How Do We Move Beyond Commodified Feminism?

Charlotte Shane on the Dangers of Going Mainstream

If you feel like feminism is failing you, you are not alone. I sometimes have the impression that I’m as thoroughly feminist as I am thoroughly human, that feminism is as intrinsic to my constitution as my skeleton is to my body. But in my 35 years, I’ve struggled with or outright rejected feminism on several occasions: first, as an ignorant adolescent (“What do women need feminism for if we’ve already got the vote?”); then, as a sex worker who saw how regularly and even gleefully feminists stoked the public’s long-standing antipathy toward professionally sexual women; and now, again, as someone moving ever further into the far left, who cannot abide the forms of feminism that embrace and are complicit with the worst aspects of liberalism. The more I learn about the intersecting, oppressive forces that continue to shape the Western world—colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, xenophobia, and racism—and the network of cruel social machinery to which these systems give rise—incarceration, crippling debt, disenfranchisement, deportation, and so on—the less sense it makes to use gender as the primary lens through which to regard human-engineered suffering. Feminism doesn’t feel like the sharpest weapon to wield against white supremacy or border policing, for instance, or even the best tool with which to approach basic civic concerns like vibrant schools. That’s not because those issues don’t impact women; obviously, they directly and indirectly impact many. But they don’t necessarily impact women more or in dramatically different ways than they do men. In other words, the most significant challenges those issues present aren’t tethered to one’s sex. And so prioritizing gender above other aspects of identity limits one’s realm of ethical response.

Here’s an example. American prisons often keep female prisoners shackled while they give birth. There are variations on the theme: Some women are shackled during labor, some are unshackled during but then shackled again almost immediately afterward, and almost all are shackled while heavily pregnant. There’s some variation of what shackling entails, too. It can mean being cuffed at the wrists, or at the ankles, or both—or cuffed to a hospital bed, or chained at the waist. Articulating these details makes the sadism even starker.

A class action federal lawsuit in 2017 alleged more than 40 women at the Milwaukee County Jail suffered this horror. It was preceded by lawsuits in 2014 and 2016 against the same jail for similar practices. But the appalling practice is hardly confined to one city or even one state. In 2015, New York prisons were found to be shackling prisoners in labor in spite of a state law that made it illegal to do so. And according to a 2016 report by the Prison Birth Project and Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, jails and prisons in Massachusetts were guilty of similar violations.

Most feminists probably agree that this is a feminist issue; the topic accordingly receives coverage on feminist websites and sometimes in women’s magazines. But does a feminist obligation to attend to the rights of the imprisoned extend only as far as pregnancy and labor? Is it a feminist issue when a nonpregnant woman is shackled? Or when she is caged for years and exploited for her labor, denied face-to-face visits from loved ones, held captive in a compound in the name of “ justice”? If the answer to these questions is yes, then is it also a feminist issue when men are shackled during various health emergencies—seizures, say? (In 2014, a male inmate in Colorado died after undergoing several seizures while in restraints and receiving no medical treatment.) Is it a feminist issue when incarcerated men are denied the right to visit with family, or exploited for their labor? Is it a feminist issue that so many men are raped while in prison? Or does feminism’s responsibility begin and end with gender-based mistreatment?

“The more I learn about the intersecting, oppressive forces that continue to shape the Western world—colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, xenophobia, and racism—and the network of cruel social machinery to which these systems give rise—incarceration, crippling debt, disenfranchisement, deportation, and so on—the less sense it makes to use gender as the primary lens through which to regard human-engineered suffering.”

The feminists hired by prominent media outlets often advocate for measures that would result in higher levels of incarceration. They write op-eds in favor of further criminalization around sex work, and call for longer prison sentences for men convicted of assault—which we’ve known for decades is not necessarily synonymous with “men who’ve committed the crime.” They also, disturbingly, relish the theater of sentencing like that enacted by Judge Rosemarie Aquilina, who told serial sexual abuser Larry Nassar that if she could, she would “allow some or many people to do to him what he did to others.” (So, sexual violation is an atrocity . . . unless it happens to the right person?) They capitalize on women’s justified fear and anger around mistreatment by men to shore up the status quo, to suggest that our current problems are not the result of fundamentally unjust institutions, but rather institutions that are only incidentally sexist. That means those same institutions could become less so with the right adjustments, like more draconian sentencing for crimes against women, or more female judges.

