity. I intended to spend my time on earth on more meaningful things: love, politics, music, beauty. What did housework have to do with me? It seemed like a quaint preoccupation—the relic of an older generation’s outdated and irrational beliefs about gender. That women were associated with housework seemed a category mistake: correct that mistake, and you fix the problem.

But then, when I became a mother, housework became inescapable. I experienced the housework of motherhood differently than my mother, who quit her job as a social worker to raise me and my brothers until my youngest brother was old enough for school. I remember her at the dinner table in the evenings with the three of us while my father was out, doing what I imagined as very romantic work as a union organizer. In stories about my father’s childhood, I picture his mother, my brilliant grandmother, who left a job as a journalist when her first child was born, tending lovingly and skillfully to five children, often while my grandfather wrote poetry in his attic study. (She returned to journalism when she was in her sixties, after her children were grown.) When their children were school-aged, both my mother and grandmother became public school teachers, choosing careers that adapted to the rhythms of their children’s lives. These images of my mother and grandmother invoke in me feelings of warmth, safety, and love. Still, I never expected to play a role similar to them. It seemed unproblematic to me to identify with the men and their work: I’d emulate the union organizer, the poet.

Housework is, therefore, not unproductive or external to the economy. It is the most essential part of the capitalist system.

I have not had to fight all that hard against an expectation that, as a woman, I should do a disproportionate amount of housework, yet housework is nevertheless a struggle that I share with my partner. In at least one way, our household is typical for our generation of Americans: both adults in our house work full-time outside the home for money, and the work of maintaining our family gets squeezed into the time that is left after we’ve satisfied the demands of our employers. We live in a country that, over the past few decades, has collectively experienced declining real wages, shrinking social services, and rising costs of education and healthcare. We negotiate housework between us (as I write these words, he is at home with our two boys while I sit alone in my friend’s empty house to write free from distraction), but we also distribute it beyond us. To be able to work, we rely on paid childcare; to pay for childcare, we need to work; and this entire cycle relies on the fact that the extremely skilled women who care for our children are paid less money for their work than we are for ours. There is no way around it: I am a beneficiary of an exploitative social arrangement. By participating, I also feel that I am undermining myself: I consent to a world in which the work of caring for children—the work that, for the past few years, I have spent most of my time on—is valued less than the work of being a professor.

Housework weighed most heavily on me when I returned to my full-time job as a history professor, four months after my first son was born. If housework is work—and it certainly was work in the physical meaning of the word—then together with my paid job, I was working eighteen-hour days. These were clearly poor working conditions. I know from growing up in a union family that one of the most effective ways to contest poor working conditions is by going on strike. But the feminism I grew up with had put me in a bind: if feminism was the right to pursue success and equality in the workplace, then to refuse my salaried job was to refuse the very thing that I had learned was the source of my liberation, autonomy, and sense of accomplishment. To refuse the work of caring for my child would be to harm the most vulnerable of beings, and the person I loved most in the world. Parenting young children during the pandemic only deepened my growing sense of a loss of power: that motherhood, the work that I knew I could never refuse, made me vulnerable to exploitation.

I was drawn to Wages for Housework because I wanted to understand what had changed in my life, and to make sense of my mixed feelings about it. Put another way, I wanted to understand how motherhood had changed my relationship to capitalism. And I wanted alternatives. I turned to feminist writings from the 1970s, wondering how the diverse, ambitious, imaginative, revolutionary ideas of that generation had gotten narrowed into the version of feminism that had been offered to me as a young woman. One of the places I looked for insight was in Silvia Federici’s 1975 manifesto “Wages Against Housework,” a rousing and elegant call to confront housework head-on as a site of women’s systemic oppression, rather than imagining that, as individuals, we can find a way out of it.

Around that time, I learned that Silvia Federici was assembling her archive at Brown University, located in the town where I grew up and where my parents still live. So, on a long visit during my maternity leave, I left my son and several bottles of extracted breastmilk with my mother while I went (breastmilk pump in tow) to explore Federici’s collection of writings, manifestos, and gorgeous black-and-white photographs of women marching in the streets of New York and London and Rome. One flyer from the New York Committee seemed to address me directly. In it, they demanded support for the work of mothering in the form of collectivized daycare, subsidized by the government, not in order to free mothers up to work harder at our jobs, but to free us up for…whatever the hell we want. A nap. Art. A swim in the ocean. Slow, luxurious sex. Time to nurture our friendships. Time to participate meaningfully in politics. Having grown up with a feminism that equated liberation with the right to pursue success at work, this was a revelation: a feminism that was unabashedly anti-work.

Silvia Federici’s archives led me to other feminist thinkers in the Wages for Housework campaign: Mariarosa Dalla Costa, the student militant who started the Italian Salario al Lavoro Domestico campaign in the wake of Italy’s wave of wildcat strikes and student uprisings; Selma James, wife and comrade of the Trinidadian Marxist C. L. R. James, who launched a Wages for Housework campaign out of their apartment in London; Wilmette Brown, a poet and former Black Panther who, together with the Barbadian community organizer Margaret Prescod, launched Black Women for Wages for Housework in Brooklyn and Queens.

I started from questions about my own life, but Wages for Housework took me far beyond it. Housework is everywhere, once you start looking for it.

