How Democratic Senator Mazie K. Hirono Became a Fierce Advocate for Women and Children

Recounting the Path of the First Asian American Woman and the Only Immigrant Serving in the US Senate

The efforts of my family, as well as volunteers and other friends and supporters, carried me to victory in Hawaii’s 12th state house district in 1980. Though I had been involved in democratic politics in my home state since the early 70s, this would be the first time I held public office.

My old friend, David Hagino, the other representative from the 12th district, was enthusiastic about having a partner in the House who could help him turn his big ideas into reality. I didn’t mind his presumption. I had always respected David’s creativity and commitment as a public servant, so it didn’t matter to me whether a bill or policy agenda had originated with him or with me. While I was well aware that David considered me his protégée, I also knew that I had been elected to office just as he had been, which made me every bit his equal. And having served for two years as state senator Anson Chong’s legislative chief before law school, I was no neophyte regarding House procedures.

I was sworn in the following January, becoming one of only ten women in the 51-member state legislature my first year. Though a minority in terms of gender, as an Asian American I was in the majority. The strong Asian American influence in Hawaii politics had begun during what was colloquially known as the Democratic Revolution of 1954, when Hawaii was still a US territory. The territorial election that year had sent an unprecedented number of Democrats to the State House, breaking the decades-long hold of the Republican Party and the Big Five haole-run corporations.

The seeds of this revolution had found fertile soil when Asian Americans like Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga returned to the Islands after fighting for the United States during the Second World War. Seeking to establish themselves in postwar Hawaii, they found the business class closed to them and had turned to politics instead, joining with powerful labor unions to put their preferred candidates in office. Asians in Hawaii quickly coalesced into a dependable voting bloc for the Democratic Party, electing Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, Native Hawaiian, and mixed-race candidates in ever-increasing numbers, and eventually sending both Inouye and Matsunaga, as well as Patsy Mink, to the US Congress in the 1960s.

If race played a minor role in my interactions within the State House, my gender was more of a factor. Aware of how few women there were in the House, I was determined not to allow male colleagues to dismiss me, behave flirtatiously with me, or treat me as anything less than a peer. I soon earned the nickname Ice Queen thanks to the chilly demeanor I adopted to defend against the nonsense that came my way from some of the men.

The Democratic chairman of the powerful Finance Committee, for example, wanted everyone to call him Uncle Tony, but I steadfastly refused. His seat in the tiered House chamber was in the last row, a position from which he could survey everyone else. I sat several rows in front of him, and he sometimes tried to get my attention using what we referred to locally as a “love call.”

“Pssst, pssst,” he would hiss at me from his seat at the back of the chamber.

I assiduously ignored him, much as my mother had once advised that I ignore my high school newswriting adviser when she kept hassling me. Yet the chairman kept using the call. Finally, I’d had enough. I turned in my chair and fixed him with an icy stare, an expression my staff had learned to refer to as “the look.”

“I don’t answer to that,” I said.

“What?” he said, his eyes dancing with mischief. I could see this was all a big joke to him.

“Well, what do you answer to then?”

“Try Mazie,” I said.

He laughed at my audacity. He was a powerful senior member of the House, after all, and I was in my first term. But he never again addressed me by anything other than my name, and we went on to forge a cordial working relationship.

Another way in which men took the women in the State House for granted was in the giving of lei to people who were being honored for their service to the community. In Hawaii, women traditionally present lei to men, and men present lei to women. Since most of the honorees were men, our male colleagues would simply leave a pile of lei on our desks with a list of honorees and expect that when these men entered the chamber, we would jump up happily and present them with the lei. But they never asked us directly. It was this presumption, and the fact that so few women were similarly honored, that made me decide I wasn’t going to participate in the presentation of lei.

And so the first time I saw a male colleague about to leave a lei on my desk, I told him, “I don’t do that.”

He looked at me with surprise. “You’re supposed to give the lei to our honoree,” he responded, assuming I hadn’t understood the procedure.

“I don’t do lei,” I repeated.

He took the lei away, and he must have spread the word, because no lei was ever left on my desk with the idea that I would spring up and give it to the man being honored. Sometime later, David came over to me during a break in session, chuckling about my refusal to present lei.

“Mazie, you can stop now,” he said. “You’re getting a reputation as a hard-ass.”

I only laughed. I did not mention that our male colleagues had now started asking the women to present the lei for them rather than merely dropping the pile on their desks. Point taken, I thought.

*

My approach as a legislator was to focus on the issues that had inspired me to become a public servant in the first place: workers’ rights, women’s concerns, public education, and consumer protections. My goal was to help the most defenseless among us, and for me, these vulnerable ones had faces: the youth of Waimanalo; the residents in that rooming house on Kewalo Street; farm families in Koko Head and maids in Portlock; and children like my own brother Wayne, who might need special teachers and schools. Unfortunately, however, the men in the State House routinely voted down legislation put forth by the women, such as bills designed to protect domestic violence and sexual assault victims. Since women members were in the minority, we needed the support of the men to get such laws enacted.

