How Do You Deliver a Baby in the Middle of a Storm with One Generator, No Water, and No Electricity?

Belle Marie Torres Velázquez on Working as a Medical Doctor on an Island of Puerto Rico and Surviving Hurricanes Irma and María

THE ISLAND’S ONLY DOCTOR

My father is a doctor in San Juan. My mother was a pharmacist, but with four children, having a family and a separate job was a handful. When I was five years old, she decided to join my father’s clinic. So, we kids started going to the office to be with them every day after school. They had a cozy room just for us with a little kitchenette for snacks, but whenever my father could, he’d show us something interesting or ask us to assist him. He’d call and we’d run shouting, “It’s my turn to help!” Today, my sister, Rina, and I are both doctors. Our training started there.

I’ve worked for the health department of Puerto Rico for many years. For most of that time, I was assigned to different urgent care centers around the main island. My husband and I lived in the town of Carolina, but I had to travel to wherever they needed a doctor. It was a very hectic life for me. Six years ago, when I was pregnant with my second child, we had the opportunity to move to Culebra. Here you’re surrounded by nature: everything is green with trees and mangroves. There’s no place in Culebra where you don’t see the ocean. And there are only 1,800 people who live on this island full time. Everybody knows each other here—maybe not by name, but you know who they are, where they live, where they work, or what they do. I really wanted a quieter, more stable place for us.

After we moved here, though, I got divorced. Suddenly I was a single mother of two and the island’s only doctor. I knew going back to the main island would mean relying on somebody else to help me take care of my children while I was at work, and I didn’t want that. I do have people here that help me, because I need to be in the clinic a lot, but it’s different because I live only ten steps from the clinic. The kids are so close to me that I can just walk two minutes and stop in to say hi.

Culebra is not for everyone, though. Sometimes other doctors fly in from the main island to relieve me, and sometimes they fly out before their time is done and don’t tell anyone! If the other doctor leaves, the nurse has to run to my house and knock on my window. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night, hearing, “Come quick! The other doctor left, and now there’s an emergency!”

Our clinic is very small, and we’re not equipped to admit patients. We don’t have a birthing unit and we can’t provide long-term care. Usually all of our emergency patients are evacuated to the main island. If we hear that there might be tropical storms or hurricane weather, we take precautions and evacuate all patients who need special care, along with the pregnant women who are near their due date. We’re not prepared to care for women if they go into labor here. For the past 12 years, no baby has been born on Culebra.

For us, Hurricane Irma was worse than María. It became completely silent and still before Irma arrived—there wasn’t even a breeze—and then all of a sudden, the winds were roaring. Like something was in the walls howling at us. When I peeked out at the storm through a small part of the window that wasn’t covered with a shutter, I could see the ocean covering the ferry docks and the ticket booths, coming up into the street. It arrived as a Category Five hurricane and took down all of our trees and most of our houses, which were mainly wooden and went down easily.

After Irma, we did have some help from the government because Irma didn’t impact the whole of Puerto Rico as much, but the ferries weren’t running so they couldn’t get the equipment over to clear the roads. Some people here had tractors, though, and neighbors were helping neighbors. They were gathering up all these broken house pieces, appliances, furniture, trees, debris, or just plain garbage and piling it all up for eventual removal. It took about one full week after Irma for us to regain contact with the main island, and, by that time, they were starting to talk about María. So, when she finally came there wasn’t much left to destroy!

All those same feelings of desperation are inside me still.

The emergency room of the clinic was also severely damaged in Irma—a projectile broke the zinc roof—which was very worrisome because it’s the only urgent care on this island. The emergency room generator also broke down during Irma and nobody could turn it back on. Everyone tried—staff, police, fire, well-meaning friends—but it was dead. There was another generator on the clinic side that was working, and we were running extension cords from the clinic to the cardiac area of urgent care so that we could at least have the resuscitation equipment available for emergencies.

After five days of the emergency machines being run by extension cords, the mayor let us move into another building nearby—that’s what we’re using now and where we’re sitting today. This was an office building with small rooms, but we had no other choice, so we marked off some of the offices to be a makeshift emergency room. It was better than nothing, but we kept having to go back and forth across the parking lot to the old urgent care for supplies. When María came, we still didn’t have electricity and we were working around the clock with the one generator.

