How Do We Move Beyond Commodified Feminism?

Charlotte Shane on the Dangers of Going Mainstream

I’m not ready to abandon feminism, because misogyny and sexism are real. But I’m disheartened by the derelict quality of what my generation inherited and helped build, or at least permitted to be built on our watch. I believe feminism is both necessary and (in its current state) regularly superfluous—both urgent and too often a distraction. Nothing illustrated this dynamic more horribly than the campaign and election of Donald Trump, a man who bragged about sexual assault, spent decades publicly insulting women in the most reductive ways possible, and has a history of dramatic and crude sexist behavior when it comes to his marriages and his involvement in beauty pageants. He is a vile and enthusiastic chauvinist—there’s no lack of confirmation there—but for all the public hand-wringing over his well-documented misogyny, his worst acts as president have hardly been confined to the “pussy grabbing” that became the central rallying cry against him as the election approached in late 2016. As far as we know, he’s not leveraged his office to sexually harass or assault anyone; with a few notable exceptions, he’s not even spent much time verbally attacking specific female enemies on Twitter. It doesn’t seem he’s opposed to women in high places earning lots of money and making big decisions, and he has a number of women in top positions within his White House staff and cabinet—which, as I’ve mentioned, is entirely consistent with the Lean In era’s definition of feminist progress.

What he’s done instead is incite his followers—and I say “followers” not only to reflect the parlance of social media but because it seems the most accurate word to describe his fervent fans—and the authority figures among them to enact a wide range of brutal aggression against Muslims, Mexicans, transgender people, the lower classes (meaning anyone outside his own tax bracket), and anyone from protesters to journalists who oppose or irritate the ruling class. Listing some of his recent offenses feels both futile and necessary as his atrocities continue to amass, only to be wiped away by each new headline. At the time of this writing, he’s held rallies to further agitate for white supremacy, defended the neo-Nazis who terrorized Charlottesville, Virginia, in mid-August 2017, and laid blame for “violence” at the feet of leftists who protected peaceful clergy members. He is, at least superficially, trying to follow through on his promises to build a wall between the United States and Mexico. The Supreme Court has allowed his infamous Muslim travel ban to take full effect. Despite the vast unpopularity of such a decision, his administration has managed to overturn net neutrality and pass a heinous (and again, hugely unpopular) tax bill.

All of which is to say that rather than attacking women as a discrete group, Trump has followed in the footsteps of the presidents before him (yes, even the Democrats) and instead focused on waging war both at home and abroad against people of color, the poor, our natural environment, and tools of active political participation (like the right to vote and to protest). Again, women are impacted by all of this, because many women are poor, most women are not white, and all women, like all humans and indeed all mammals, need a hospitable environment in which to live. But feminism without intersectionality—in other words, without sensitivity and equal attention to other nexuses of discrimination and oppression, such as race and sexuality—is worthless. And the feminism on tap in this moment is emphatically not intersectional.

Misogyny is alive and thriving, and we cannot tolerate a world in which this is so. Yet we also know misogyny is rarely the dominant motivation behind the most destructive work of politicians, corporate leaders, and other multimillionaires or billionaires not already among those two groups. They operate under other more immediate and selfish concerns, like how to crush challenges to their outsize power, further inflate their bloated wealth, and deflect responsibility for all the misery they inflict. With its gender-based wage asymmetries and its outsourcing of reproductive labor (the unpaid work of bearing and raising children) to primarily women, sexism is useful, but rarely the end goal in and of itself. Sabotage feminism, the feminism that’s visible to most Americans and to most women, that’s espoused by both celebrities and op-ed columnists, has trouble grappling with this. It can say plenty about how Trump habitually demeans women, but it hasn’t developed the sort of trenchant, comprehensive critique that would allow it to speak meaningfully on the racist and fascist legacy he has adopted so completely, one in which the state is entitled to any and all of our personal data; to carry out massive attacks overseas with heavy civilian casualties in countries with which we’re not even officially at war; to cage its own citizens before they’re found guilty of any crime and then indefinitely thereafter; to violently aggress against peaceful protesters and to murder citizens with impunity through an unrestrained and anti-Black police force.

“Feminism without intersectionality—in other words, without sensitivity and equal attention to other nexuses of discrimination and oppression, such as race and sexuality—is worthless. And the feminism on tap in this moment is emphatically not intersectional.”

As many have pointed out since November 2016, none of what Trump advocates is new. He is unusually offensive to middle- and upper-class propriety, but it is only the bluntness of his rhetoric that’s unique to him, not its content. His continued support from the Republican Party, and the limpness of elected Democrats’ response, speaks to just how entrenched his beliefs are. How can we concern ourselves with unreasonable beauty standards when families are being ripped apart by deportation? How can we harp about a wage gap when even men aren’t earning enough to live?

