How Do Celebrity Conspiracy Theorists Become Who They Are?

Tea Krulos on Richard McCaslin and the Origins of Alex Jones

Richard McCaslin moved to Austin in 2000. His main motivating factor was to reconnect with his delivery driver friend Terrance from Houston. Richard needed a creative project to balance the negative news he had been receiving. This film project, Crackdown and Jumping Jack, could have been just what he needed. Crackdown, to be played by Richard, would be a goggle-sporting, stop-sign-shield-wielding superhero. His trusty backup would be Terrance as Jumping Jack, a jack-o’-lantern-masked sidekick.

While he was shuttling around Ohio, Florida, California, and Texas, Richard was consistently working on the script, costumes, and other details. He got so into the Crackdown persona that he cruised on a few car patrols in Zanesville dressed as the character, “but nothing happened,” he admits.

As time went on, Richard discovered his enthusiasm for the project wasn’t shared by his partner.

“This Austin period was bad,” Richard sums up. “Terrance had made several promises to help with movie production but once I got down there, he broke every one of them. Terrance told me that he had some friends with some video equipment that we could use. It never happened. He said he knew some people we could cast in the movie. They never showed up. I tried to teach him in stage combat and tumbling, but he had no talent for it. I couldn’t afford to rent (let alone buy) the necessary video equipment and I didn’t really know how to use it anyway. Terrance never offered to pay for anything. The project died and so did our friendship. Austin is a nice town to live in. It’s just that most of my personal experiences at that time were bad.”

Despite his previous vow to not return, Richard took another shot at Hollywood. He auditioned for a role as an FBI agent in the Sandra Bullock comedy Miss Congeniality (2000) but didn’t get the part. He was also paid to spend a day on the set of Spy Kids (2001) to act as one of the monstrous henchmen known as Floop’s Floogies. The scenes were later cut and recast.

“The extras were never actually used. The union stuntmen just filled the henchmen roles. We still got paid for the day.” Richard says the extras mostly hung out with cult horror makeup and special effects artist (and actor) Tom Savini, who worked on the production, playing cards. Back in Austin, Richard found a job as a host and cashier at Owens Family Restaurant on I-35, the last payroll job he’d have for many years.

During this period of drifting, Richard’s mother died. It was absolutely devastating to him. His parents’ estate left him a sizable inheritance—about $675,000. But with both parents deceased, no siblings, and a recently soured friendship with his creative partner, Terrance, Richard had something thatmoney couldn’t remedy—loneliness.

In Austin, Richard found something to fill that void.

*

Alex Jones was raised in Rockwall, Texas, the son of a dentist and a homemaker. In a Rolling Stone interview, he says his first experience with authority being deceptive and hypocritical was in high school, where he’d witnessed off-duty Rockwall cops dealing drugs at parties. These were the same cops that did D.A.R.E. anti-drug presentations at school and drug-tested Jones and his football teammates.

After his family moved to Austin, Jones took an interest in reading history. A major influence he found on his father’s bookshelf was a 1971 book titled None Dare Call It Conspiracy by Gary Allen, a book that lays out the blueprint to the New World Order.

After high school, Jones attended community college in Austin and landed a job at radio station KJFK in 1996, where he hosted The Final Edition. He was fired in 1999, he says, for talking too much about “inside-terror-job stuff.” But by then he had already realized and harnessed the power of the Internet to broadcast online and syndicate The Alex Jones Show to several other stations by himself.

One of the first well-known Alex Jones meltdowns was during his broadcasts leading up to New Year’s Eve, 1999.

Jones called his new website platform InfoWars, and his strong online presence in the early days of the Internet is how he has consistently stayed ahead in younger demographics. His online reach gives him a wider audience than talk rivals like Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck and would eventually build InfoWars into a multimillion-dollarplatform.

