How Eudora Welty's Photography Captured My Grandmother's History

Natasha Trethewey on Experiencing a Past Not Our Own

I was given my first copy of Eudora Welty’s Photographs in 1990, not long after the book’s initial publication. Back then I was in my first year of graduate school, having committed myself to becoming a writer. Of course, I had found my way to Welty before that—through her stories and her illuminating meditation on the origins of her work in One Writer’s Beginnings. As a native Mississippian, I was drawn to this remarkable woman as much for the clarity and vision and truth of her fiction as for the history we shared—rooted in place—the fate of our geography.

“Place,” she wrote, “geography and climate shapes characters. . . . It furnishes the economic background [a writer] grows up in, and the folkways and the stories that come down to him in his family. It is the fountainhead of [her] knowledge and experience.” Looking at her photographs, I found the documentary evidence: the truth not only of her imagination but also of her experience, her deep observation, a record of what she had seen.

This was transformative for me. Already, I had begun writing notes in my journal for poems about my maternal grandmother, a black woman born in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1916, who’d come of age in the 1930s. As long as I can remember I had been listening to the stories about her life, her journeys, the work she’d done to survive, the work she loved, her faith and endless striving. I listened trying to see the palimpsest of her world overlaid on my own, the Mississippi I’d entered in 1966, 50 years after her, on the heels of major advancements in the civil rights movement—the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and ’65.

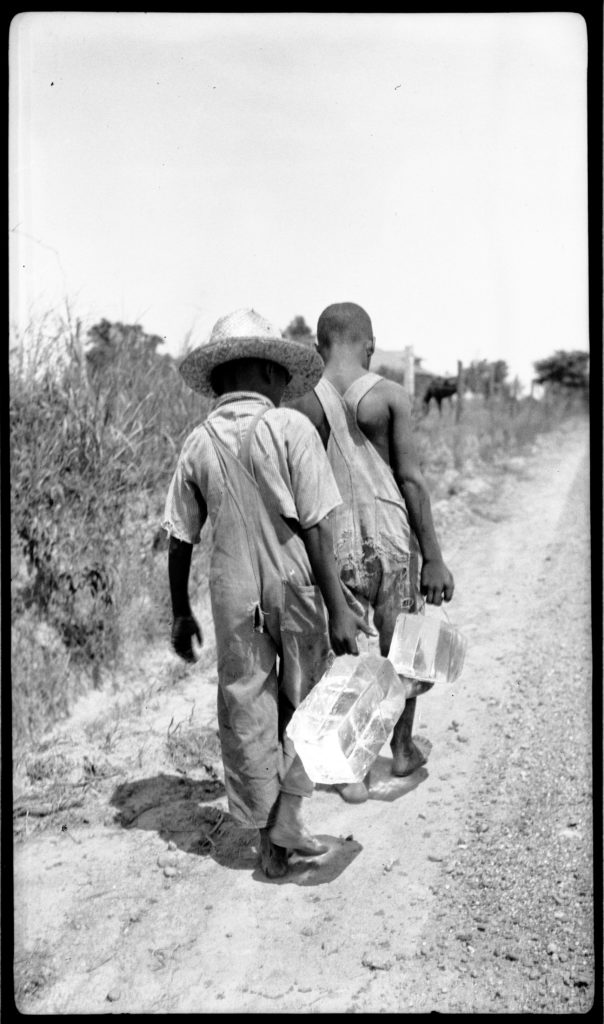

Though things were changing, the remnants of the Jim Crow world my grandmother had grown up in, the world Welty had photographed, were everywhere around us. “Poverty in Mississippi, white and black,” Welty said, “really didn’t have too much to do with the Depression. It was ongoing. Mississippi was long since poor, long devastated. I took the pictures of our poverty because that was reality, and I was recording it.”

Photographs of the place where I was growing up would have shown many of the same material conditions as in Welty’s photographs of black Mississippians in the 1930s. My North Gulfport was impoverished and still partially rural, but it was also a place of resilience and joy. I woke most mornings to the crowing of a rooster, hymns in my grandmother’s resonant alto, her laughter as she chatted in the yard with Uncle Mun—a man, deaf from birth, who spoke only in percussive syllables, choked and guttural. Beneath our house, an expanded shotgun propped two feet off the ground on cinderblocks, I could hear pigs rooting in the dirt. There were chickens and hogs, often loosed and roaming; a skinny cow behind a fence in our neighbor’s yard; fig, pecan, and persimmon trees; a church across the street where I learned recitations for the various pageants put on throughout the year; shotgun shacks and unpaved roads.

My own experience of the place had provided a glimpse into what had become a rapidly vanishing past, but the Mississippi I was trying to document—to see, my grandmother’s—was far in the distance, blurred and impressionistic. A young writer, I was like a nearsighted watchman, absent my corrective lenses, straining the limits of my vision.