But the prison system is racist and brutal by design, not by accident or mismanagement, just as the court system regularly fails the most vulnerable because it was built to protect the powerful. “The challenge of the 21st century is not to demand equal opportunity to participate in the machinery of oppression,” revolutionary thinker Angela Davis has written. “Rather, it is to identify and dismantle those structures.” Yet leveraging our existing legal system for criminalization remains the go-to strategy for most feminists when it comes to dealing with objectionable behavior. Criminalization entails fines and incarceration; it does not meaningfully concern itself with rehabilitation, education, victim care, or prevention. Its ability to deter other potential offenders is unproven—or, arguably, proven to be nonexistent, as is especially demonstrable with laws against drug use and possession—and the recidivism rate is astronomical. Moreover, the legal system is not accessible to everyone. Undocumented people cannot use it. People leading already criminalized lives, like sex workers, often cannot use it, and marginalized people are also discouraged from or outright prevented from using it by a slew of means. (The most obvious of which is usually time and money.)

This instinct to turn to the state is not unfamiliar to me. I, too, learned from a young age that laws and courts and police are the way to deal with almost everything: You notice something is wrong, you get a law passed or use an existing law to stop it, and the problem is solved. This is not how our current laws work in practice, and it is incumbent upon us to face that fact with honesty and creativity. When activists speak out against police and prisons, people immediately demand that they offer a replacement apparatus, but it is an impossible demand. The transformation needs to be more profound than a simple swap. Prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba speaks on this point with great eloquence: “We have to transform the relationships we have with each other so we can really create new forms of safety and justice in our communities. [The work of abolition] insists that it is necessary that you change everything.” [emphasis added.]

Many feminists, though, have lost their foremother’s radical vision of changing everything. Instead, they are ready to work within the tight confines of an ineffective system, and they endorse and invest in a de facto police state. The “feminist” modifier itself is useless for indicating a stance on this issue, as it is for many others: protecting the rights of trans women, for instance, or even the legality of abortion.

This tension is long-standing and perhaps inevitable given that feminism is assumed to galvanize people under a banner of gender rather than shared ideological and moral commitments, as a formal organization, like a political party or a local activist group, would. There’s no explicit platform for feminism because it’s an idea, ownerless and atomized, based on the observation of one specific, persistent source of imbalance in a stunningly unfair world. It can be invoked (cynically or sincerely) by anyone, which is part of why it’s been so easily co-opted by corporations who use superficial gestures of pro-women sentiment for brand management, and by a mainstream media that anoints clueless celebrities like Lena Dunham, Taylor Swift, and Amy Schumer as the vanguard of righteous, pro-lady politics.

Aside from for-profit institutions muddying the waters, there’s also the matter of individual dissent. Even groups with clear and detailed mission statements run into internal disagreement. That’s healthy and good. But today’s concept of feminism provides such a wide net that some women (and men) assume gender alone makes one eligible for membership, regardless of actual convictions. “Feminist” has become synonymous with hollow phrases like “female empowerment” and “strong women” and “girl power.” If a woman’s ambition were automatically feminist by virtue of her gender alone, that would hold true whether she’s directing her energies into exploiting workers in other countries, trying to overturn affirmative action, or working to keep her neighborhood free from immigrants.

Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In campaign notoriously exemplifies this sort of self-serving attitude. In her 2010 TED Talk and 2013 book by the same name, Sandberg exhorted working women to throw themselves into the corporate world, implying that women’s general lack of representation in the boardroom was a function of their own timidity and emotionality rather than workplace discrimination or intractable secondary obstacles (like being unable to afford childcare, or simply not wanting to sacrifice quality of life for a title). Why is it important that women assume more prominent roles in corporations? Because their absence indicates sexism, and sexism is bad. Or because they’d bring “diversity,” and diversity makes a company stronger. A number of similar platitudes could be offered in response to this question, but none would be sufficient. By assuming that having more women is better, period, we relinquish the opportunity to question what it is the corporation does (read: who it harms and how it harms them), what’s inherently good about climbing to the top of any hierarchy, or how it socially benefits all women for one particular woman to earn an obscene amount of money.

The feminism espoused by Sandberg goes by many names—neoliberal feminism, white feminism, corporate feminism—but whatever it’s called, its priority is to help a small number of people further consolidate power and money without rocking the proverbial boat. Few systems are threatened by slotting women into roles traditionally held by men, because absolute wealth and absolute power tend to corrupt absolutely. Few want to dismantle the means by which they achieve tremendous success; rather, they want to further consolidate that success in all its forms: influence, wealth, and so on. If patriarchy’s worst offense were keeping women out of the workplace, then sure, women like Sheryl Sandberg would be triumphs of the cause. But the notion that women shouldn’t work outside the home was always unique to the white upper and middle classes. Poorer women never had the option to stay at home, and Black women in the United States have virtually always been expected to work, if not in the fields then in white homes as “domestic” servants. The far more noxious effects of patriarchy, like rendering women incapable of exercising autonomy over their reproduction or paying them lower wages for their work, can and do endure even with more women “on top.” You never have to look very far to find female politicians voting to make abortion less accessible, or female activists trying to take down Planned Parenthood, just as you don’t have to search very hard to find powerful women who explicitly blame other women for their own sexual assault or who, à la Ann Coulter, go so far as to suggest women shouldn’t have the right to vote.