The Internet is also where he quickly developed a new nickname in forums, “Alex Fucking Jones”—“fucking” being such a versatile word that the nickname could describe awe, disdain, disbelief, or sometimes all of the above, depending on who was using it and in what context. “I’ll pay good money if an actual living, breathing person who works at Twitter can seriously e-mail me and explain why my accounts were deemed more dangerous than Alex Fucking Jones,” a writer at SomethingAwful.com posted after his account was banned as “hateful content” after joking about Nancy Pelosi eating children.

In the mid-1990s, Jones went to Austin Community College and began filling in for shows on cable access station Austin Community Television (AC-TV), which lived up to the city’s unofficial motto “Keep Austin Weird.”

The cable access station would be where he would first air his documentary projects. His first film, America: Destroyed by Design, was released in 1997 and focused on globalism and the Oklahoma City bombing, which Jones says was a false flag attack designed to look like the work of terrorists but perpetrated by our own government.

One of the first well-known Jones meltdowns was during his broadcasts leading up to New Year’s Eve, 1999. Half-crazed with Y2K bug fever, Jones ranted about the impending apocalypse that was approaching the midnight hour. Jones reported that hundreds of thousands were dead in Chechnya, nuclear plants were melting down in Pennsylvania, world economies were collapsing, store shelves were empty and gas stations out of fuel, a police state was getting ready to mobilize, and other alarming catastrophes were happening around the world, all of it orchestrated by Vladimir Putin, Jones told his listeners.

“It is absolutely out of control, it is pandemic, ladies and gentlemen!” Jones said. It was exciting radio, but none of it was true.

In the year 2000 Jones created five documentaries, including America: Wake Up or Waco (which documented his efforts to help rebuild the Branch Davidian church as a memorial to those that died there in the standoff with the ATF and FBI), and Police State 2000, which “exposes the militarization of American law enforcement and the growing relationship between the military and the police.”

But his most sensational documentary that year was titled Dark Secrets: Inside Bohemian Grove. The brazen trespass into the Grove, a private retreat site in northern California known for hosting some of the world’s most prominent men, was an early boost to his cred as a conspiracy “Infowarrior,” as Jones calls his loyal listeners.

In July 2000, Jones and cameraman Mike Hanson crawled through the woods and boarded a shuttle truck in the Grove’s parking lot. Hanson was carrying a duffel bag with a camera hidden inside. Once they got in, they nervously wandered around, trying to act discreet, saying they were guests of the Texas-heavy Hill Billies camp when questioned by suspicious guards. They recorded the Cremation of Care ceremony in its entirety. The shaky, motion-sickness-inducing footage was cut together

for Dark Secrets, which was broadcast on cable access and sold as a DVD and VHS.

The second party infiltrating that night was author Jon Ronson, who was documenting various conspiracy theorists and extremists, including Jones. After Jones flaked on him, Ronson sneaked in with a local informant by simply looking confident and walking in through the front gate. He recalled the experience in his book Them: Adventures with Extremists.

“My lasting impression was of an all-pervading sense of immaturity,” Ronson writes. “The Elvis impersonators, the pseudo-pagan spooky rituals, the heavy drinking. These people might have reached the apex of their professions, but emotionally they seemed trapped in their college years.”

Alex Jones’ take on the Bohemian Grove is different from all of this. He says there is something more sinister going on there, like satanic rituals. He says the Great Owl of Bohemia represents the false deity Moloch, and that Dull Care represents a child being sacrificed as an offering to appease this ancient evil.

The Dark Secrets documentary opens with some dramatic, monster-stalking-you-in-the-woods music, mixed with images of the Cremation of Care ceremony. Alex Jones then appears and warns viewers about the shocking footage they will see.

“Could it be when you have all the power and all the women and all the land and all the art that you have to do something new—you have to go against the basic grain of humanity, you have to get off in a sick way?” Jones asks the viewer, using one of his favorite hooks—the speculative, rhetorical question. He then documents his trip to Monte Rio, California and his analysis of the footage shot from the duffel-bag-hidden camera inside the Grove. Jones describes the Cremation of Care ceremony as a “bizarre ancient Canaanite Luciferian Babylon mystery religion ceremony.”

