How Did Artists Survive the First Great Depression?

David A. Taylor on Art as Social Intervention

This year the questions come up again with a vengeance: What is the role of artists in a crisis? Writers ask, what does my work mean in this larger emergency? Does my personal creativity matter in the vast public sphere? And most immediately, how do I navigate this meltdown?

When the economy collapsed in 1929, American jobs disappeared at the rate of 20,000 a day. That used to impress people before this pandemic. In the Great Depression, the publishing and arts sectors shrank by about a third, like they have again recently. Creatives were desperate. Then, as now, there was private desperation and there was public desperation.

Harry Hopkins, the New Deal’s jobs program coordinator, focused on the public aspect and short-term solutions. When Congress questioned the idea of supporting artists and writers with jobs in the Works Progress Administration, Hopkins replied that artists had to eat like everyone else. In response to protests in New York by unemployed publishing workers who felt abandoned, the WPA began a small Federal Writers’ Project and others for art, music, and theater. The notion behind “work relief” was that paying work could sustain morale better than direct unemployment payments.

Researching a handful of WPA writers and artists for a book and documentary, I was struck by the variety of their personalities and responses. I found myself examining their choices for clues to getting through our own time. Some were already mature artists, like Zora Neale Hurston, Anzia Yezierska, and Dorothea Lange (who ran a portrait studio in San Francisco for over a decade). Others were fresh out of college like May Swenson, Saul Bellow, and Margaret Walker. Some we may not associate with the 1930s, like Ralph Ellison and Kenneth Rexroth, who for most people remains tied to the Beat poets, though he resented the comparison.

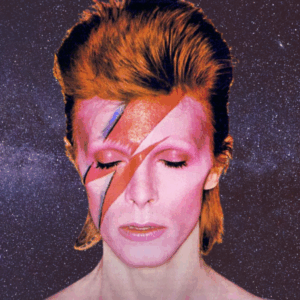

Back then there was even less agreement on a public role for creatives. The Writers’ Project assigned them a public role in producing travel guidebooks, histories, and life stories of everyday Americans, including thousands of narratives of formerly enslaved people. New Deal artists created landscapes, murals, street scenes, portraits, sculptures, and abstracts inspired by American life.

But the process of applying for public arts work had none of the cachet of submitting a proposal to the National Endowment of the Arts (which itself emerged under former New Dealer Lyndon Johnson). The 1930s forerunner had no prestige; its application involved proving you were broke. Nine out of ten WPA writers had to show they had no rent money, no job, and no means.

*

Only once they joined did writers find some sense of community at the program’s offices. “The WPA was a godmother or godfather for so many writers who had had few opportunities before that point,” Maryemma Graham, a distinguished professor at the University of Kansas, told Poets & Writers. “For example, the largest single impact on black writing before the civil rights movement was really the WPA, not the Harlem Renaissance.” Many Harlem Renaissance writers, she explained, “did not continue to write after the 1920s. … Of the WPA writers who were Black, more of them developed substantial careers beyond that period.” Still, less than four percent of WPA writers were Black.

One of those was Margaret Walker, a Jamaican minister’s daughter in Louisiana. Walker, a new graduate of Northwestern, was so young she had to fake her age to meet the Project’s minimum. In Chicago she contributed to folklore interviews and worked alongside Richard Wright and Nelson Algren (also in their twenties). Over the years, they’d have creative and personal differences, but in Chicago they supported each other in the struggle to forge a literary life.

Jacob Lawrence knew he “wanted to tell a story,” he said later, but was daunted by the competitive genius in Harlem’s literary scene.

Walker joined the South Side Writers Group begun by Wright and developed her collection For My People, which won the Yale Young Poets’ Award in 1942. She pursued an academic career, studying at Iowa and later writing novels including Jubilee while teaching at Mississippi State and raising a family. Walker adapted a model of peer feedback from her South Side days and as a professor mentored a generation of younger women of color including Nikki Giovanni and Alice Walker.

