How Do We Prepare Boys for Healthy Relationships?

Emma Brown on the Importance of Meeting the Emotional Needs of Children

The work of preparing boys for healthy relationships often has nothing to do with sex at all. Often it is about helping kids navigate some of the trickiest parts of being human—balancing what you want against what others need, taking responsibility when you mess up, rafting emotions without being swamped by them.

I have never seen these skills taught more deftly than by the fourth grade teachers at Maury Elementary in Washington, D.C., a school I’ve reported on for years. On one visit, on a windy morning under blue skies, students learned how they had fared in the lottery that determined where they would go to school the following fall. In a city where public school choice means many kids scatter after fourth grade, it was intense. Some students were nearly vibrating with excitement, having gotten into their first choice; others had been disappointed, and were crumpled and teary.

One boy with freckles and a chapped upper lip was so upset that he had to go outside and breathe. When he came back inside, he gave his teacher, Vannessa Duckett, a hug and slipped into the classroom. What I was seeing was evidence of a transformation, Duckett told me. A few months earlier, the boy’s feelings regularly boiled over into angry outbursts. Now, he knew how to recognize those feelings and deal with them.

The boy told me that what changed for him was his teachers’ focus on social-emotional learning, or SEL. In some conversations, SEL can be one of those abstract educational acronyms that no one can quite define. It encompasses a huge range of programs meant to foster children’s sense of determination and responsibility, as well as their ability to manage emotions, relate to others, and solve problems.

But to the boy at Maury, it had a very specific meaning: the concrete skills he had learned to deal with the storm of feelings and interpersonal drama that come with being a nine-year-old (and, more generally, a human being). He had learned not only to breathe when he got upset but to use “positive self-talk,” he told me, and to talk to a friend.

“I’ve learned how to manage my feelings,” he said.

The work of preparing boys for healthy relationships often has nothing to do with sex at all.

If we care about preparing our boys for healthy relationships, this may be one way to do it—making time and space in school, where so much of their social world exists, to teach them how to name and handle their emotions and solve problems that crop up among friends. Creating a classroom culture where students are expected to think about how other people feel and notice what they need, and to be as earnest about kindness and empathy as they are about academics. Helping them see that while it takes practice to learn how to navigate our inner lives and our social lives, it is something we all can—and should—learn to do.

For most of the last two decades, public schools had little incentive to focus on these human skills because they were judged and sanctioned almost solely according to students’ performance on standardized reading and math tests. A new federal education law, passed in 2015, has broadened the definition of school success, making more room in the curriculum. At the same time, a growing body of evidence has bolstered support for teaching social and emotional skills, showing that it can produce stronger academic achievement. The result has been endorsement by the federal government and funding from the likes of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Social-emotional learning can improve a range of children’s skills, including their ability to recognize emotions, solve problems, make decisions, and demonstrate empathy, according to a review of more than 200 programs involving 270,000 children in kindergarten through high school. The few studies that measured impact on academic achievement found that social-emotional learning also made a difference in kids’ ability to learn. Longterm, kids who got this kind of instruction were more likely to graduate from high school and college, less likely to get pregnant or contract a sexually transmitted infection, and less likely to be diagnosed with a clinical mental health disorder.

The CDC lists social-emotional learning in K–12 schools as one strategy for preventing sexual violence, and some programs have shown promise for directly addressing sexual harassment. Second Step, a social-emotional program for middle schoolers, contributed to a 56 percent decline in homophobic name-calling and a 39 percent decline in sexual violence in one of two states where it was tested.

Skeptics question whether schools should spend time on soft skills when kids—especially poor kids—need so much improvement in hard academics. “Emotional learning will be the downfall of society,” reads the headline of a 2018 opinion piece in the right-leaning publication Townhall, written by Teresa Mull, a fellow at the conservative Heartland Institute. “SEL teaches kids to feel and not to think,” Mull wrote. “Of course, feelings themselves are not bad or dangerous, but they can be when they aren’t tempered with a sense of right and wrong. Traditional public schools, apparently determined not to teach kids history, how to read, spell, add, subtract, multiply, or anything useful, instead take on a role of psychotherapist (and not a good one).”

If we care about preparing our boys for healthy relationships, this may be one way to do it—making time and space in school, where so much of their social world exists, to teach them how to name and handle their emotions and solve problems that crop up among friends.

Social-emotional learning can certainly be done poorly, as can anything in schools. I know that from teaching middle school math early in my career and from covering education for most of my journalism career. But it can also be done powerfully, as at Maury, where fourth-graders are developing the vocabulary, experience, and confidence they need to navigate relationships and internal storms of emotion.

The boy with the chapped upper lip told me that in third grade, there was a lot of pushing and bullying. It was terrible, but no one ever told the teachers about it, and so it continued. Now, things were totally different. In fourth grade, his teachers’ relentless focus on seven skills had helped kids be more kind to one another: courage, consistency, persistence, optimism, resilience, flexibility, and empathy.

I asked him which of the seven skills he’d been working on.

“Optimism. Also consistency. But I would say optimism is a little harder since my sister is annoying,” he said, without cracking a smile. “It’s hard to stay hopeful that she will stop.”

He and his classmates—a diverse group both racially and socioeconomically—are not suffering academically. Their math and reading test scores are improving in the fourth grade, not declining.