Some of the other House women and I proposed a Women’s Caucus to help get our bills to the floor. The men tried to dissuade us.

“Why do you want to create your own caucus?” the leaders cajoled.

“We should all be working together.”

But the bills of particular interest to women continued to routinely be held in committee, never coming to the floor for a vote. Refusing to be deterred a second time, the women legislators joined together to form our Women’s Caucus, which exists to this day. Our strategy was bipartisan unity. At the start of each legislative season we would work with advocacy groups to develop a package of bills to benefit women and children, and then hold a press conference to unveil our initiatives. Not only were we a formidable group of women legislators, but also going public with our policy agenda at the outset made it harder for our male colleagues to overlook or vote against our proposals, because now they would appear to be misogynists.

My goal was to help the most defenseless among us, and for me, these vulnerable ones had faces.

Among the first bills I got passed was an amendment to the Hawaii rape law that forced the court to focus on the conduct of the attacker rather than on the response of the victim. Prior to passing the bill, defense lawyers were allowed to ask rape victims questions like “What were you wearing?” and, perhaps most pernicious of all, “Did you resist?”

If rape victims could not prove they had resisted, then the court deemed that to mean consent, even in statutory cases where the victim was 12 or 14 years old. With our amendment, defense lawyers now had to refrain from asking these kinds of questions. They were no longer allowed to revictimize the victims.

I also introduced legislation to provide resources to train prosecutors in the sensitive handling of sexual assault cases, with a goal of promoting greater understanding of the psychological trauma of the victims. Our Women’s Caucus also helped to create a rape victims fund; increase childcare tax credits; pass job security provisions for employees who took unpaid family leave; and provide tax credits to employers who offered childcare. Protecting the rights of women and children and improving the chances that justice would be done in sexual and domestic assault cases would remain enduring commitments for me; 37 years later, I would welcome the women-centered #MeToo movement as a long-overdue drive for gender equity and fairness under the law.

Another top priority of mine was education. I introduced several bills aimed at ensuring that public schools had the resources to reach and secure all the children in their care. An important initiative that I was glad to support was Native Hawaiian language–immersion programs. The Native Hawaiian population had been decimated by diseases carried by the first Europeans to arrive, and they had continued to be disproportionately affected by new diseases brought by waves of immigrants to the Islands. Christian missionaries had also discouraged or outright banned important cultural practices such as the hula. Later, led by descendants of these same missionaries, the provisional government had banned teaching the Hawaiian language.

By the late 1970s, the Native Hawaiians were on the verge of losing their language entirely, and with it a critical part of their culture. The creation of language-immersion schools to teach the Hawaiian language has gone a long way toward restoring their social traditions, centering their history, and recognizing their importance to the state.

My own experience had shown me that language was a cornerstone of cultural identity and must be actively preserved. When I’d first arrived in Hawaii, at the age of seven, I was discouraged by my teachers from using my first language, Japanese, and had lost my ease with speaking it as a result. I hadn’t thought much about this as a child, because as an immigrant, the goal was to assimilate, which meant learning to speak English and using it at virtually all times. To regain familiarity with my first language, I had enrolled in Japanese-language courses in both high school and college. But when in adulthood I traveled to Japan with my mother to visit relatives, though I could understand much of what was said, I could not respond in Japanese with any fluency.

With a pang, I realized that in failing to maintain my first language as a spoken habit, I had allowed a crucial piece of my identity to be stripped away. As a state legislator, I resolved to hold the line in some small way against the same loss of identity for Native Hawaiians. As so often happened for me, it was the faces of the underprivileged teens I’d worked with one summer in Waimanalo—many of them native Hawaiian—that came back to me as I spoke in favor of legislation that would restore Hawaii’s original language to its pride of place within our Islands.

__________________________________

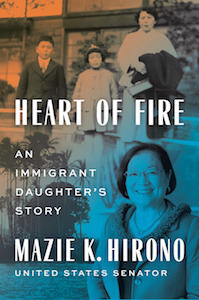

Excerpted from Heart of Fire: An Immigrant Daughter’s Story. Used with the permission of the publisher, Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mazie K. Hirono.

Mazie K. Hirono

Senator Mazie K. Hirono is a graduate of the University of Hawaii, Manoa and the Georgetown University Law Center. She has served in the Hawaii House of Representatives (1981-1994), as Hawaii’s lieutenant governor (1994-2002), and in the U.S. House of Representatives (2006-2013). She became Hawaii’s first female senator in 2013, winning reelection in 2018. Hirono serves on the Committee on the Judiciary, the Committee on Armed Services, and the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, among others.