How Does the Great Dolly Parton Write a Song?

Lydia R. Hamessley on Memory, Musical Storytelling, and "Coat of Many Colors"

“All of those little pieces of your past, they’re all important. That’s why I’m so thankful I can write songs. I can capture all those memories in my songs and keep those memories alive.”

Songwriting always came easily to Dolly Parton. Her father recalled “she was writing songs before she knew how to hold a pencil.” Dolly described her childhood fascination with rhyme, rhythm, and the everyday sounds she made into music:

Since I have been able to form words, I have been able to rhyme them. I could catch on to anything that had a rhythm and make a song to go with it. I would take the two notes of a bobwhite in the darkness and make that the start of a song. I would latch on to the rhythm my mother made snapping beans, and before I knew it, I’d be tapping on a pot with a spoon and singing. I don’t know what some of this sounded like to my family, but in my head it was beautiful music.

Dolly wrote her first song when she was around five. “Little Tiny Tassletop” was about her doll made from a corn cob, dressed in corn husks with corn silk for hair, with two brown eyes burned into the cob with a hot poker:

Little tiny tassletop

I love you an awful lot

Corn silk hair and big brown eyes

How you make me smileArticle continues after advertisementLittle tiny tassletop

You’re the only friend I’ve got

Hope you never go away

I want you to stay

Dolly’s mother was impressed with her rhyming ability and kept this song tucked away for years. Dolly has since sung it, always in a little girl voice, on television shows for children and in interviews about her early songwriting. She often concludes the song with a giggle, saying “Well, what did you expect? I was just a little kid!” or “I told you it was corny!”

In addition to rhymes, Dolly loved creating musical sounds, and she was inventive about making instruments to inspire and accompany her melodies. When she was about six, she would play around with a dilapidated piano in an old church. Dolly recalled: “I found an old wooden mallet in the smokehouse. I had wrapped a rag around it to soften the blow, and I would beat on those strings in that old piano. And I would get that old droning sound, and it made a really good sound, and I would just make up melodies with that.” She also remembers “rigging up an old mandolin that the neck was gone. I had an uncle that had a sawmill up the road, and I had him build a board underneath it. And I had stretched some strings over that. I don’t know if they were the bass guitar strings or something I had cut off the piano.” Dolly would “bang on” these strings with a stick or, less often, strum with her thumb to create drones, like she did with the old piano: “So I would just make my melodies around sounds. And so anything that I could rig up to make a little different sound in addition to the other instruments, I would just do that.” Dolly most enjoyed creating drones, and these sounds were the sonic underpinning over which she spun her melodies.

Dolly loved creating musical sounds, and she was inventive about making instruments to inspire and accompany her melodies.

Dolly’s songwriting began in earnest when she got her first “little baby Martin” guitar when she was about seven or eight: “that’s when I started to write some serious songs.” At around the age of eight or nine, Dolly wrote “Life Doesn’t Mean Much to Me” after overhearing her mom and aunts talking about young men who had been killed in war. It is a sophisticated lyric for a child of that age with its rich imagery, consistent rhyme scheme, and refrain. She called it “a pretty deep song for a kid. Don’t ever remember thinking like a child.”

He’s gone from my world

Left this country girl

To fight in a war ’cross the sea

The telegram said

He’s been pronounced dead

Life doesn’t mean much to meArticle continues after advertisementWhat good is life

Without him by my side

Just lay me beside where he sleeps

My soldier boy’s gone

Left me all alone

Now life doesn’t mean much to meGoodbye one and all

The river has called

I’ll be with him eternally

Life doesn’t mean much to me

Dolly’s storytelling gift is evident here. She drops the listener immediately into the scene, lays out the emotional response to the soldier’s death and, in a characteristically Dolly move, surprises the listener with a sudden and stunning conclusion. Looking back on the song, Dolly said, “I guess I’d hear them talk about people drowning themselves and heartbroken girls and all that. But at any rate those were serious songs at the time. And I was serious about it even though I did write some fun ones as well.”

From these charming and humble beginnings, Dolly estimates she has written over 3,000 songs, and over 450 of them have been recorded. Her songwriting has been recognized with numerous awards, including her induction into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1986 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2001. Dolly consistently asserts that songwriting is her first priority and being a songwriter is her primary identity. I explore Dolly’s approach to songwriting: what inspires her, what is her process? I also use her iconic song “Coat of Many Colors” as a touchstone through which to explore the way she shapes and reshapes pivotal stories of her life through her songs. Although not all of Dolly’s songs are autobiographical, they are often informed by her life and the people and situations she observes. She turns memory into song.