I first met Duckett in 2014, when I was covering DC schools for the Post. A two-decade veteran of the classroom, she told me then that she had initially been skeptical of social-emotional learning. It seemed so fuzzy, so nebulous. But she was converted when her fourth-graders piloted Roots of Empathy, a Canadian program that brings babies into classrooms to teach kids how to recognize and deal with emotions in themselves and in their peers. Studies have found that Roots results in less aggression and bullying and more sharing and cooperation. Duckett found that the visits from the baby had helped her create an environment where kids were less likely to misbehave, more available for learning— and kinder to one another.

Since then, Duckett and her teaching partner Abby Sparrow, who together are responsible for about fifty kids, have doubled down on socialemotional learning. At first, they were just looking for a way to improve academic achievement and classroom harmony. Then they started to see their work as something much bigger. “This shapes who they will be in marriages and in the workplace,” Duckett said. “I hope part of what we’re raising them to believe is they should have deep, meaningful connections.”

Social-emotional learning can certainly be done poorly, as can anything in schools.

Besides hosting the baby in their classroom for Roots of Empathy, Duckett and Sparrow devote the first two weeks of school to helping their students understand the seven skills they want them to learn. And every Friday morning is dedicated to social-emotional learning, including the elementary school version of Second Step and a ceremony for recognizing students who demonstrate one of the seven skills. They are rewarded with a coveted foam crown—and a long, detailed, appreciative narrative from their teachers, delivered in front of all the other kids, about what they did to earn recognition.

Duckett and Sparrow are not working in a vacuum. Their whole school is attuned to the social and emotional needs of children, and in particular those who have been through the kind of trauma that can interfere with their ability to learn. Struggling children are paired with adults in the building who are not their teachers; they meet once a week, sometimes to talk about academic goals and sometimes just to play a board game and talk. The point is to open up avenues for children to build the kinds of trusting relationships that can buffer them from the effects of their adversity, including their propensity to act out violently.

Duckett and Sparrow also pick a few children each year—often kids who have more than their fair share of pain or difficulty at home—whom they ask to join a lunch club. Those children get to eat with their teachers once a week, and go on an outing—to a movie, or ice-skating, or a museum—once a month. It’s another way to build the kind of relationships that can help inoculate a child against the toxic stress in his or her life.

In my visits, I saw that the power of these two teachers’ approach lies less in any pre-cooked curriculum than in the fact that two tough, deeply adored teachers treat social and emotional skills as if they are just as critical as math, reading, and writing. They have created a common language to describe the aspirations they have for their students, and they constantly reinforce those aspirations.

“What matters the most to Ms. Sparrow and Ms. Duckett is kindness, caring, and not giving up,” one of their students said in June, explaining to a group of third-graders what they could expect the following school year. He said when he moved up to fifth grade, his goal was to keep working on “feeling what other people are feeling.”

Their whole school is attuned to the social and emotional needs of children, and in particular those who have been through the kind of trauma that can interfere with their ability to learn.

Whenever a student throws a tantrum, or does or says something disrespectful, he has to reflect in writing on what he did, what he was feeling when he did it, how he’s going to make amends, and what he’s going to do differently next time.

“I used to get a lot of reflections because I didn’t know what to do when I got angry,” one boy told me. Now, he said, “I usually breathe. It really calms me down. Sometimes, I just walk away.” It wasn’t just anger he had learned to manage. On one of the days I visited, he knew he was feeling really sad, and he dealt with it by asking Sparrow for a hug—in front of the whole class. In the fourth grade at Maury, it was not embarrassing for boys or girls to have feelings, or to need comfort.

Figuring out how to negotiate life with classmates and friends is not actually all that different from figuring out how to negotiate a relationship with a lover, and class discussions organically go places that will prepare these kids for romantic encounters—without their talking about sex at all. On the wall hang artifacts from these discussions: A handwritten poster on what consent sounds like (Yes! Okay! Sounds great! Let’s do it!), when it’s necessary (giving hugs, borrowing things, touching another person, eating their stuff), what you do if you don’t want to give consent (Nope. Stop. I’m good. Maybe later. I don’t like that. No.). Another poster on handling uncomfortable situations—express how the other person made you feel, and make a request for how they should act next time.

On a visit close to the end of the year, one boy told me that he had learned in fourth grade to be more courageous about admitting when he messed up. “If you don’t own up to your mistakes, you can lead the problem further,” he told me. Another acknowledged that he needed to work on being less selfish. And yet another wrote, at the end of the year, that he had learned a lot about being open to taking help from other people. “I started this year not wanting help,” he said. “Now I love getting help.”

It’s hard to see how teaching these skills—managing anger, holding oneself accountable, resisting the urge to be selfish, dealing with uncomfortable personal situations, asking for help when you need it—could lead to the “downfall of society.” And easy to see how they could be helpful to boys— and girls—as they make their way through relationships, and through life.

__________________________________

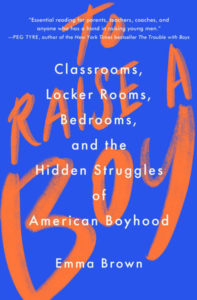

Excerpted from To Raise A Boy by Emma Brown, with permission of One Signal/Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Emma Brown.

Emma Brown

Emma Brown is an investigative reporter at The Washington Post. In her life before journalism, she worked as a wilderness ranger in Wyoming and a middle school math teacher in Alaska. She lives with her husband and two children in Washington, DC.