“Upon further research of the ritual you just witnessed, it becomes clear it is a mixture of the Babylon cult of Moloch fused with Druidic rites… mixed with Masonic rites from Scotland,” Jones explains. He speculates that artwork on a Cremation of Care ceremony program, when blown up life-size, shows that a skull in the art is the “anatomical size of a baby or small child.” He makes the claim again later, saying that the effigy could represent a child, “…or it could be real, ladies and gentlemen!”

As a conspiracy-minded Christian . . . Richard McCaslin’s thinking was shaped by a wave of paranoia known as the Satanic Panic.

Jones’ own footage sinks this “child effigy” claim. The effigy, Dull Care, speaks to the Bohemians during the Cremation of Care ceremony, not with the voice of a child, but a sinister booming baritone of an adult. And is it realistic to expect that program cover art is going to have an anatomically correct skull on it?

Other conspiracy theorists have elaborated and added their own flourishes to the story. There is an underground chamber, they say, where sex slaves are kept shackled to the walls. There are claims that snuff films had been recorded in the Grove, and others have run with Jones’ speculation that the Cremation of Care was just one of several ceremonies where actual people, even children, and not wooden effigies are being sacrificed at the altar of the bloodthirsty Moloch. Some have even said that an evil breed of aliens, the Reptilians, congregate there to plot their eventual world domination.

*

“I had heard the term ‘conspiracy theory’ but mostly in a Bigfoot, UFO, and aliens connotation,” Richard told me. “I already knew the government lied about a lot of things (Vietnam, Watergate, etc.) but I didn’t know there was a ‘community’ of like-minded people seeking the truth. Jones was compelling because he was ‘in your face’ about his stories and had actually traveled to several ‘hotspots.’”

Richard, alone in Austin and watching AC-TV, caught a broadcast of Dark Secrets: Inside Bohemian Grove sometime in 2000, and he notes that it “changed his life forever.”

“I had just about given up on the Real Life Superhero thing,” Richard says.“ Patrols rarely produce results. I needed a specific mission. What could be more appropriate than taking down a secret society of Satanists?”

As a conspiracy-minded Christian, who had been a young man in the 1980s and ’90s, Richard’s thinking was shaped by a wave of paranoia known as the Satanic Panic. This episode of our culture was a time where the hand of Satan was seen in games like Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy games, comic books, heavy metal music, and New Age practices. There was a widespread fear of Satanic cults who were said to be all over the country and engaged in rituals that included child sexual abuse, black magick, animal and even human sacrifice.

The Satanic Panic was largely launched by a now-discredited bestselling autobiography from 1980, Michelle Remembers, which details author Michelle Smith allegedly being forced to participate in these rituals. Smith, who wrote thebook with the help of recovered memory from a therapist, recalls one 81-day-long ritual in 1955 that summoned the devil himself. The Satanic Panic was spread further by hoaxes, circulating misinformation, and people looking for attention.

The message of a secret Satanic Army was preached by televangelists and “God’s cartoonist” Jack T. Chick, founder of Chick Publications. “Chick tracts” are small comic strip books distributed by an invisible network of people leaving them in public spaces. Chick began producing them in the 1960s and kept them rolling until he died in 2016 (Chick Publications continues to produce new tracts). Chick promoted the Satanic Panic as a conspiracy cabal of Satanists, the Catholic Church, witches, LGBT, secular teachers, atheists, Muslims, and others, often working together as a coalition of the damned. His targets shifted over the decades from Bewitched to Dungeons & Dragons to Harry Potter, but the Devil was always lurking somewhere.

Although the panic died down in the ’90s, some of the effects lingered long after.

