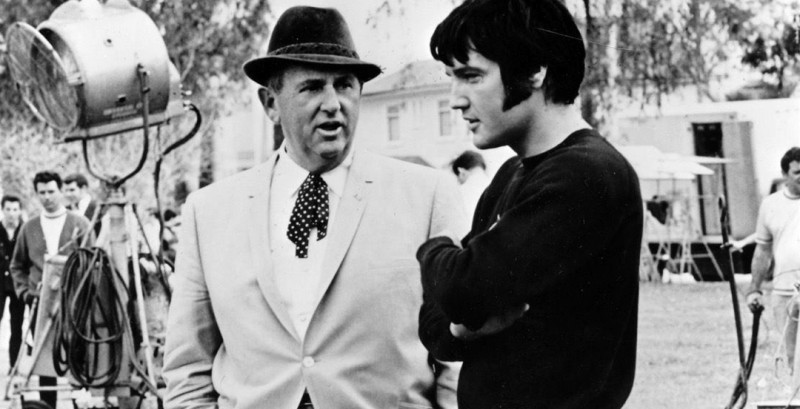

How Elvis Presley and Colonel Tom Parker Made Music History Together

Greg McDonald and Marshall Terrill on the Fraught Yet Successful Partnership of Two Industry Titans

In late February 1972, President Richard Nixon made a historic trip to China in an effort to ease long-term tensions and hostilities after years of diplomatic isolation. Not only did this visit strengthen Chinese-American relations, but it also served to encourage progress with the USSR.

I was driving Colonel Parker from Los Angeles to Palm Springs as we listened to a radio broadcast of this event, live via satellite from China. The Colonel’s mind went into overdrive as he learned about this new technology, which would allow people to hear and see someone around the world on radio and television. He blurted the first thing that came to his mind.

“What a great way for people everywhere to see and hear Elvis!” he said.

He knew a show by satellite could make entertainment history and Elvis was the perfect worldwide star to pull it off.

But how do you achieve something that has never been done before? I have been around lots of wealthy and influential people. Many of them come up with great ideas such as these, but 99.9 percent of them never get off the drawing board. If they do, there is a team of people doing the nuts and bolts to pull it off. Colonel Parker was a one-man show. He was among that .01 percent who worked tirelessly to realize his vision. This idea, he felt, could be very big… but it would need some more thought.

The Colonel insisted that no other artist ever ride on Elvis’s coattails.

The world was changing, and so was Elvis. Elvis and Priscilla were separated and talk of a divorce was making headlines everywhere. He had been living under the age-old male belief that the husband could play around, but the wife was to stay home and remain faithful and raise their child. Despite Elvis’s infidelities, Priscilla had remained faithful for years. She’d finally had enough and told Elvis she was leaving him. He did not take it well, but he was about to meet the wonderful Linda Thompson, who was his main girlfriend for the next four years. Linda and I are friends to this day. Linda’s brother, Sam, had worked as a sheriff’s deputy before he became Elvis’s bodyguard in July 1976. Sam was a trusted friend of Elvis’s, and the two men spent hours singing gospel songs together on tour.

After Elvis’s passing, Sam attended law school and became a very successful lawyer and judge. Later he became a member of the Nevada Transmission Authority and the Public Utilities Commission. Sam was also a warden of a prison for a spell, which is ironic because he’s the sweetest guy in the world. He and his wife, Louise, are close friends of mine, and we stay in touch and travel together to Elvis-related events. After his legal career, Sam started a record label with music impresario David Foster, which they later sold to Warner Music. Linda and Sam were two of the few people in Elvis’s inner circle who did not do drugs and tried to help Elvis with his addiction. Sam believes, despite all of Elvis’s success, deep down he remained humble if not a bit insecure.

“Elvis used to sit up nights and wonder why he had become the King and someone else had not—someone like Jerry Lee. He really did ponder on this issue cosmically: ‘Why me?’” Sam said. “He knew he was talented, and he was good looking, and at the right place at the right time. But there were a lot of others out there too. He truly felt humbled by that. He never truly came to grips with it.”