Zora Neale Hurston had already published several novels and books of anthropology. Despite the racism she faced, she maneuvered the WPA bureaucracy toward her understanding of folklore and African-American culture. For the Florida WPA guide, she documented local histories like her own hometown of Eatonville and a violent episode against black voters in Ocoee.

But near the end of her 18 months with the agency (after her stint with the Federal Theatre Project), she sent a proposal for a project dear to her heart—a recording tour—to WPA folklore director Benjamin Botkin. She sketched a plan for traveling Florida’s Gulf coast with state-of-the-art equipment (a massive turntable) borrowed from the Library of Congress.

Her team would record vanishing cultural traditions and songs she’d heard in her research. It was a fruitful time for Hurston and inspired Their Eyes Were Watching God and Moses, Man of the Mountain. Hurston’s entrepreneurial creativity notwithstanding, she died in poverty. It was Alice Walker, mentee of Margaret Walker (no relation) who in the 1970s restored Hurston’s grave and revived her legacy.

In visual art, a first federal art program in 1933 cranked out 15,000 works in six months. It reached one-third of the country’s estimated 10,000 unemployed artists and the Federal Art Project reached still further. Jacob Lawrence, who studied at the Harlem Community Art Center with Romare Bearden, was a WPA artist. Lawrence first considered becoming a writer. He knew he “wanted to tell a story,” he said later, but was daunted by the competitive genius in Harlem’s literary scene. So he chose to tell it in paint. He created most of his Migration Series as a 23-year-old living in a Harlem loft.

*

One program innovation came in the realm of folklore, which had long been a nostalgic corner of academia. Benjamin Botkin brought a wider view of American folklore to his role as WPA Folklore Director, one that mixed literary narrative with the vernacular voice and conversation. Botkin infused this view in the instructions for gathering WPA life history interviewers. You see the influence of that experience on young writers from Ellison and Walker to Algren and May Swenson.

Swenson was the eldest of 10 children in an immigrant family in Logan, Utah. Her Swedish parents came to the US as converts to Mormonism. May was the first in her family to attend college, a renegade in a rough-hewn family (I imagine her like Tara Westover). Swenson found freedom in writing. “I write because I can’t talk,” she said. She’d later become one of mid-century America’s leading poets, causing William Stafford to write, “No one today is more deft and lucky in discovering a poem than May Swenson,” and that a poem by her “suddenly opens into something that looms beyond the material.”

Swenson left Utah after college for New York and found work with the Writers’ Project in the folklore unit, recording dozens of life stories from a vanished rural Bronx to department store workers. She honed her observational skills, like in her description of an older interviewee’s body language: “While talking, he moves his plump little hands with agility, and when trying to think of a word that is slow in coming off the tip of his tongue, the thumb and forefinger of his left hand go to his brow; sporadic wrinkles appear in a sharp V over the bridge of his nose.”

Her WPA supervisor praised her work as “100 percent”: smart choice of informant, “witty and vivid descriptions” and “perfect reproduction of informant’s language, mannerisms, humor, odd expressions. The humor and imagination are excellent throughout.” In her first years in the city, Swenson found her footing, piecing together a number of jobs. She faced years of rejection of her poetry, with its unconventional views of sexual identity and gender, before she found champions and publication in the 1950s.

*

Ralph Ellison was barely out of his teens when he got to New York. He left Oklahoma to study music at Tuskegee, then saw his world upended after his mother died. His first nights in Harlem he slept on a park bench, but with poise introduced himself to Harlem’s cultural icons. With help from Wright, he got a WPA paycheck doing life history interviews. Maybe not the most creative task, but it fed him and allowed him to tune his ear.

He developed a method for transcribing speech that avoided demeaning dialect notations. But the interviews especially showed him a larger canvass for the journeys that he and Wright had taken; there was a movement of historic proportions missed by the media and white historians. When Ellison started writing fiction, those voices haunted and infused Invisible Man.