*

Whenever pressed to choose her favorite song, Dolly always names “Coat of Many Colors,” which is about a true story from her life. As a young child, she lacked a suitable coat for the winter, so her mother sewed one out of scraps given by neighbors. To make the homemade garment special for Dolly, she told Dolly the Bible story of Joseph and his coat of many colors. Dolly ran off to school, proud to show it off. But Dolly’s classmates made fun of her, teasing her about her coat made of rags.

Many years later, in 1969, she composed the song about this incident. With its folklike melody and simple three-chord harmonic structure, the song’s first-person account of these events draws listeners in to an intimate story of childlike innocence, pain, and grace. Dolly did not record the song immediately, and in the intervening time Porter Wagoner recorded it on two occasions in 1969, with Dolly apparently singing backup. Dolly’s recording was released in 1971 on her album Coat of Many Colors; the song went to #4 on the country chart, and it appears on many of her compilation and greatest hits albums. No live concert of Dolly’s would be complete without it.

Whenever pressed to choose her favorite song, Dolly always names “Coat of Many Colors,” which is about a true story from her life.

Dolly also published the lyrics as a children’s book in 1996. In 2016, she released a new version of the book as well as a made-for-television movie, Dolly Parton’s Coat of Many Colors, seen by over 15 million viewers. Dolly read the lyrics of the song as a bonus track on her 2017 children’s album, I Believe In You. The song’s melody hovers behind Dolly’s voice, its music box timbre suggesting childlike innocence. In 2011, “Coat of Many Colors” was inducted into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress, whose purpose is “to maintain and preserve sound recordings and collections of sound recordings that are culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” The song was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2019.

Why does “Coat of Many Colors” have such wide-ranging popularity, and why is it “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”? To begin with, the song is Dolly’s version of a story from her life, which audiences value, believing that autobiographical songs are more powerful and emotionally honest. Moreover, the song is primarily from the perspective of a child, which simultaneously takes listeners back to their own memories and arouses their empathy. That a mother plays such a pivotal role in the song, both as the giver of a precious gift and as the source of a deep reservoir of love, heightens the poignancy of the story. Listeners can also place themselves in the scenario as the teased child or the loving parent.

The aesthetic significance of “Coat of Many Colors” is not only measured by its compelling “true” story that allows us into Dolly’s “real” life, but also its pliability which makes it an allegory. Most listeners can relate to the pain and embarrassment of being teased as a child, even if they have never lived in poverty. Dolly reports that the song is taught in schools to address bullying. “Sometimes they simply sing the song and discuss it. Other times, the children make their own coats with construction paper, each square representing something in their lives. It really touches my heart to think that the song is being used to teach respect and tolerance. I’m proud that in a small way my little song has helped so many people.”

The aesthetic significance of “Coat of Many Colors” is not only measured by its compelling “true” story that allows us into Dolly’s “real” life, but also its pliability which makes it an allegory.

Through “Coat of Many Colors” we discover why composing is essential for her. Dolly’s songs constitute a memory palace—a place to store her memories in lyrics and melodies that evoke people, feelings, places, and events, bringing them to life whenever she sings one of her songs. Of course, not every song is based on Dolly’s life. She is often inspired by other people’s lives and experiences, and she writes some songs without calling on specific memories or events. But, a big part of Dolly’s songwriting is to keep memories alive, and she points to “Coat of Many Colors” as one example: “Whenever I sing that I just see my whole childhood.” The song—like a teddy bear, a blanket, or the multicolored coat itself—is a transitional object that links the child to its mother. For the three minutes Dolly inhabits the song, she is that little girl, as well as the adult who, decades after she wore the coat, conjures up her mother’s love, re-creating their bond and extending it into the present.

__________________________________

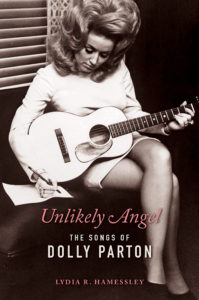

From Unlikely Angel: The Songs of Dolly Parton by Lydia R. Hamessley. Copyright 2020 by the University of Illinois Board of Trustees. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

Lydia R. Hamessley

Lydia R. Hamessley is a professor of music at Hamilton College.