How Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi Became Superstars On and Off the Field

Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg on the Making of Soccer's Greatest Rivalry

Two of the greatest soccer players who ever lived sat awkwardly in a Swiss opera house wondering why they’d bothered to show up. There was the floppy-haired Lionel Messi in a dark suit that draped over his narrow shoulders. And there was Cristiano Ronaldo with diamond studs in his ears and wearing a tuxedo, even though the event was expressly not black tie. Neither of them wanted to be there. Neither of them was allowed to leave.

The reason they slouched like punished schoolboys was the empty seat between them.

At their first ever FIFA World Player Gala—an annual celebration of dazzling skill, relentless drive, and uncomfortable banter—Messi and Ronaldo had both been voted not quite the best men’s player of 2007. Instead, that honor had gone to a Brazilian playmaker named Ricardo Izecson dos Santos Leite, or Kaká for short, who was now up onstage collecting his trophy. He was older than Messi and Ronaldo, and as far as they were concerned, he was also worse at soccer.

At least two other people in the velvet opera house seats that night agreed.

One was a Portuguese former nightclub promoter named Jorge Mendes, who was remaking himself as a slick-haired soccer agent by moving Iberian and South American players around Europe as casually as he juggled his many cell phones. Putting Ronaldo on that stage was a key piece in his master plan to make his client the richest athlete on the planet.

What no one could predict in Zurich that night was that the guys who finished second and third were about to transform soccer into an individual sport.

The other Jorge in the room was even more outraged. That would be Jorge Messi, father of Lionel, who still spent much of his time in their hometown of Rosario, Argentina. It had been barely seven years since he bundled his sobbing son onto a flight to Spain in the hopes of impressing some coaches at FC Barcelona. Now the former supervisor at a metal factory was an agent too—with one client who happened to share his last name—fumbling his way through the most cut-throat business in sports.

That night, they all learned a vital lesson. Award shows like this one had never counted for much in soccer before. The trophies that mattered were the ones handed out on the field, at the end of a struggle, with everyone wearing shorts, not designer suits. But that was about to change. The game they grew up with had never known an era-defining rivalry between two soloists. What no one could predict in Zurich that night was that the guys who finished second and third were about to transform soccer into an individual sport. Award shows would become their unlikely battlefield—just as soon as Messi and Ronaldo could start winning them.

Still, Messi, Ronaldo, and the Jorges couldn’t get over the fact that this event, with potential long-term effects on transfer fees and sponsorship deals, was run like Sepp Blatter’s personal cocktail party. Long before he was found to be paying himself tens of millions of dollars in illicit bonuses—which is to say, while he was still enjoying those bonuses— the longtime FIFA president concocted the awards ceremony as yet another way to surround himself with soccer legends and supermodels.

And this year, for the first time, the gala was being broadcast live, in its entirety, with Blatter playing his favorite soccer role that wasn’t center forward: center-stage emcee. Next to him was a pair of Swiss TV personalities whose job it was to keep the proceedings moving and repeat Blatter in French, English, and German. But to present the marquee award of the night, the FIFA president needed more heft. He called on none other than the most prolific goalscorer and soccer pitchman of all time, the three-time World Cup winner Pelé. It was the FIFA equivalent of the Grammys trotting out Paul McCartney.

[Ronaldo] had discovered something even more awkward than showing up to this event and losing: showing up to this event and being made to turn his trophy over to Messi.

The organization that Blatter had built up from a small promoter of soccer tournaments into a global monster of marketing and television rights was sitting on roughly half a billion dollars in cash at the time. In its day-to-day operations, FIFA was more like a record label or a medium-sized insurance firm than a sports body. And just like any self-respecting record label, it held a vital stake in manufacturing its own stars.

The problem was that in the mid-2000s the soccer skies were a little dimmer than usual. The four men who had shared every award from 1996 to 2005 were now in their twilight years. Age and weight had caught up to the Real Madrid Galácticos—Zinedine Zidane, Luís Figo, and the Brazilian Ronaldo. The two-time winner Ronaldinho, meanwhile, was barely finding time to play matches for Barcelona between all-night beach parties. Things were so thin at the top of the soccer food chain that in 2006 the distinction for the world’s best, most exciting talent went to Fabio Cannavaro. He was a defender.

Now, it was Kaká’s turn. The clean-cut, middle-class kid from Sao Paulo ran AC Milan’s midfield with an easy grace that belied what a nightmare he was to face. Kaká, a freshly minted European champion, had been the golden boy before Cristiano was the golden boy and long before Leo had finished growing to five-foot-seven.

