How Edna Lewis Exemplified the Ethos of Queerness Throughout Her Life

John Birdsall on the Unconventional, Trailblazing Existence of an Icon of Southern Cooking

I claim no knowledge of Edna Lewis’s romantic leanings, no insight into her desires. I cannot name the people she shared a bed with or compile a list of those she lusted after or loved. Edna’s intimacies are outside the scope of What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution. What concerns me is unraveling queer to mean something more comprehensive than romantic or physical longing. My focus here, as I trace the rise of a culture of food that challenges power, is the queerness of the outsider.

Seeing Edna through a prism of queerness—it takes us closer to bell hooks’s notion of queerness as something bigger and more inclusive than the clapping of flesh and the rustling of sheets. hooks renders herself “queer-pas-gay”: queer in opposition to gay, a state of disidentification with coercive homosexual orthodoxy. She distills queerness this way: As “the self… at odds with everything around it,” the self that has to “invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

Queerness is a reach for authenticity; the work of cutting through coercive norms—even those cemented by gay power—to descend to truer and truer places. Queerness is a life of inner ferment, the endlessly repeated birth of the self into a world that despises difference and would starve it, and it’s the quest for shelter, for sustenance. Queerness is making peace with estrangement, a digging in and making do where the alternative—the smothering imperatives of the dominant world—is what makes making do feel like joy.

Café Nicholson was for a brief moment this inclusive, ego-driven, transformative, way-too-much, colossally queer experiment in creative expression.

Within the encoded gayness of Café Nicholson, with its insinuations of bohemian, Edna finds ground to root her outsider talent. She’s a woman with no restaurant training or experience, suddenly cooking at a high level in the spare idiom of true luxury. She shops in Italian markets downtown, sources bread from an Italian baker, makes do with the available tools—limited, janky—to manifest elegance. And she’s persuasive: the idiom Edna will apply at Café Nicholson lives after her time there; goes on to help define a queer language of food that flows beyond the lines and edges of that particular restaurant.

It’s a language I first took in at Miss Ollie’s, a restaurant chef Sarah Kirnon launched in Oakland, California, in 2012. Not long after opening, Kirnon hung a John T. Hill photo portrait of Edna above the pass, next to one of her grandmother, Miss Ollie—a tribute, Kirnon tells me, to Edna’s work and dedication; to the delicacy of her flavors; her touch. To me, out in Kirnon’s dining room, it signaled Edna’s status as mother, muse, and conscience in a restaurant where queerness roamed like an animating spirit. With the image of Kirnon and her cooks through the pass, under a sort of photographic retablo of Edna and her candescent smile, I started to see how some queer essence of food and hospitality could be another piece of Edna’s legacy.

Later in life Edna’s close to Scott Peacock, a white man nearly fifty years her junior, a chef originally from Alabama. He is at various times her working partner, domestic support, roommate, and collaborator on the 2003 book, The Gift of Southern Cooking.

When they met, in 1988, Scott was a chef at the Georgia governor’s mansion, just twenty-five years old, keen on living and cooking in Italy. He was struggling with his sexuality. “It was something I fought with for such a long time,” Scott says.

After Edna died, Scott revealed how she gave him support to come to terms with who he was—helped him embrace the simple food of the Deep South he’d spurned as a young cook and, as he implies in the documentary Fried Chicken and Sweet Potato Pie, helped him come out. “What I didn’t realize for the longest time,” Scott says, “was that as Miss Lewis was teaching me to accept Southern food and seeing the uniqueness and to celebrate the wonderful things about that, it’s a way of accepting yourself. When you accept those parts of yourself that are on the outside and you began to see grits as something to be proud of, and equal, then you began to see those things about yourself….It’s a lot bigger than cooking.” Edna helped Scott clear a path to biscuits and self-acceptance.

They met about the time of Edna’s third cookbook, In Pursuit of Flavor. And while she was respected among chefs and aficionados of so-called New American cuisine and of fine Southern cooking, she was hardly the icon she’d become in death. (Especially after January 2017, when an Edna Lewis elimination challenge on Season 14 of Top Chef propelled Edna’s 1976 book, A Taste of Country Cooking, to the heights of the Amazon Best Sellers list.)

Novelist Chang-Rae Lee, visiting for a 2001 piece in Gourmet magazine, says Edna and Scott share a place twenty minutes from Atlanta, in what Lee describes as a “patch of low-rise, older brick apartments…not by any means awful, but the landscaping is tired, and it all seems plain and unspecial, like a small college dormitory.” Lee characterizes their banter and good-natured ribbing as “girl talk.” Scott calls Edna “mother.” He’s painted the bathroom a shade Lee names “Day-Glo pretty-in-pink.”