Dorothea Lange and other photographers of the Farm Security Administration had a wide mandate. They weren’t just technicians shooting farm equipment; their mission was to photograph farm productivity and the rural economy, and cover all aspects of life. Director Roy Stryker urged them to capture “the America of how to mine a piece of coal, grow a wheat field or make an apple pie.” He wanted photography that made the viewer feel the reality.

Grounded in portrait photography, Lange brought a focus on character and emotion to the work. Apart from Migrant Mother, she captured the experiences of drought refugees and more—and sparred with Stryker until he fired her. Her sense of social justice advanced in photographing the Japanese American communities she saw displaced.

She applied to work for the War Department, serving like an undercover observer, documenting conditions in the wartime camps. That imagery (see her exhibit at MoMA) would ultimately be filled out by the WPA painter Miné Okubo, whose family was sent to the camps. Okubo’s 1946 book Citizen 13660 anticipated the graphic memoir with an inside view of that experience.

Some WPA guidebooks were censored and denounced by citizens’ committees in their time, and some of the writers’ later works were banned.

The arts provide a fuse for alarmist politicians, and Congressman Martin Dies of Texas lit one in the late 1930s. Dies led the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which had a mandate to investigate home-grown white supremacist terrorists. Instead, he shifted its focus to suspected socialists and communists, and smeared the New Deal arts programs until he managed to get them defunded. One bit of the Writers’ Project that drew Dies’ outrage was an essay by Richard Wright titled “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” in an after-hours anthology. It described frankly the threats and violence black Americans faced every day.

*

In researching 1930s Gotham for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Michael Chabon was moved by the WPA Guide to New York City. Beyond the shadow city of the past described in the guidebook, he was struck by its tone: “Coming out of this absolutely devastating period, there’s this amazing tone of optimism and faith in the common people, the sense that there’s a prevailing, quirky, orderliness to life in New York City,” Chabon told me. The Depression writers captured the city, with its deep divisions, “going about its normal business of being an insane pressure-cooker/volcano/petri dish of commerce and life.”

Then they moved on. Rexroth entered the Depression as a bohemian and emerged from editing the WPA guide in California with an academic career, like Walker. Like many who made it through, he rarely looked back. But in the 1960s he revisited the WPA murals in San Francisco’s Coit Tower that his friend Ralph Stackpole had overseen. He wrote:

For years I remembered them as conveying something of the sensation of waking up with the funny papers over your face. I was amazed to discover that they really are pretty good. They were painted by most of the leading artists of the community, under an emergency program that preceded the WPA and which was designed primarily to get money into circulation, not to accomplish anything. Yet they are a very solid accomplishment indeed.

But public art that presents history can become intensely controversial. Last year another WPA mural in San Francisco—in a school—drew protests for depicting George Washington amid enslaved people and brutalized Native Americans. Last August, after a public comment period and some soul-searching, the school board voted to conceal the murals from view (overruling an earlier vote to paint them over).

Some WPA guidebooks were censored and denounced by citizens’ committees in their time, and some of the writers’ later works were banned. They reflect art’s power in shaping and triggering American identities and norms. Even this year, Invisible Man appeared on an Alaska school board’s list of banned books (along with work by Maya Angelou and others) for mentions of incest, racial slurs, and profanity.

Maybe the WPA let new passions into the public space. “Writing is an act of salvation,” Ellison wrote in a letter to Wright after seeing the Great Migration unspool in Wright’s photo essay, 12 Million Black Voices. “God! It makes you want to write and write and write, or murder.”

David A. Taylor

David A. Taylor is an adjunct professor of science writing at Johns Hopkins University and the author of Cork Wars: Intrigue and Industry in World War II (Johns Hopkins University Press) and Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America (Turner Publishing), now available as an audiobook..