The relationship between Colonel Parker and Management III Productions was growing strained. The Colonel was aware that Weintraub was using his power with the Elvis tour to promote his own artist, John Denver. The Colonel insisted that no other artist ever ride on Elvis’s coattails, and Jerry was really pushing the boundaries. The Colonel often spotted Weintraub stepping outside the offices and conducting business that had nothing to do with Elvis. Weintraub also invited other artists he was trying to sign to Elvis’s concerts to show off his relationship with the star.

In the world of show business, what Weintraub was doing was an accepted practice, but that did not fly with the Colonel. He was growing more agitated with the situation and Weintraub’s swelling ego.

When on tour, Jerry was often on the phone handling his personal affairs and not taking care of business. When their private jet was ready to leave, they’d have to wait while someone ran to get Jerry off the airport phone. The Colonel was also getting reports that Jerry was difficult. The Colonel waited until the tour was over to make his move.

The contract for Elvis’s winter tour in November was signed on September 12, listing only three names: Elvis, the Colonel, and RCA Records. Management III Productions was not going to be involved.

With his load lightened, the Colonel was free to think. And he was thinking a lot about turning the satellite idea into reality. He contacted NBC president Tom Sarnoff about selling the show to countries all over the world, and Sarnoff got it done. The eventual tally was thirty-eight countries plus the British protectorate of Hong Kong. The special was not broadcast in Russia, China, Africa, South America, the Middle East, or South Asia.

Parker and Sarnoff set a tentative concert date for November 18 at the end of Presley’s winter tour, but it was scrapped at the request of MGM president Jim Aubrey. Wisely, he wanted to avoid the special overlapping with the theatrical release of Elvis On Tour, which was scheduled for November 1. He wanted to protect the $1.6 million investment his studio made, which won the award for Best Documentary Film at the 30th Golden Globe Awards the following year. The Colonel agreed to push the special back a few months.

A date was finally set for the satellite show on January 14, 1973; a charity was announced (the Kui Lee Cancer Fund), and a name was given to the special: Aloha from Hawaii.

The special also came with a hefty paycheck: Elvis was paid $900,000 (equivalent to $6 million in 2022) from NBC for a one-hour concert.

Before the historic concert was announced in September 1972, at a press conference in Las Vegas, Colonel Parker issued an announcement that outlined several of what he called historic “firsts” for the broadcast:

This would be the first live concert to be broadcast in its entirety worldwide via satellite.

This would be the largest audience ever to witness a concert, with expectations “in excess of one billion people.”

This would be the first time in the history of the record industry that an album would be released worldwide simultaneously.

Elvis made an appearance at the press conference with RCA president Rocco Laginestra, who flew in for the event.

“What are we going to say, Colonel?” he asked.

“Rocco, you’ll think of something when the time comes,” the Colonel replied.

The afternoon conference took place on the Hilton’s thirtieth floor inside the Crown Room, which boasted a panoramic view of the entire western Las Vegas valley. The small stage featured a floor-to-ceiling display of fifty of Elvis’s Summer Festival straw hats, each with the name of a major foreign country. The media attending the event had no idea what it all meant but would soon find out.

Elvis, sporting a white high-collared suit, aviator sunglasses, and longer-than-usual hair, sat next to Laginestra with the Colonel off to the side. Rocco announced, using RCA’s recently unveiled GlobCom satellite and accompanying technology, that Elvis would appear live in Honolulu, Hawaii, and would be seen in virtually every major country in the world either live or on tape delay. Laginestra caused quite a stir when he announced to the attending media this special event would draw more than a billion people from around the planet, instantly making it one of the biggest entertainment events of the twentieth century.

Colonel Parker had scored another first and was giving the world an opportunity to see the world’s number one superstar without ever having to leave American soil. Elvis was sweaty and looked distracted.

“How do you pace yourself, so you’re up when you need to be up?” a reporter asked.

“I exercise every day, and I vocalize every day,” Elvis replied. He may have been slightly exaggerating on that first part. He was tipping the scales at a hefty 195 pounds at that point, which didn’t go unnoticed.

NBC named Marty Pasetta as the special’s producer-director. He had produced broadcasts of the Oscars, Emmys, and Grammys. He had also helmed The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, The Andy Williams Show and Don Ho’s five TV specials, which were highly popular in their day and also filmed on location in Hawaii.

