How Colorism Impacts Black Women’s Physical and Mental Health

Layal Liverpool on Racist Beauty Standards and the Hidden Harms of Hair Relaxers

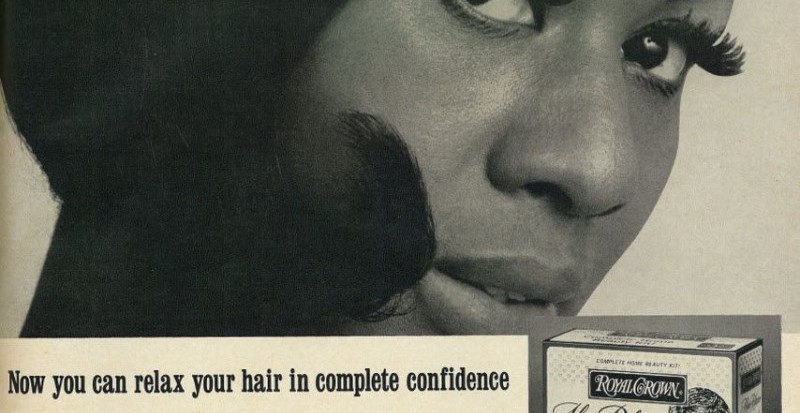

For most of my life I didn’t feel I could wear my hair the way it naturally grows from my head. As a child, I already stood out from the crowd at school because of my brown skin, but the thing that I most remember being bullied about was my hair. My mother tried to protect me: from the age of about five, she started taking me to the hairdresser to get my hair relaxed, meaning chemically straightened. Later, she began buying the products herself and relaxing mine and my younger sister’s hair in our bathroom at home. “I wanted my kids to be accepted, to fit in,” she later explained to me.

Growing up in Lebanon in the 1960s and 70s as the only Black child in her family, and one of only two Black children at her school, my mother faced significant discrimination. She is Lebanese on her father’s side, and Ghanaian on her mother’s side. Her parents divorced when she was a baby, in Ghana, and she eventually ended up in the care of her father’s family in Lebanon. He soon got remarried to a Lebanese woman—my teita (grandma in Arabic)—and together they had five more children. Being the only Black or Mixed child in her lighter-skinned family was tough for my mom. During family outings, people found it difficult to believe she was part of the family.

Her hair was also an issue for people. Her family didn’t know how to take care of textured hair, so they always kept her head closely shaved. She was bullied about her hair at school, further lowering her already low self-esteem. This was all the more reason why she was delighted, as a teenager, when she learned of a product that could make her hair straight.

I think a part of myself was also being washed down the drain, along with those nasty-smelling chemicals.

“I was desperate to fit in,” she told me. “I had no idea what it was and what it involved,” she said, remembering her first hair relaxing appointment. “It was an unpleasant experience.” In those days, she recalled, the hair relaxing products available were very thick pastes that were difficult to spread onto the hair—and they didn’t smell great. The process could also be painful. “I started experiencing this tingling and burning,” my mom said.

Listening to her describe those sensations brought back memories of having my own hair relaxed. I would sit patiently with my scalp on fire because there was this notion that the longer you left the product on your hair, the straighter it would become. Eventually, I would be relieved by the flow of water against my hair and scalp, removing the foul-smelling product and leaving me with what I hoped would be a slightly more acceptable appearance. Looking back, I think a part of myself was also being washed down the drain, along with those nasty-smelling chemicals (and a bunch of money).

“I feel saddened and angry that we were made to feel inferior, because of frizzy hair,” my mom said. Even though she experienced “a few little burns” on her scalp from relaxers on one or two occasions, she thinks the emotional scars from that feeling of inferiority affected her more.

She and I were both wearing our hair naturally as we sat together in her living room, sharing experiences. I stopped relaxing my hair when I was in my early twenties, in the early 2010s; the natural hair movement was taking off at the time, encouraging people like me to embrace our natural Afro-textured hair. My mom and sister soon followed. My mom was in her early fifties when she stopped relaxing her hair. “Seeing you and your sister embracing your natural hair really impacted me,” she said, tears in her eyes. “It makes me very proud.”

I don’t judge my mom for choosing to relax my hair when I was a child, nor myself for continuing to do it as a teenager and young adult.

There are plenty of reasons why millions of people with textured or Afro hair globally use products to chemically straighten it. But I think a lot of those reasons are related to racism—or, more specifically, colorism.

The author and activist Alice Walker is often credited as being the first person to use the word colorism, which she defined in her 1983 book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens as “prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color.” Colorism is usually associated with preference for lighter skin tones and prejudice against darker ones. In practice, colorism often also encompasses featurism—a less frequently used term that refers to similar prejudice based on commonly racialized features, such as nose or eye shape and hair texture. At its root, colorism is a form of racism—but while racism separates people into racial and ethnic groups, colorism typically separates people within those groups. Like racism, colorism manifests both at a systemic and an interpersonal level, and causes harm to mental well-being as well as to physical health.

My mom told me that when she worked as a pharmacist in London in the 1980s and ’90s, even though she was part of a diverse team, she didn’t feel that natural hairstyles would be considered acceptable in her workplace. “There was nobody who was going with natural hair,” she said. A few decades later, when I was living in London myself, I was preparing to travel to Oxford for a PhD interview when a Black friend recommended that I should straighten my hair before leaving. “You can’t show up with an Afro,” she said. “It isn’t professional.” I am proud to say I showed up with my Afro anyway and I was accepted into the PhD program but, unfortunately, many people aren’t so lucky.

