How Dick Gregory Learned to Subvert Racist Audiences

“I went all the way back to childhood.”

It’s 1960. That year I made $1,500 the whole year. I averaged out $30 a week. I went back into Roberts Show Club and stayed a long time this time. I was really proud of myself at Roberts. The first time I had ever invited Lil, Sammy Davis came in with Nipsey Russell. When Nipsey came in, he was the comic and I was just the emcee. When Sammy Davis came in, that’s when I learned one of my greatest lessons in show business. It was the cause of me making it in three years instead of thirty.

Sammy Davis and Nipsey Russell were the biggest attraction that Roberts ever had in his show club. Being that Roberts had to pay me anyway, after he tried to tell me that I was laid off while they were there, I told him he should let me emcee even though Nipsey was the comic. So they found things for me to do while I was waiting, like help seat people.

I guess the whole time Sammy was there he drew a 95 percent white audience. For some of them it was the first time they’d ever been to the South Side. For some it was the first time they’d ever been to the South Side at night. The place seats almost fifteen hundred people and it’s packed, all the way up to the back door. White people are paying something like $50 tips to get a seat close to the front.

Nipsey opened up the show, and he slayed them. I couldn’t believe it. Sammy came on with all of his talents, but you could truly say that Nipsey Russell stole that show. I couldn’t understand why. And when I did learn this lesson, it was the thing that made me hit it in show business.

I called my wife that night, and I said I’m looking at something that’s so strange here. Nipsey Russell is one of the funniest men in show business, and Sammy is the most talented in show business and there’s no comparison. And yet Nipsey is stealing this show.

Well, at the Chez Paree they had what they called AGVA [American Guild of Variety Artists] night. On Monday nights, all of the acts in the AGVA union can go and perform in this big nightclub, and nightclub owners come in and look at the talent. I had gone down many times, not knowing that Black comedians weren’t accepted in white places. The union people kept asking me, “Don’t you dance? Don’t you sing?” They told me the first spot that would be open for a comedian was about a year and a half off. Knowing what they meant by it, I didn’t bother them anymore.

The audience fought me and with their dirty little insulting statements. I would accept it and say something very clever back, to the extent where they broke.

Nipsey went over so well at Roberts they decided to bring him down for AGVA night. I went down, and Nipsey opened up with racial jokes and nobody laughed. He sat there and died, compared to the response of the white people the night before. That was the key to the whole comic problem in America. A white man will come to a Black nightclub and he’s so afraid and so nervous that anything you mention about race, it just knocks him out. The harder he laughs, the more that means, “I’m all right.” But when Nipsey got downtown, where the white man wasn’t in Nipsey’s house but in his own, the white man didn’t want to hear that and he didn’t laugh. That was the difference.

Nipsey overshadowed Sammy Davis at Roberts—a Black club in a Black neighborhood—because this was definitely guilt and fear of this neighborhood. Of the Black waitress that had to wait on him. Of the Black guy at the door who took his money. So when Nipsey mentioned racial things, whitey felt very uncomfortable and he laughed. And he laughed and he laughed. If a white man’s sitting in a Black place and a waitress drops a drink on him, he’ll jump up and say, “Excuse me.” In a white joint, the club might have a lawsuit. So after I figured this out, I knew which way to go and I started working on it.

Then I realized at one point there was going to be an insult. Some white guy in a white club was going to call me “n*****.” Every white person in the club was going to be embarrassed. This created a hell of a problem, because if a white man brings me in his nightclub and I get insulted and customers walk out, they will remember the incident and tie it to that nightclub. Then it actually would be better for this white man to keep me out of his club. I saw the parallel with when I was kicked in the mouth as a little boy shining shoes. If a customer calls me a n***** in a nightclub, the owner is in the same situation as that bartender—losing customers over me.

I started developing a comeback, and for six months, I had Lil yell insults at me. For some reason, I wasn’t getting the answer. A split second of thinking could mean I would lose the whole crowd. Once it happened, people would start feeling sorry for me. And if someone feels sorry for me, I can’t make them laugh after I recover. Comedy is no more than disappointment with a friendly relation. A man cannot have relations toward another man when he feels sorry for him. An example: If you give money to a blind person, you don’t have a friendly relationship with him. If you think so, let him tell you that what you gave him isn’t enough. Your mother could tell you it wasn’t enough, and you wouldn’t get mad. But with the blind man, you would. You don’t have a friendly attitude toward him; you have a sympathetic attitude.

So I’ve got to figure a way out. One night, I was out of work, hadn’t been out of the house in about four days because I didn’t have any money, and there were about thirteen inches of snow. I was lying on the couch and looked across at Lil. Bitter at the whole world, nobody to pick on but her, I said, “What would you do if from here on in I started referring to you as ‘bitch’?” She jumped out of the chair and said, “I would simply ignore you.”