Feminists launched the Wages for Housework campaign in 1972. But the word “campaign” doesn’t quite capture it. Wages for Housework is perhaps best understood as a political perspective, which starts from the premise that capitalism extracts wealth not only from workers, but also from the unpaid work of creating and sustaining workers. An employer who hires an employee gets more than what they pay for: they get the labor of the person who shows up to work, and they get the labor of a second person who is at home sustaining him (for in the early writings of the campaign, the waged worker was presumed to be a “him”). That second person feeds the worker, makes his home livable, does his laundry, does the shopping, nurtures his body and soul, raises his children. It is all this hidden labor that makes it possible for him to come to work all day producing profit for his boss. Housework is, therefore, not unproductive or external to the economy. It is the most essential part of the capitalist system because it produces and maintains the most important source of value: the worker. Yet those who perform this work are not entitled to a share of the wealth they create. To the contrary, they are often among the most impoverished and dependent members of society.

Wages for Housework reframes women’s poverty as systemic impoverishment: women are not unfortunate victims in need of charity, rather, they are exploited workers in need of justice.

The systemic exploitation of women’s unpaid work is hidden by a powerful myth: that women are naturally suited to housework. For a woman, keeping house and caring for family fulfills her natural desires, and should be reward enough. Compensation would sully the virtuous nature of this work, for the home is imagined as a refuge from the impure, punishing world of work and market relations. Capitalism relies on this myth to keep women in these roles, allowing others to profit from their work. Wages for Housework was so jarring to people because it demanded compensation for something that was supposed to be free from market forces, and which women were supposed to provide out of love. Campaign members saw this as a form of emotional blackmail. As one of my favorite Wages for Housework slogans sums it up: They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.

By demanding payment for work that women had historically done for free, members of the Wages for Housework campaign made visible their role in capitalism. They aimed to destroy what they saw as a false distinction between work done in the marketplace for wages and unpaid housework done in the home and community. In so doing, they aimed to call into being a truer, more expansive, inclusive working class to dismantle capitalism and all its forms of oppression.

Wages for Housework is a critique not only of women’s oppression, but of global capitalism in its entirety. It argues that, because women do housework for free, work that resembles housework is undervalued: the more similar a job is to housework, the lower its status and the less it is paid. Moreover, when governments cut social services, such as childcare, education, healthcare, elder care, and disability services, they exploit the fact that women will step in and provide these services without pay. The analysis can be applied at a global scale. The scholar-activist Andaiye, who launched a Wages for Housework campaign in her home country of Guyana in the early 2000s, applied the perspective to structural adjustment policies: the austerity measures imposed by the IMF and World Bank on countries in the global south as a condition for foreign aid and bank loans. With stunning clarity, she writes: “Structural adjustment…assumes correctly that what women will do in the face of the deterioration that it brings is to increase the unpaid work that we do without even thinking about it in an attempt to ensure that our families survive.” Wages for Housework puts austerity politics in a new light: what politicians call fiscal conservatism or “belt-tightening,” Wages for Housework reframes as freeloading on the unpaid work of women…

…Wages for Housework was controversial when it was proposed in the 1970s. Few feminists disagreed with the insight that housework was essential, and hidden, and that it would be politically powerful to recognize it. But many were uncomfortable about the money part. Some argued that it would invite capitalism into their homes, bringing even more areas of life into the wage relation and commodification. Others chafed at the suggestion that, having struggled so hard to escape housework as their destiny, women should then identify with housework by demanding payment for it. The most common critique was that wages for housework would institutionalize women as housewives, doubling down on the link between women and housework, rather than destroying it. Many struggled to understand: how does getting paid for housework allow you to refuse that work? If you are demanding to get paid, aren’t you then agreeing to do that work?

In the history of the campaign, I have encountered ambiguity on this point. Some have stated that the money was never the goal, but rather a provocation that aimed to change consciousness and catalyze social transformation. By contrast, others in the campaign have insisted that the money is the most important thing: Wages for Housework is not an intellectual exercise, they insist, but a fight to get money into women’s hands. What members of the campaign all agree on is that the wage was never the end goal but rather the first step in a much larger struggle for power. This is why the word “wage” was so important. When Margaret Prescod, founder of Black Women for Wages for Housework, used her platform at the historic 1977 US National Women’s Conference to insist that welfare be called a wage rather than a benefit, more than semantics was at stake. To recognize that welfare is payment for the work of mothering, rather than poverty alleviation, changes the entire political relationship. Wages for Housework reframes women’s poverty as systemic impoverishment: women are not unfortunate victims in need of charity, rather, they are exploited workers in need of justice.

__________________________________

From Wages for Housework: The Story of a Movement, an Idea, a Promise by Emily Callaci. Copyright © 2025. Available from Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books UK. Wages For Housework has been shortlisted for the Cundill History Prize.

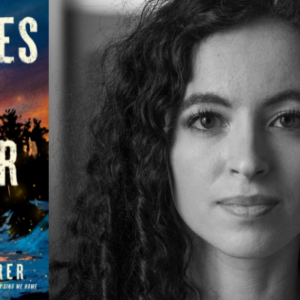

Emily Callaci

Emily Callaci is a historian and writer, currently Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Wages for Housework is her first trade book.