“Ladies and gentlemen, the crucial moment. I have some practice to open envelopes,” Blatter said, without a hint of irony. “Ladies and gentlemen, the winner of the FIFA World Player 2007, of this gala here in Zurich, is Kakaaaa.”

Kaká got up. Pelé, a man who had shilled for everyone from American Express to Viagra, proudly endorsed his countryman. Messi and Ronaldo stayed benched.

Making matters worse for the sulking pair, they’d been through the same drill two weeks earlier in Paris at the Ballon d’Or, a separate player of the year award that would later be unified with the FIFA prize. So the element of surprise was somewhat dampened. “To be honest, I was expecting it a little bit,” Kaká said. “I won the Champions League and was the competition’s top scorer… That is the key. You have to play in a winning team.”

For an entire era of the game’s history, one man or the other would claim soccer’s top individual award every single year.

Not that Messi and Ronaldo were playing for pub sides. Messi, 20, had broken into the starting lineup at Barcelona under the former Dutch great Frank Rijkaard, who was doing his level best to figure out what position this dribbling Argentine actually belonged in. And Ronaldo, 22, was a bona fide star at Manchester United, where his manager, Alex Ferguson, had spent four years toughening him up to become the most complete attacker in the game.

Messi and Ronaldo were already world-class, with Champions League and Premier League winners’ medals at home. Yet Kaká had captured more votes than both of them combined. As a final indignity to the losers, Blatter invited them up onstage to pose for photographs. Pelé handed each of them a little trophy, smaller than Kaká’s, only to realize that he’d mixed them up.

Somehow he’d handed the second-place prize to Ronaldo and the third-place trophy to Messi. Blatter had to intercede, shuffling between the soccer geniuses to make sure everyone was holding the right hardware. “Second, second for Lionel,” said one of the two other hosts onstage, in the kind of generic European accent that populates world soccer. “Could you change it please?”

For a moment, Ronaldo came as close as possible, for him, to feeling embarrassed. He had discovered something even more awkward than showing up to this event and losing: showing up to this event and being made to turn his trophy over to Messi. They traded second and third places while Ronaldo hoped for the opera house to open up and swallow him whole. When that didn’t happen, he endured one last shot. “You tried, you tried,” one of the hosts said as the crowd giggled. “But you didn’t manage.”

He didn’t manage a smile either. Ronaldo and Messi were forced to stand onstage through the end of the show until an orchestra played them off with “The Impossible Dream” from the musical Man of La Mancha. They hadn’t come to the opera for Broadway numbers. And they certainly hadn’t come to not win.

As it turns out, that wasn’t a problem for long. By the time someone not named Ronaldo or Messi won the award next, it would be 2018, 11 years later. No matter what Kaká said about winning teams, this prize was the ultimate yardstick for individual achievement in the world’s favorite team sport—and the award Messi and Ronaldo cared about most.

This was also the rare arena where they could be compared independently of their teammates or circumstances. Here was a live measure of all-time greatness, Messi or Ronaldo, Ronaldo or Messi. For an entire era of the game’s history, one man or the other would claim soccer’s top individual award every single year—a decade defined by their personal duels, their staggering numbers, and the wreckage they left behind.

___________________________________

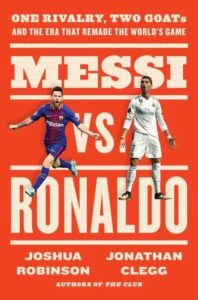

Excerpted from Messi vs. Ronaldo: One Rivalry, Two GOATs, and the Era That Remade the World’s Game by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg, published on November 1 by Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2022 by Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg. Reprinted by permission.

Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg

Joshua Robinson has been the European sports correspondent for the Wall Street Journal for over a decade. In addition to soccer, he has covered everything from the NFL and the Olympic Games to the Tour de France, and the World Chess Championship. Robinson’s work has also appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Sports Illustrated. A native of the South of France, he was raised in London and is a graduate of Columbia University. He is based in Paris.

Jonathan Clegg is a senior editor for the Wall Street Journal. He joined the Journal in 2009 as the paper’s first Europe-based sports reporter and has since written about every major sport, covering the Super Bowl, the College Football Playoff, the World Cup, and the Olympics. He is a graduate of the London School of Economics and lives with his wife and two children in Brooklyn.