Edna and Scott are allies anchoring marginal space, carving out their own place of creation and mutual understanding. And mother let me tell you: It is queer as hell.

I can’t tell if this is a throwback for Edna to her friendship with Karl and Johnny, or if creative gay solidarity was somehow a constant in her career. What I know is that Café Nicholson was for a brief moment this inclusive, ego-driven, transformative, way-too-much, colossally queer experiment in creative expression.

*

Edna Regena Lewis was born on a farm in 1916, one of eight children, to a place known as Freetown in Orange County, Virginia, a community founded by the formerly enslaved, including Edna’s grandfather. She begins to learn by watching her mother, Daisy, and others cook. She takes on more and more of the cooking at home.

When Edna’s twelve, during the Great Depression, her father dies. At fourteen she’s already employed as a servant, and at fifteen leaves Virginia to work as a cook for a family in Washington, DC. At sixteen she joins two other young women headed to New York City.

Like Johnny, Edna seems determined to not be stuck.

After false starts, including an ironing job at a Brooklyn laundry from which she was canned three hours after she started, Edna lands a job with the Communist Party as a typist. Have her fingers ever touched a typewriter’s keys? It doesn’t seem to matter. Edna just…takes things on.

Again like Johnny, Edna seems to find in New York City a mecca of independence, a place that affords the sort of liberation impossible in Freetown. She’s political, takes classes taught by the party, attends discussions. She campaigns for FDR. She’s inclined to resist rules that reinforce exclusion: of course racism, but also anti-unionizing, and voter suppression. They were the only ones, she says, referring to the Communist Party, “the only ones who encouraged the Blacks to be aggressive, and to participate.” She gets a job with the Communist paper the Daily Worker, printing subscription labels.

You figure that with her interest in cooking, she might save up enough to dine at a restaurant above the level of cafeterias and the Automat. Despite New York’s lack of formal Jim Crow laws, discrimination against Black diners is common. Below Harlem, a customer who looks like Edna can count on being shown a shitty table behind a partition, or around a corner, near the kitchen or the toilets—hidden, exposed to rude service. It doesn’t matter if you’re famous. In 1951, Josephine Baker publicly blasts Manhattan’s Stork Club after her white companions are served expeditiously while she waits and waits for a steak that never arrives. In the 1980s, Edna becomes chef of Brooklyn’s cherrywood-arched and brass-chandeliered Gage & Tollner restaurant, but four decades earlier, trying to eat there would likely have resulted in humiliation and frustration. In a time before the open kitchen, Black and brown workers were kept on the side of the porthole swing door unseen by the public.

*

I don’t know exactly when Edna meets Karl Bissinger. It’s sometime in the 1930s though, in the years before the war changes a lot of things in New York.

“Edna and Karl were both part of a bohemian crowd, and Communist-adjacent,” Phyllis Eckhaus, friend to both Johnny and Karl, says. Though really, adjacent seems to better describe Karl, scion of a wealthy Cincinnati family that built its fortune on candy. His childhood was painful. He came to New York and enrolled in the Art Students League. His circle of friends, including Edna, had come to the city to shed strained or difficult pasts. “We were bohemians to escape our backgrounds,” Karl once said. They came to New York be free.

Eckhaus guesses that Edna would have met Johnny through Karl.

“We all went to the same parties,” Edna told the writer Susanna Cuyler. “Karl had a lot of records, but usually we’d talk.”

Besides Karl and Johnny—boyfriends sharing a cold-water walk-up near the Third Avenue El, the elevated railway running north and south through Manhattan to and from the Bronx—Edna spends her social hours with artsy boys and girls connected to the Art Students League. It’s a bohemian group, some queer, and all with futures. There’s painter and sculptor Jeanne Owens, who’s also Karl and Johnny’s roommate; photographer Richard Avedon; textile and fashion designer Ken Scott; and painter and fashion illustrator Sylvia Braverman.” (“Sylvia’s mother had a thrift shop,” Edna recalled, “and we’d get dresses there.”)

There’s a lot of drinking at these dinners and parties—you’d need the whole next day to recover—but the food is terrible unless Edna’s cooking. She does simple country dishes, cheap by necessity. Does she make biscuits? Deviled eggs and pickled cucumbers? Sugar cookies and Apple Brown Betty? She gets a reputation as a cook.

Owens, who’s also a competitive swimmer attending international meets, goes to Paris and carries back a jar of gazpacho for Edna to taste. She describes to Edna seeing whole pigs roasted in South America.

For a party, Scott displays different kinds of cookies on a high shelf, a plate rail that runs around a room in his apartment. It makes such an impression on Edna, this outré blending of food and aesthetics, that she’ll recall it in conversation some four decades later.