But of course, those are false dilemmas. There should be nothing incompatible about feminism and any other movement for social justice; on the contrary, true feminism should be essential to the success of all other progressive movements. Conflict materializes when we buy into the notion that feminism is a narrow aperture through which to consider our world, one that can only inform our analysis on issues that break down neatly around gender. When feminism is treated as if it can respond solely to oppressions that move neatly from men to women—with no complicating factors or contextual ambiguity—it becomes the agent of our enemies, lending itself to the adoption of a victim mindset in which all women are threatened by all men and where other vectors of power, like race or able-bodiedness or wealth, are immaterial. It conveniently obfuscates just how easily women can participate in oppression of other women, and of men, too—and always have.

“When feminism is treated as if it can respond solely to oppressions that move neatly from men to women—with no complicating factors or contextual ambiguity—it becomes the agent of our enemies, lending itself to the adoption of a victim mindset in which all women are threatened by all men and where other vectors of power, like race or able-bodiedness or wealth, are immaterial.”

If feminism were a vehicle of rescue or even just improvement for individual women, as opposed to being a radical vision with the power to remake society on a grand scale, it would still have to intervene in health care, in childcare, in gun control. It would have to grapple with exploitative workplaces, and with incarceration, and environmental degradation, because women’s lives are deeply degraded by and even lost to these conditions. Feminism should expand our commitment to each other as human beings, not contract it by replicating the same power structures we should be decisively overthrowing. And the good news is: It can. Just as we expect men to speak out around other men who evince sexist or misogynist attitudes, so should we commit ourselves to confronting and educating women (or anyone) who depict feminism as a strategy of personal betterment by any means necessary instead of a political cause organized around the goal of a more just world. We have to hold ourselves to high standards and invite those around us to join.

*

I’m not sure if I’m a “feminist” or not. Some hateful people have identified as feminists over the years, and while I’m loath to ally myself with them, I’m equally loath to cede the word without a fight. But it’s not a name I need to call myself anymore, perhaps, because its tenets feel sufficiently absorbed into the gestalt of who I am. Plus, the neurotic insistence on labeling things “feminist”—not just ourselves and each other, but personal products and companies and movies and ad campaigns—feels like part and parcel of a diminishing of what the word could mean. Feminism itself is a practice, a tool, a weapon, an insight. It is the truth that in our current world, women are often intentionally, systematically disadvantaged and exploited because of their gender. Therefore, “feminist” should be regarded as a promise, a mode of being, a commitment carried into all our efforts to recognize and reject sexism, and to let that inform our rejection of all types of injustice. Never again should it be treated as a static label that anyone can put on or take off like a piece of statement jewelry.

The current condition of feminism is not the permanent condition of feminism. Though there are some (sadly, many) people who work to make it an ideology that doesn’t recognize or incorporate the specific rights and needs of trans women, sex workers, Black women, disabled women, and poor women—among others—feminism itself has no gatekeepers. It is not a club from which others can exclude you. No one can keep you from living in concert with its core realizations, and what you call yourself while you act from that foundation ultimately means very little. Coherent, ethical feminism is available to anyone who recognizes that gender is relevant only inasmuch as a society makes it so; that gender alone determines nothing about a person’s worth, aptitude, intelligence, or character; and that policies and laws and rhetoric to the contrary are not only unjust and harmful, they are incorrect and born from self-serving biases.

To make feminism work for where we are now, I propose we break it open. Let our vision be confined not to one wave but to an entire sea. I want a flexible feminism that floods into every other cause we adopt, that girds every framework we erect, as so many abolitionist and socialist and anarchist women before us proved it can. Because we need feminism still, no matter how badly it disappoints us in its most visible form. We will probably need it forever; its work will never be complete. It’s because it is so indispensable to any and every convincing vision of a better world that we must continue to demand feminism itself be better, no matter what word we rally around.

__________________________________

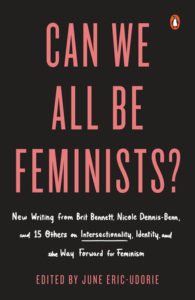

From Can We All Be Feminists?. Edited by June Eric-Udorie. Courtesy of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2018 by Charlotte Shane.

Charlotte Shane

Charlotte Shane is a nonfiction author and essayist. Her two books are Prostitute Laundry and N.B.. Additionally, Charlotte's writing has appeared in The New Inquiry, Adult Mag, Brooklyn Magazine, Hazlitt, Jezebel, and The Hairpin, among other outlets.