As I’m speaking, I have goosebumps on my arm. All those same feelings of desperation are inside me still. For a long time after the hurricane, there was no electricity, the public schools were closed, transportation was next to impossible, and there was no communication. There is no potable water on Culebra, and we have only a few family farms, so all our supplies had to be flown in, too. In those days, we kept one nurse with me on each shift. We couldn’t do more because there were so many problems everywhere you turned and because everyone had so much to attend to in their own lives.

I FELT A BEATING HEART

After two months like this—with one generator for the whole clinic, no electricity, no water, and me as the only doctor working with just one nurse—the nurse came to tell me, “There’s a pregnant woman here and she has pelvic pain. What do you want to do?” I know that this pain could be anything. So, when I went out to the waiting room to talk to the woman, I wasn’t too worried at first. I have a list of the pregnant women on Culebra for evacuation purposes. And we had evacuated all the people who were at least eight months pregnant, near their due date. I called each of these women personally and we provided transportation to the main island for them and their families. But this person, Neysha, was not called because she was only seven months pregnant and showed no signs of any high risk. She was nowhere near her due date and not having any problems.

We met and she began to describe her pain, but while she was talking, she kept pausing, putting her hands to her side with a distressed look on her face, and it looked like she might be having contractions. And what she was describing sounded a lot like labor pain. I started thinking to myself, Dear God, this cannot be possible.

I was growing concerned because I knew there was absolutely no possibility for me to evacuate her. But when I brought her back to our makeshift exam room and proceeded to examine her, I found that she was ready. I finally stopped talking and said, “Enough. We need to get the stretcher.” I needed to get her off the exam table and in position for the birth. But the stretcher wasn’t even a stretcher for giving birth. It was a regular one that couldn’t accommodate our needs, so it was harder for her and for us. And the room we were in is not that big. If I’m being generous, that space was about seven feet by eight feet, and in it we had the stretcher and an oxygen tank and there was a crash cart behind my back. So, it’s a small room with a lot of equipment, the mom, me, and the nurse. We didn’t really have the space to move, let alone deliver a baby.

Honestly, I was hoping that she wasn’t giving birth. The circumstances were too grim. But that wasn’t the reality. This baby was coming, and it was coming now. It wanted out! There was nothing I could do. I just kept praying in my mind because I’m a general practitioner, not an obstetrician. This was my first birth since medical school. When you’re a student, you need to assist in a certain number of deliveries in order to graduate, but I didn’t go into that specialty, so this was my first birth in years. This baby was coming under very poor conditions—with no access to special equipment, no transportation, and no possible communication with an obstetrician.

We didn’t have a way to communicate other than satellite phone. In order to use it, you have to go outside, point it at the right angle to pick up a signal, and then hope that there are no clouds to interrupt the signal. So, there was no way to use the phone and deliver the baby. No way that someone could guide me through the birth.

We looked at those teeny feet and we were scared, but we had no choice and just had to proceed.

When the baby started to come, what we saw were toes and not a head. This baby was coming breech, which means that the legs are coming first and not the head. This is not typical. Usually when a baby is carried to term, it turns on its own so that the head is downside and the first thing that will come through the vaginal canal will be the face. This happens because of the baby’s need for oxygen. It’s also better that way for the umbilical cord. If the baby comes out headfirst and the cord is around the neck, you can untangle it and help the baby, but you can’t do that when the baby is breech.

Under this circumstance, many OB/GYNs will just do a C-section. If they know by a sonogram that the baby’s breech, they don’t do the vaginal delivery. But in our case, we didn’t have a sonogram or any type of imaging. We didn’t know the position of the cord or anything at all. There was no way we could know if the baby was even still alive. We didn’t have any equipment! The nurse and I looked at each other; we were communicating our concern with our eyes, knowing that this birth would be chancy. We looked at those teeny feet and we were scared, but we had no choice and just had to proceed.