*

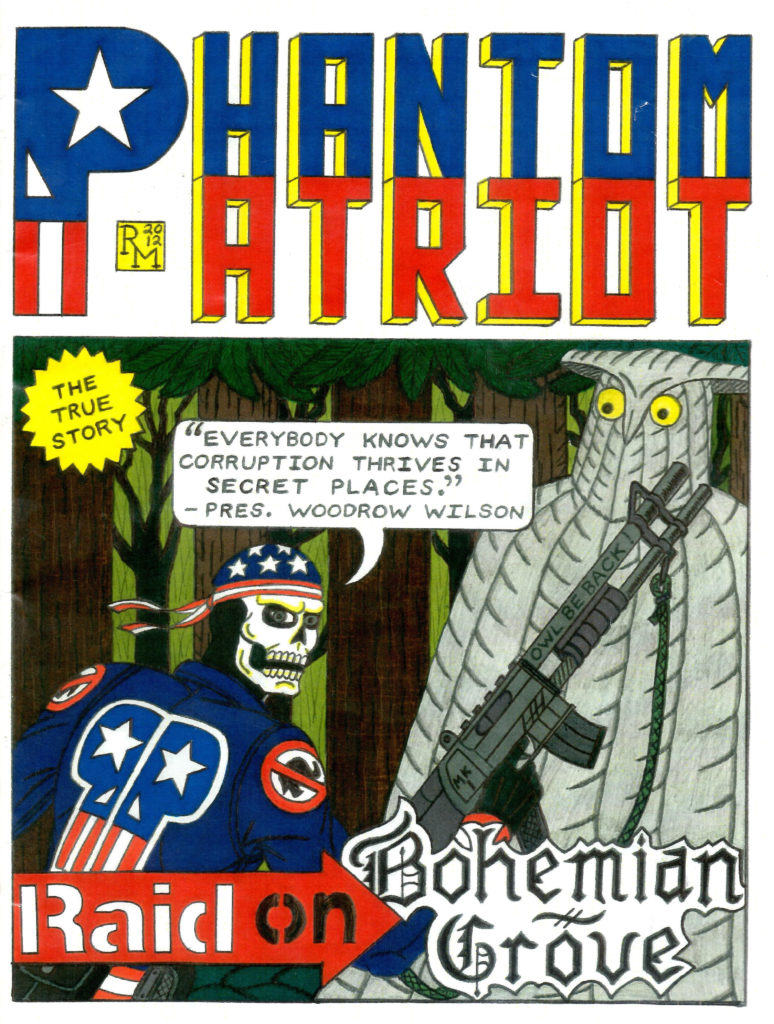

Richard began drafting new superhero ideas on paper in 2000. These were different from his younger creations, because his new heroes now reflected his new mission—to fight the “New World Order.” He created a character called The Activist, who would be a protest character, but Richard dismissed him as “not intimidating enough.” Another idea, the Austin Knight, a potential cable access show host, was scrapped as “too regional.”He continued to sketch until he came up with a new character design he was happy with: the Phantom Patriot.

“I got the skull mask in 1999 from a Halloween store in Cincinnati, Ohio. I used it for a Ghost Rider costume,” says Richard of the most startling aspect of his costume—a grinning skeleton face mask.The rest of the costume consisted of a star-spangled bandanna he wrapped around the top of his head, and a navy-blue jumpsuit. The suit had the words “Phantom Patriot” sewn across the chest and symbols of a donkey and an elephant on his shoulders, each struck out with a red circle and slash. His belt featured the Phantom Patriot symbol as a buckle, a double mirrored letter P. Combat boots rounded out the look.

Richard’s first idea with the persona was to make “symbolic appearances” in costume. He also produced a series of four comic-book-style zines filled with poems and illustrations that took a cue from Alex Jones, condemning the “globalist scum.” His illustrated poems railed against the UN agenda, the mass media, the Federal Reserve, and the deceptive “Uncle Scam.” He listed Infowars.com on each of the pamphlets’ back covers.

Over the course of a few months, Richard printed hundreds of these little zines, distributing them in a similar way to Chick tracts—leaving little piles where people might grab them, and handing them out in person.