I fell out of the couch and laughed so hard they had to call a doctor ’cause I was bleeding inside. That was the answer that I wanted in a nightclub. That quick, sophisticated answer, with no bitterness. That way I wouldn’t give the audience time to feel sorry for me. Once I had this, I’m ready.

I went into a very unsophisticated white club on the outskirts of town, in a neighborhood where I’m dealing with the factory worker whose only mark of dignity is to be the foreman over “that n*****,” and can get away from him on the weekend. Then one night it happened. A guy called me a n***** and the audience froze. I wheeled around without batting an eye and said, “Did you hear what that guy just called me? Roy Rogers’s horse ‘Trigger’!” I hit them so quick and so fast that they laughed, because this is what they wanted to believe he had said. Now that I had them locked up completely on my side, I said, “My contract reads that every time I hear that word, I get $50 more a night. So would everybody in the room stand up and yell it?”

Then I got a job in Mishawaka, Indiana, for $10 a night. The white people lined up at eight o’clock to see this thing. On a Saturday night, a group of white girls were sitting over in the lounge chairs far back to my left. One of them yelled out, “You’re handsome.” Every white man in that place froze. The sex angle was thrown right in my face, and they could hate me for it. I looked at the girl and said, “Honey, what nationality are you?” She said, “Hungarian.” I said, “Take another drink and you’ll think you’re Black, and you’ll run up here and kiss me and we’ll both have to leave this town in a hurry.” I got myself and the nightclub owner off the spot. I left there feeling pretty good because I had tested a white audience with the type of things I wanted to use.

*

An entertainer named Irwin Corey refused to work a Sunday night at the Playboy Club. My agent, Freddie Williamson, got me in there for $50. I never will forget it. It was very cold out, and I didn’t know that much about the Loop. I borrowed a quarter carfare from the people downstairs. That just shows you how amazing life is. For the biggest job I ever had in my life, I had to borrow a quarter. For the job that made me, that skyrocketed me to $5,000 a week, it seems like you would have to borrow $1,000, but it was just a quarter separating me from one of the biggest things that would ever happen to me.

I got on the bus, but not knowing the right way, I had to walk about twenty blocks to the Playboy. It was like when I was a kid, there I’d get so cold on my paper route the wind would knock the water out of my eyes. I am almost frozen by the time I get to the door, and when I walked up, they gave me the news: “We’re sorry, but you can’t go on. This room has been sold out to a southern frozen food convention, and we didn’t know it.” I think had I not been so cold and so mad, I probably could have accepted it, but after that walk, I explained to the room manager that nothing short of death itself would keep me from going on.

Working the Playboy Club, I had figured out the solution to this whole problem of cracking the top white nightclubs.

It’s one thing having local yokels, the poor whites of Chicago, heckle you. It’s another thing having the businessman, the man that’s spending top dollar, a man that’s been around. An audience that, when it’s all over, you can’t say, “These are ignorant white folks.”

As I sat there on that stage, I went all the way back to childhood. To the smile Mom had on her face, to the clever way of being so bitter inside but smiling on the outside, when your rent wasn’t paid and you knew they were going to cut you off, when the lights were cut off but you could see in the dark. I went through all of this sitting up there on that stage, and when it was all over, I smiled.

The audience fought me and with their dirty little insulting statements. I would accept it and say something very clever back, to the extent where they broke. And when they broke, it was like the storm was over. They turned around, and they looked, and they listened. What was supposed to be a fifteen-minute show lasted an hour and ten minutes. They didn’t let me off. Every time I tried to get off, they called me back. When I finally walked off the stage, these southerners stood up and clapped. One of them looked at me and said, “You know, if you have the right managers, you’ll die a billionaire.”

Working the Playboy Club, I had figured out the solution to this whole problem of cracking the top white nightclubs. I wasn’t broke nowhere but in my pocket.

__________________________________

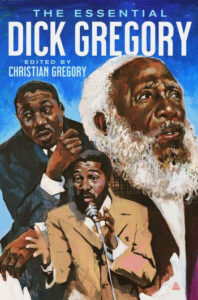

Excerpted from: The Essential Dick Gregory, edited by Christian Gregory. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2022 by The Estate of Richard Claxton Gregory.

Dick Gregory

Richard “Dick” Claxton Gregory was an African American comedian, civil rights activist, and cultural icon who first performed in public in the 1950s. He was on Comedy Central’s list of “100 Greatest Stand-Ups” and was the author of fourteen books, most notably the bestselling classic Nigger: An Autobiography. A hilariously authentic wisecracker and passionate fighter for justice, Gregory is considered one of the most prized comedians of our time. He and his beloved wife, Lil, have ten kids.