By the late 1930s Edna’s sewing dresses at home for a New York fashion house. Through a friend of Johnny’s, she gets gigs working on department store windows starting with the big Christmas displays. She’s building chicken-wire forms, sewing satin backdrops and covering them with sparkly stones and peacock feathers.

Edna’s surrounded by progressive politics and Black activism. She’s getting jobs as a seamstress, sewing her own clothes, and she finds new employment, ironically, working in the most frivolously sybaritic centers of Manhattan capitalism: the luxury department stores along Fifth Avenue. She picks up gigs assisting the window dressers at Bonwit Teller, surely one of the queerest occupations in the city.

At Bonwit, Edna surely works for Gene Moore, the window artist who came to work for Bonwit in 1945. Moore’s signature was a spare, rigorously narrative style. (He would become legendary in coming decades for his work at Tiffany on Fifth Avenue. In fact, it’s Moore’s low-sheen spangled windows that Audrey Hepburn, as Holly Golightly, munching a cruller and sipping a coffee, gazes into—and through which we gaze at her—for the opening credits of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.)

What’s consistent in Edna’s life, and Johnny’s and Karl’s too, is resisting the sort of life that kills expression.

Meanwhile, Johnny’s work on the windows at Lord & Taylor was ruled by another master of the form, Henry Callahan.

Both Moore and Callahan lean on dramatic light and shadow to focus the gaze. Windows by both men show an affinity with the eye of George Platt Lynes, the queer photographer of dancers and male nudes. They seem to quote the surrealist photographs of queer British photographer Angus McBean. They sometimes slip in wacky elements, as in Moore’s two-headed mannequin for a Bonwit hat display; the heightened stories in the staging of mannequins and props recalls the magic realist tableaus of the painter Paul Cadmus, where narratives of men about to hook up weigh as heavy in the air as muggy weather.

Look at the female mannequins in a 1947 Bonwit window, in a series featuring art on loan from the Guggenheim, known then as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. The window shows two stylish women (one somewhat older, the other young, fresh, sassy) in an art gallery before a huge Rolph Scarlett painting, captured in the moment of discovering they’re both wearing B. H. Wragge dresses in different styles but sewn from the same print fabric. The mannequins’ body language shows surprise, peevishness, but also a kind of shared attraction, as if showing off their figures to each other. As if demanding, “Who wears it better?” As if signaling that halfway through a pitcher of martinis in the older mannequin’s apartment, those dresses are coming off.

For me it’s an easy jump from Gene Moore’s strict visual editing to Edna’s later pared-down yet luxurious culinary style. In Edna and Johnny’s creative and cultural education, sexual desire is an invisible engine driving a compulsion to buy a smart new peplum jacket or pair of long evening gloves. Longing that cannot show itself in daylight becomes an urgency for other experiences, including taste: meeting sensuality in rich, delicious things.

Toward the end of 1947, thirty-one-year-old Edna marries Stephen Kingston, an ex-merchant seaman who’d apparently worked as a cook for a company of Marines stationed in San Francisco. He’s a Communist Party leader in Brooklyn’s Stuyvesant Heights neighborhood, working with the party’s African American coalition on labor and civil rights. He’s also on the local council of the National Negro Congress, fighting employment discrimination in Brooklyn. Earlier, Kingston was part of the Communist Party’s vigorous defense of the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama, and authored a 1941 pamphlet on abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

I imagine Edna’s life feels like slipping in and out of two parties happening at the same time in side-by-side apartments. In one she’s hooting and drinking and (I am sure) hearing every scandalous detail with unfiltered queer boys like Johnny. Next door in the other she’s talking race and class oppression with earnest heterosexual comrades. (Well, publicly heterosexual—the American Communist Party denounced homosexuality in 1938 as a sickness of the bourgeoisie, denying membership to any and all known queers.) I mean, Karl and no doubt other gay friends of Edna’s were communists, but sort of—I don’t know, secular commies, without the orthodoxy that must have reigned in the offices of the Daily Worker.

Still, what’s consistent in Edna’s life, and Johnny’s and Karl’s too, is resisting the sort of life that kills expression. What’s consistent is a commitment, if you’ll indulge me in calling it this, to queerness.

__________________________________

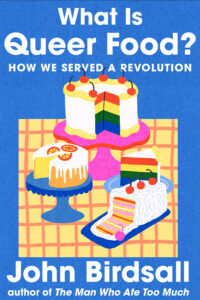

Reprinted from What is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution by John Birdsall. Copyright ©2025 by John Birdsall. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

John Birdsall

John Birdsall is the author of The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard and the recipient of two James Beard Awards for food and culture writing. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.