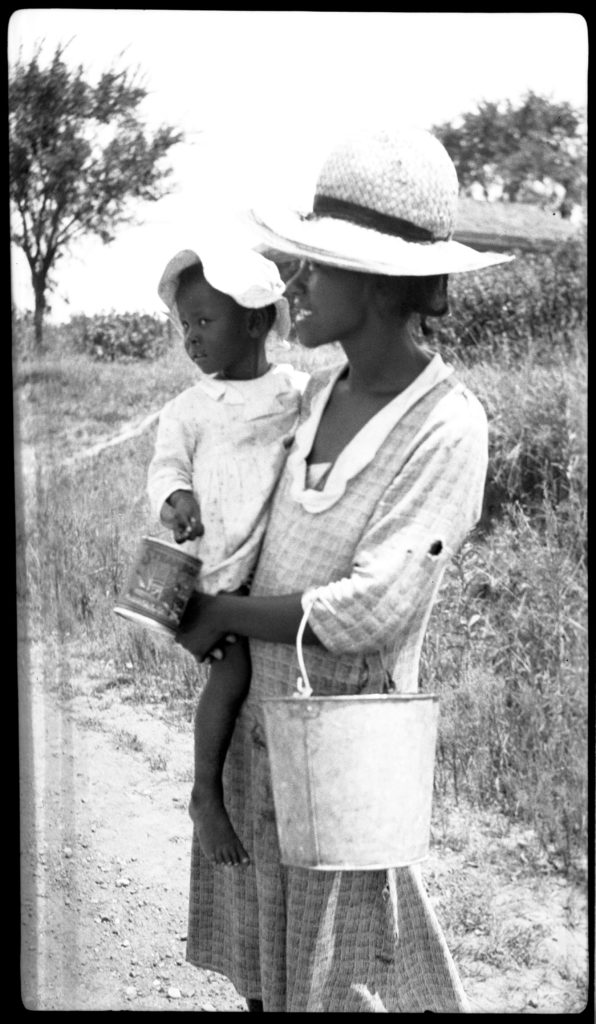

Though in my mind’s eye I could imagine the nearly vanished world from my grandmother’s stories, I had not been there, had not seen: the street scenes, the candid expressions and subtle interactions, the intimacies and ordinariness, the details on a dress or apron (my grandmother had proudly described floral-print clothing sewn from cotton cornmeal sacks). Nor had I realized, amidst the constant barrage of cultural images diminishing or rendering monolithic a people—my people, southern, black, of a particular time and place—that there was evidence of another way of seeing: a vision rooted in an unvarnished attempt to show reality. Eudora Welty’s photographs provided that other way of seeing, the visual, historical evidence: “a record,” she has said. “The life in those times.”

That record was the lens I needed.

*

One of Welty’s photographs from Jackson in the 1930s shows a young woman in a street scene, poised on a curb as if about to step off and cross the street. She seems on the verge of something, paused in her forward motion as if to present herself as a woman with places to go. Her hair is perfectly waved beneath her proper hat, and she stands as if she were posing for a fashion drawing—the envelope of a Vogue or Butterick pattern—to display a smart day coat. There is a clutch bag under her arm, her elbow crooked so that her hand, clad in a black leather glove, rests lightly in her coat pocket—a picture of elegant nonchalance, though the look on her face suggests something else. What? Wariness? Awareness—of self or otherwise?

It’s hard to know, but Welty captures the ambiguity, the woman’s inner complexity. When I first saw the photograph, I couldn’t help but think the woman seemed powerfully in charge—an equal participant in the reality that the photograph captures. In it, I see a manifestation of my young grandmother, the decades younger version of the person I’d come to know—a well-dressed woman who’d made all of her own clothes, and then my mother’s, with the patterns she bought in downtown Gulfport or New Orleans.

The grandmother I grew up with—older, the wisdom of her age etched lightly on her smooth face—might have been the woman in Welty’s photograph of Ida M’Toy. Standing on her porch, the woman raises her chin, the hint of an enigmatic smile teasing the corners of her mouth. When Welty photographed her, the former midwife was self-employed, operating a secondhand clothing store in her home.

All my life, my grandmother had been self-employed, too, making draperies in the front workroom of her house, and she displayed that same quiet pride I see on the face of Ida M’Toy. Everywhere we went she kept her chin tilted up, a gesture I’d come to understand as the posture of dignity in spite of and resistance to a lifetime of Jim Crow. Welty captures that dynamic, as well as the subtleties of class—from bootlegger to nurse—that might otherwise go unnoticed by viewers for whom that time and place are unfamiliar. Her gaze is both monumental and intimate, never that of the interloper.

Welty’s photographs were, for me, a resource, a way to see a time and place I’d only encountered in history books and my grandmother’s stories. I began writing poems with those images in mind, each one a starting place to anchor visually what I’d heard in the cadences of my grandmother’s voice, how she’d say—reaching the end of a story—That’s just the way it was.

Throughout this remarkable collection, Welty shows us again and again the way it was. I’m reminded of this each time I return to the haunting image of the ruins of the antebellum mansion at Windsor Plantation. The ornate columns that remain stand as monument to the past, the history of slavery, the wealth amassed by cotton planters in Mississippi. Welty captured that, but she captures something else as well.

Perhaps most compelling is her actual presence in the photograph, a literal manifestation of the lasting imprint of her vision: her shadow on the ground in front of the ruins, the Rolleiflex camera in her hands. You might imagine her a ghost of history, hands clasped before her as if to pray. You might see how the shape of her dress, the position of her arms gives the appearance of an angel, an intermediary showing us her guardianship and reverence not for the nostalgia of the past, but the truth of it.

__________________________________

Photographs © Eudora Welty, reprinted by permission of Eudora Welty LLC; courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. New foreword copyright © 2019 by Natasha Trethewey.

Natasha Trethewey

Natasha Trethewey is an American poet who was appointed United States Poet Laureate in 2012 and again in 2014. She won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for her 2006 collection Native Guard, and she is a former Poet Laureate of Mississippi. She is the Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University.