In the beginning, Neysha was doing fine. Most of the baby was out—we could see it was a boy—and she was pushing. She didn’t seem to be feeling pain despite us not having an epidural for her. She was relaxed, but very tired and just wanted to sleep. But the baby wasn’t out yet. He was stuck at the shoulders and his head was still inside of her, and we were worried. I thought about God and asked him to use my hands. Neysha looked at me and asked, “Is everything all right?” I met her eyes and told her, “Everything’s fine, but you need to push a little bit harder. Can you push one last time? Really hard.” But the nurse motioned to me and her eyes were very large. She shook her head, no. She was giving me the sign that she thought the baby was dead. It was cyanotic. The baby was blue. He wasn’t breathing.

I reached over and put my hands on the baby’s tiny shoulders. With my right hand, I searched his little body and prayed to God, until I felt a beating heart. “This baby is alive, and it’s coming!” I cried. I told Neysha again that everything would be fine. She still had work to do and needed to be calm. “The baby is fine, and you are going to birth him now.” So, I really pressed her belly and told her, “Push as hard as you can!” And we got the baby. He came out all at once in a rush, smoothly. And he was alive. He cried right away, as soon as he was free. His coloration quickly came back to normal and everything was perfect after all. We placed the baby in an incubator that we powered by generator. He was two months early, but he was alive!

And then I started to try to find help to transfer Neysha and her newborn to the main island. By protocol, both needed to be in the hospital. But it was almost impossible to contact any planes or hospitals.

I was using the mayor’s satellite phone, as, at that time, he was the only one on the island who had one. The health department had given us a satellite phone maybe five years before I even arrived on Culebra, but no one on the staff was told how to maintain it. It has a chip in it that expires yearly. So, we thought we had a satellite phone for emergencies, but it was just for show; it didn’t work.

When I was finally able to get through to the hospital, I learned that transportation by their helicopter was out of the question. The air ambulance has many specifications for flying. If there’s wind or if it’s too cloudy, they cannot come and pick up a patient. It was raining hard, so the conditions were too dangerous. We sent a driver to the police station with a handwritten note that said, “Please contact the police on the main island for a rescue helicopter! We have a newborn baby that needs to go to the hospital immediately!” And the police were finally able to give us that assistance.

HELP STOPPED COMING

After María, so many doctors left Puerto Rico that they had none left to send to Culebra. Help stopped coming. Since I was the only doctor on the island throughout that whole time, all patients were my responsibility 24 hours a day. We had injuries from the hurricane that were never tended to and then new injuries from the cleanup. We saw so many skin infections in those days. And that was all on top of the regular things like refilling prescriptions and tending to our patients with chronic conditions. It was hard to be on duty for so many consecutive hours. I don’t remember how many “Dear Fathers” I threw out during those days, but I kept saying, “Please, God, use my hands to help others.”

And, finally, my own father came to our rescue. He’s 74 now, but still has his own clinic in San Juan. He doesn’t have a generator there, though, so it remained closed for a long time after the hurricane. At first, the police boat would bring him from San Juan to work with me in the clinic, then he used the ferry when it started running again. It was 21 days after María before transport between Culebra and the main island was even partially restored. And, even now, he’s still coming to help.

Today, the clinic is rebuilt, and it even has a permanent roof. The first clinic was opened over 30 years ago and, since then, the staff had to move out of the building and set up a temporary care site whenever there was a storm warning because the zinc roof wasn’t safe. After Irma and María, that was unacceptable. And I told that to everyone from the government who came to inspect our clinic. “It’s a shame you haven’t paid for the roof,” I’d say. And they’d answer, “Keep holding on. Maybe one day.” But some nonprofit organizations, a foundation, and even individuals came together to help us with the money, and I finally have a cement roof. Of everything we’ve done to rebuild, I think I’m most proud of that roof.

__________________________________

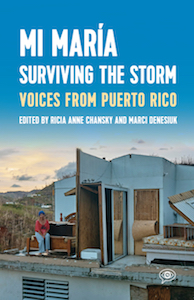

Excerpted from Mi María: Surviving the Storm, Voices from Puerto Rico, edited by Ricia Anne Chansky and Marci Denesiuk. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Haymarket Books.

Belle Marie Torres Velázquez

Belle Marie Torres Velázquez is the only doctor on Culebra, an island municipality off the eastern coast of the Puerto Rican archipelago.