So not only is Lean In feminism useless for achieving a truly pro-women future wherein all women see their lives improved, but it actively undermines that vision. It’s a feminism that purports to push for progress while wedding itself to the perpetuation and justification of patriarchy’s equally insidious attendants: capitalism, imperialism, racism, ableism, and so on. Every other hierarchy may remain intact as long as (some) women are allowed a shot at approaching the top. By participating in unjust power structures, and giving those same structures a fresh patina of legitimacy, this feminism places a radically reimagined future further out of reach for the people—women and men alike—who so desperately need it.

“There’s no explicit platform for feminism because it’s an idea, ownerless and atomized, based on the observation of one specific, persistent source of imbalance in a stunningly unfair world. It can be invoked (cynically or sincerely) by anyone, which is part of why it’s been so easily co-opted by corporations who use superficial gestures of pro-women sentiment for brand management”

Ignoring the problems of less advantaged women to secure the rights, and later, the high-profile achievement, of the privileged has been part of feminism’s legacy since the beginning. Suffragettes (who were primarily white and middle or upper class) were often outspoken racists who fomented anti-Black sentiment, participating in segregation and endorsing colonialism. Various white figureheads of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s were willfully ignorant about and explicitly unconcerned by the social concerns shared by women of color; they also disavowed lesbians and tried to keep them apart from the larger movement. Today, many prominent British feminists stoke anti-trans fears among their followers and rally for further criminalization and stigmatization of sex work—in spite of the fact that doing so demonstrably keeps female (and male, and non-gender-conforming) sex workers extraordinarily vulnerable. American feminists are quieter on these issues, but then, they’re quiet on a lot of issues—namely, almost anything that doesn’t revolve around (white, cis) women’s reproductive options and (white, cis) women’s experience of sexual assault or harassment, or cultural representation as measured by women directing big-budget films and winning awards.

Mainstream feminism fails us because, by definition, it adheres to the status quo and nudges it only slightly to the left, if at all. It wouldn’t be mainstream if it didn’t play by these rules. But the status quo is actively harmful to almost everyone, regardless of gender. It concentrates wealth in the hands of the .01 percent (US’ 3 RICHEST MEN HAVE MORE WEALTH THAN HALF OF THE POPULATION was a repeated headline in late 2017 following the release of a report by the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C.) It keeps many of us underemployed and terrified of getting sick, lest we need medical care that far outstrips our resources. It allows police officers to murder with impunity. It renders voting inaccessible to huge swaths of the adult population. It ravages communities with gun violence. It breaks our hearts, and it makes it harder to start every day with enough hope to work for something better.

Perhaps the most apt name for this kind of feminism, then, is sabotage feminism. It exists to stymie the efforts of the most radical feminist values—those that put the most disadvantaged among us first, not last—by turning the very idea of feminism on itself, by feeding feminism its own tail. Second-wave feminists—those active in the late 1960s through the ’80s—envisioned a profound remaking of society on sexual, familial, and economic levels. These years birthed the dreams of wages for housework, the Equal Rights Amendment, and unapologetic abortion on demand, and it offered women a fantasy of solidarity as they rallied behind those efforts. But whatever wave of feminism we’re experiencing now might be best described as no wave, for it leaves us bereft of unity, momentum, and power as we compete against each other to sit with men on the boards of companies with track records of unremitting mendacity.

I know a lot of feminists are more progressive and intelligent than what the largest news outlets suggest. When I use “us” and “we,” it’s with this reality in mind; it is an attempt to encompass people of any gender who desire less suffering for all, and who believe their own freedom, comfort, and pleasure should not come at the expense of someone else’s. But because Lean In feminism—the feminism that says any conventionally successful woman is likely to be an example of feminist success—still has a near-monopoly when it comes to the dominant public discourse, excoriating and disavowing it is an important step in pushing against the ways it’s leveraged to silence more substantive concerns.