Presley loved his ideas and, in one of the few instances in his career, he overruled Colonel Parker.

Pasetta did his homework and attended Elvis’s Long Beach concert on November 15. He walked away from the show disappointed, feeling Elvis’s performance was flat and uninspired.

“He stood there like a lump,” Pasetta remembered. “He didn’t do anything. I went back to NBC and said, ‘Hey, guys, what am I going to do with this guy? How long is the show? Ninety minutes? I can’t tap dance that much. It doesn’t look like he’s going to move.’ They said, ‘That’s your problem.’”

When Pasetta finally met Elvis at Graceland, with his armed bodyguards hovering close by, they spoke for nearly four hours. He spoke about his vision for the show, which included an eighty-foot runway six feet off the ground so Elvis could walk down the center of the audience and have women coo at him. But that presented a problem, not with Elvis, but with the Colonel, Pasetta recalled.

“The Colonel always had the stage ten feet above the floor, and he had guards across the front. He didn’t want to have anybody touch his boy,” Pasetta said. “When I told this to the Colonel, he had a fit. He said, ‘I’m not lowering the stage. I’m going to have my guards there, and he can stand there and sing.’ I said, ‘That’s not going to work on the tube for an hour and a half show.’ He said, ‘No. I won’t do it. You can’t do the show.’”

But Pasetta said Presley loved his ideas and, in one of the few instances in his career, he overruled Colonel Parker.

“Elvis said to me, ‘The Colonel controls my business. I control my creativity and my music and my show. He has nothing to say about it. That’s your rule. You will deal with Joe Esposito,’ who was sort of a go-between,” Pasetta said. “I talked to Joe, the Colonel…everybody. But I tried not to deal too much with the Colonel. I had enough problems getting the show on.”

One of the last things Pasetta told Elvis in their marathon meeting was that he needed to drop about twenty pounds. Pasetta said the room went eerily quiet.

“He [Elvis] sat straight, and the guys on either side of him took out their guns and laid them down on the table,” said Pasetta. “And if you don’t think I was scared, you’re crazy.”

Pasetta needed Elvis skinny because he was going to film him up close, from his neck to the top of his head. He said he was shooting close because it would capture Elvis’s true sex appeal for the camera. All well and good, but he still didn’t know how Elvis would react to his bluntness.

“He jumped out his chair. He grabbed me, put his arms around me and said, ‘You’re the first person who was ever honest to me,’” Pasetta said.

But the goal was easier said than done. A decade earlier—no sweat. But now Elvis was thirty-eight years old, and his metabolism had obviously slowed. But he gave Pasetta his word and Elvis planned to keep it.

Elvis immediately went on a strict diet where he drank lots of protein drinks and boiled minuscule portions of protein and vegetables in hot water. He also went on long daily jogs and extended karate workouts. The diet also included daily injections of protein taken from the urine of a pregnant woman to burn up fat in the system. He wasn’t allowed to use anything with fat in it, including lotions, shaving creams, and shampoos.

To Elvis’s credit, he stuck with the regimen and lost the weight, about twenty-five pounds in all. He looked great, and he arrived in Hawaii a few days before the concert in fighting shape. All he had to do now was get a tan, not a problem in the Aloha State.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Elvis and the Colonel: An Insider’s Look at the Most Legendary Partnership in Show Business by Greg McDonald and Marshall Terrill. Copyright © 2023. Available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Greg McDonald and Marshall Terrill

Greg McDonald is an entertainment producer who got his start in show business with Colonel Tom Parker, who knew him when he was a teenager. He managed Ricky Nelson for seventeen years, ran Sonny Bono’s mayoral and congressional campaigns, and was president of Transcontinental Records (Backstreet Boys, NSYNC and O’Town). He’s also produced several feature films, television series (Making the Band) and large-scale concerts. McDonald manages Colonel Tom Parker’s show business assets, including his name, likeness and image. He resides in the Palm Springs area with his wife Sherry. Marshall Terrill is a music, film, and sports writer and the author of numerous books, including biographies of Steve McQueen, Elvis Presley, and Pete Maravich.