Issue number one, a ten-page booklet with a cover date of August 2001, has this poem Richard penned about the Bohemian Grove in it:

Bird in the Bush

Bohemian Grove

What a happening place

Worship the devil

In front of God’s face

Ritual sacrifice

Debauchery and sodomy

Everyone there

Should get a lobotomy

Owl of Babylon

Moloch by name

Stands as an idol

While two Georges bow in shame

As with the father

So with the son

Both believe earth

Should be ruled as one

Richard traveled to the East Coast, making appearances in costume at the Minuteman statue in Concord, Massachusetts, and the Boston Tea Party ship, as well as an appearance in Chappaqua, New York (where the Clintons have a home), leaving his pamphlets as a calling card. He considered visiting the Statue of Liberty, but “I had no idea how the security guards would react to a ‘nutcase in a skull mask,’ so I scrubbed that idea.” He decided to head to Washington, D.C. and the White House instead.

The Phantom Patriot appeared in Crawford, Texas, leaving copies of his zines on the property of President George W. Bush’s ranch.

“I parked my car several blocks from the Capitol Building. I put on my uniform and rode into the National Mall area on a BMX bike. I had a sign on the front that said, ‘Stop the New World Order!’ (subtle) I then proceeded to ride around the whole mall area—the Capitol Building, the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial and the White House. There were plenty of people around. A few laughed and pointed, but most of them just stood and stared at me, slack-jawed. The one notable exception was a little kid. After being prompted by his father, he yells out the window of the car, ‘You’re a freak!’ After circling the White House, I stopped and threw some pamphlets over the fence. There were Secret Service agents sitting in a car in the driveway. I’m not sure if they saw me, but I didn’t hang around to find out.”

After the East Coast, the Phantom Patriot appeared in Crawford, Texas, leaving copies of his zines on the property of President George W. Bush’s ranch and again at a Masonic lodge in Waco, Texas. Part of the goal for these far-spread appearances was, according to Secret Service files, to make it appear as though there was a wide-ranging “Phantom Patriot Movement” distributing literature and cheering the hero on.

Richard felt that distributing literature and making“ symbolic appearances” wasn’t making a deep enough impact. He wanted to engage in a direct action that would transform himself into a bit of folklore, a hero like the Lone Ranger or Batman. He first thought of raiding the Bohemian Grove in 2001. He packed his Phantom Patriot gear into his truck to drive up to the Grove for a “recon mission” during the Midsummer encampment in July of that year, which he described in a letter:

The only maps I had were the regular tourist kind. I got most of my directions from the Alex Jones video. At the end of Jones’ Dark Secrets documentary, he gives instructions on how to drive to the Bohemian Grove… I did a (costumed) recon of the front gate area and parking lot. There were people coming and going, but I didn’t recognize anyone famous. I had my Glock .45 pistol, my Kabar knife and a camera. What I didn’t have was a plan. I didn’t want to risk sneaking in until it got dark (a couple hours later). Even if I did get in, then what?

I wasn’t sure if the sacrifice “victim” for the Cremation of Care was a real baby or not. Even if it was, what should I do; rush in with “guns blazing” and rescue the baby? This was real life, not a comic book. Sure, I could have killed a few satanic pedophiles, but the odds of me getting out of there alive (with a baby in tow) were slim to none.

No matter how it went down, it would be reported in the Illuminati-controlled media as a“terrorist attack against world leaders on vacation!” After mulling this over for a while, I reluctantly packed it in and drove back to Texas to regroup and rethink my mission.

Richard let his Bohemian Grove plans go for the moment.

“At that time, I wasn’t quite ready to get arrested, let alone die for the cause,” Richard wrote to me. “September 11 changed all that.”

__________________________________

Excerpt adapted from American Madness: The Story of the Phantom Patriot and How Conspiracy Theories Hijacked American Consciousness. Used with the permission of the publisher, Feral House. Copyright © 2020 by Tea Krulos.

Tea Krulos

Tea Krulos is a freelance journalist and author from Milwaukee, WI. He writes about local art and entertainment, lifestyle, and food/drink for publications like Milwaukee Magazine, Shepherd Express, and Milwaukee Record. Other publications he’s contributed to include Fortean Times, The Guardian, Boston Phoenix, Scandinavian Traveler, Doctor Who Magazine, and Pop Mythology. He writes a weekly column called “Tea’s Weird Week” on teakrulos.com.