I’m not ready to abandon feminism, because misogyny and sexism are real. But I’m disheartened by the derelict quality of what my generation inherited and helped build, or at least permitted to be built on our watch. I believe feminism is both necessary and (in its current state) regularly superfluous—both urgent and too often a distraction. Nothing illustrated this dynamic more horribly than the campaign and election of Donald Trump, a man who bragged about sexual assault, spent decades publicly insulting women in the most reductive ways possible, and has a history of dramatic and crude sexist behavior when it comes to his marriages and his involvement in beauty pageants. He is a vile and enthusiastic chauvinist—there’s no lack of confirmation there—but for all the public hand-wringing over his well-documented misogyny, his worst acts as president have hardly been confined to the “pussy grabbing” that became the central rallying cry against him as the election approached in late 2016. As far as we know, he’s not leveraged his office to sexually harass or assault anyone; with a few notable exceptions, he’s not even spent much time verbally attacking specific female enemies on Twitter. It doesn’t seem he’s opposed to women in high places earning lots of money and making big decisions, and he has a number of women in top positions within his White House staff and cabinet—which, as I’ve mentioned, is entirely consistent with the Lean In era’s definition of feminist progress.

What he’s done instead is incite his followers—and I say “followers” not only to reflect the parlance of social media but because it seems the most accurate word to describe his fervent fans—and the authority figures among them to enact a wide range of brutal aggression against Muslims, Mexicans, transgender people, the lower classes (meaning anyone outside his own tax bracket), and anyone from protesters to journalists who oppose or irritate the ruling class. Listing some of his recent offenses feels both futile and necessary as his atrocities continue to amass, only to be wiped away by each new headline. At the time of this writing, he’s held rallies to further agitate for white supremacy, defended the neo-Nazis who terrorized Charlottesville, Virginia, in mid-August 2017, and laid blame for “violence” at the feet of leftists who protected peaceful clergy members. He is, at least superficially, trying to follow through on his promises to build a wall between the United States and Mexico. The Supreme Court has allowed his infamous Muslim travel ban to take full effect. Despite the vast unpopularity of such a decision, his administration has managed to overturn net neutrality and pass a heinous (and again, hugely unpopular) tax bill.

All of which is to say that rather than attacking women as a discrete group, Trump has followed in the footsteps of the presidents before him (yes, even the Democrats) and instead focused on waging war both at home and abroad against people of color, the poor, our natural environment, and tools of active political participation (like the right to vote and to protest). Again, women are impacted by all of this, because many women are poor, most women are not white, and all women, like all humans and indeed all mammals, need a hospitable environment in which to live. But feminism without intersectionality—in other words, without sensitivity and equal attention to other nexuses of discrimination and oppression, such as race and sexuality—is worthless. And the feminism on tap in this moment is emphatically not intersectional.

Misogyny is alive and thriving, and we cannot tolerate a world in which this is so. Yet we also know misogyny is rarely the dominant motivation behind the most destructive work of politicians, corporate leaders, and other multimillionaires or billionaires not already among those two groups. They operate under other more immediate and selfish concerns, like how to crush challenges to their outsize power, further inflate their bloated wealth, and deflect responsibility for all the misery they inflict. With its gender-based wage asymmetries and its outsourcing of reproductive labor (the unpaid work of bearing and raising children) to primarily women, sexism is useful, but rarely the end goal in and of itself. Sabotage feminism, the feminism that’s visible to most Americans and to most women, that’s espoused by both celebrities and op-ed columnists, has trouble grappling with this. It can say plenty about how Trump habitually demeans women, but it hasn’t developed the sort of trenchant, comprehensive critique that would allow it to speak meaningfully on the racist and fascist legacy he has adopted so completely, one in which the state is entitled to any and all of our personal data; to carry out massive attacks overseas with heavy civilian casualties in countries with which we’re not even officially at war; to cage its own citizens before they’re found guilty of any crime and then indefinitely thereafter; to violently aggress against peaceful protesters and to murder citizens with impunity through an unrestrained and anti-Black police force.

“Feminism without intersectionality—in other words, without sensitivity and equal attention to other nexuses of discrimination and oppression, such as race and sexuality—is worthless. And the feminism on tap in this moment is emphatically not intersectional.”

As many have pointed out since November 2016, none of what Trump advocates is new. He is unusually offensive to middle- and upper-class propriety, but it is only the bluntness of his rhetoric that’s unique to him, not its content. His continued support from the Republican Party, and the limpness of elected Democrats’ response, speaks to just how entrenched his beliefs are. How can we concern ourselves with unreasonable beauty standards when families are being ripped apart by deportation? How can we harp about a wage gap when even men aren’t earning enough to live?

But of course, those are false dilemmas. There should be nothing incompatible about feminism and any other movement for social justice; on the contrary, true feminism should be essential to the success of all other progressive movements. Conflict materializes when we buy into the notion that feminism is a narrow aperture through which to consider our world, one that can only inform our analysis on issues that break down neatly around gender. When feminism is treated as if it can respond solely to oppressions that move neatly from men to women—with no complicating factors or contextual ambiguity—it becomes the agent of our enemies, lending itself to the adoption of a victim mindset in which all women are threatened by all men and where other vectors of power, like race or able-bodiedness or wealth, are immaterial. It conveniently obfuscates just how easily women can participate in oppression of other women, and of men, too—and always have.

“When feminism is treated as if it can respond solely to oppressions that move neatly from men to women—with no complicating factors or contextual ambiguity—it becomes the agent of our enemies, lending itself to the adoption of a victim mindset in which all women are threatened by all men and where other vectors of power, like race or able-bodiedness or wealth, are immaterial.”

If feminism were a vehicle of rescue or even just improvement for individual women, as opposed to being a radical vision with the power to remake society on a grand scale, it would still have to intervene in health care, in childcare, in gun control. It would have to grapple with exploitative workplaces, and with incarceration, and environmental degradation, because women’s lives are deeply degraded by and even lost to these conditions. Feminism should expand our commitment to each other as human beings, not contract it by replicating the same power structures we should be decisively overthrowing. And the good news is: It can. Just as we expect men to speak out around other men who evince sexist or misogynist attitudes, so should we commit ourselves to confronting and educating women (or anyone) who depict feminism as a strategy of personal betterment by any means necessary instead of a political cause organized around the goal of a more just world. We have to hold ourselves to high standards and invite those around us to join.

*

I’m not sure if I’m a “feminist” or not. Some hateful people have identified as feminists over the years, and while I’m loath to ally myself with them, I’m equally loath to cede the word without a fight. But it’s not a name I need to call myself anymore, perhaps, because its tenets feel sufficiently absorbed into the gestalt of who I am. Plus, the neurotic insistence on labeling things “feminist”—not just ourselves and each other, but personal products and companies and movies and ad campaigns—feels like part and parcel of a diminishing of what the word could mean. Feminism itself is a practice, a tool, a weapon, an insight. It is the truth that in our current world, women are often intentionally, systematically disadvantaged and exploited because of their gender. Therefore, “feminist” should be regarded as a promise, a mode of being, a commitment carried into all our efforts to recognize and reject sexism, and to let that inform our rejection of all types of injustice. Never again should it be treated as a static label that anyone can put on or take off like a piece of statement jewelry.

The current condition of feminism is not the permanent condition of feminism. Though there are some (sadly, many) people who work to make it an ideology that doesn’t recognize or incorporate the specific rights and needs of trans women, sex workers, Black women, disabled women, and poor women—among others—feminism itself has no gatekeepers. It is not a club from which others can exclude you. No one can keep you from living in concert with its core realizations, and what you call yourself while you act from that foundation ultimately means very little. Coherent, ethical feminism is available to anyone who recognizes that gender is relevant only inasmuch as a society makes it so; that gender alone determines nothing about a person’s worth, aptitude, intelligence, or character; and that policies and laws and rhetoric to the contrary are not only unjust and harmful, they are incorrect and born from self-serving biases.

To make feminism work for where we are now, I propose we break it open. Let our vision be confined not to one wave but to an entire sea. I want a flexible feminism that floods into every other cause we adopt, that girds every framework we erect, as so many abolitionist and socialist and anarchist women before us proved it can. Because we need feminism still, no matter how badly it disappoints us in its most visible form. We will probably need it forever; its work will never be complete. It’s because it is so indispensable to any and every convincing vision of a better world that we must continue to demand feminism itself be better, no matter what word we rally around.

__________________________________

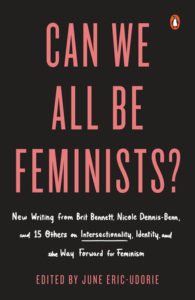

From Can We All Be Feminists?. Edited by June Eric-Udorie. Courtesy of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2018 by Charlotte Shane.

Charlotte Shane

Charlotte Shane is a nonfiction author and essayist. Her two books are Prostitute Laundry and N.B.. Additionally, Charlotte's writing has appeared in The New Inquiry, Adult Mag, Brooklyn Magazine, Hazlitt, Jezebel, and The Hairpin, among other outlets.