In 2016, about a year after that PhD interview, Google’s image search feature came under criticism after a user tweeted screenshots revealing that a search for “unprofessional hairstyles for work” retrieved mainly images of Black women with natural hairstyles. Typing “professional hairstyles for work” into the search bar, on the other hand, yielded mainly photographs of White women with straight hair. In the US, the last few decades have seen numerous court cases filed by Black employees alleging workplace hair discrimination and, as of 2022, at least eighteen US states have felt the need to pass legislation known as the CROWN Act to explicitly make hair discrimination illegal.

If discrimination at work and at school wasn’t enough to persuade someone to try chemical straightening, worrying about their safety might. The first time I remember being called the N-word in a threatening manner, by a group of guys outside a nightclub in the Netherlands, they used my hair to target me. I hadn’t touched up my roots for a while, so even though most of my hair was still relaxed, it looked more textured than usual. “N***** with the Afro!” I remember them shouting. I was a teenager at the time and I felt afraid. I had lost track of my friends, so I was on my own. I rushed home as fast as I could, my heart racing.

The pressure for Black women, in particular, to solve the problem of hair discrimination by using products like relaxers comes with its own very specific set of potential health risks. Chemical burns are an example. “Some women do actually suffer third-degree burns, chemical burns,” said Kimberly Bertrand, an epidemiologist at Boston University School of Medicine in Massachusetts whom I spoke with a few weeks before my conversation with my mother.

Bertrand and her colleagues published a study in 2021 examining data on hair relaxer use and breast cancer incidence among a group of more than fifty thousand Black women in the US. She emphasized that the main takeaway from that study was that moderate use of hair relaxers wasn’t associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. “Our findings, I would say, were really quite reassuring,” said Bertrand. “For most women in our study, there was no evidence of a link between use of these relaxers and future breast cancer.”

However, Bertrand and her colleagues did notice a slightly concerning pattern among a subset of the women in the study who reported using hair relaxers containing a chemical known as lye. They found that the women who reported using lye-based relaxers most frequently and over the longest periods of time—more than seven times a year for a period of more than fifteen years—were 30 percent more likely to develop breast cancer, compared with those who reported lighter use of these products.

The data Bertrand and her colleagues analyzed was from the Black Women’s Health Study, which began tracking the health of fifty-nine thousand self-identified Black women in the US in 1995, with the hope of identifying factors contributing to racial disparities in health. The enrolled women, who were aged between twenty-one and sixty-nine at the time the study started, regularly complete surveys and share health data to provide a resource for researchers to identify potential associations between various environmental factors and health outcomes.

Bertrand is particularly interested in breast cancer.

“Black women are 40 percent more likely to die from their breast cancer than White women,” she noted. “In the US, you can imagine that there are lots of factors that contribute to that higher mortality. Much of it is, I would say, racism,” she said.

We both wondered what we might have done differently if we had been more aware of the potential health risks associated with hair relaxers.

“Relaxers are heavily marketed to Black women,” said Bertrand. She explained that after coming across earlier research highlighting a potential link between exposure to some of these products and breast cancer risk, she had decided to investigate further. “Chemical hair relaxers or straighteners, as we call them, we know they contain many thousands of chemicals,” she told me. “And we know they contain chemicals that are known to be toxic, especially these toxic chemicals called endocrine disruptors.”

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that can interfere with signaling by hormones, such as the sex hormone estrogen, which plays a key role in many breast cancers. These chemicals may have profound effects on our bodies. A 2011 study led by Tamarra James-Todd, an epidemiologist now at Harvard University, found that African American children were more likely to use hair products and to start menstruating at younger ages compared to children belonging to other racial and ethnic groups in the US.

A more recent study by James-Todd and colleagues showed that several hair products commonly used by Black women exhibit hormonal activity in laboratory tests, suggesting that they could potentially contribute to reproductive and metabolic health disparities. And although Bertrand’s research suggests that moderate use of hair relaxers in general doesn’t increase breast cancer risk, she believes the observation of greater risk among heavy users of lye-based products in particular warrants further investigation. “I don’t know if this is why these women got cancer. But it does make you think, what can we do as a society to make these products safer, or to counsel women about the risks in their own daily lives?” she said.

When my mother and I were swapping stories about our experiences with hair relaxers a few weeks later, I thought back to my discussion with Bertrand. At the time when my mom started relaxing her hair, the range of products on the market was quite limited. She remembers all the products available to her being lye-based ones. By the time she started taking my sister and I to have our hair relaxed as children, the range of available products had expanded, and many were non-lye relaxers.

In fact, my mom said that the products that were used on my and my sister’s hair were specifically marketed as being for children. I asked her if she had ever been concerned about the potential health risks associated with any of the ingredients in these types of products, particularly the lye-based ones that she had used on her own hair for many years. “No,” she answered. “It never occurred to me about the chemicals in the products, but I was concerned about the burn. I thought, this can’t be good for your scalp to have repeated burns,” she added, though I couldn’t help but worry about the potential harm done beyond her scalp.

Bertrand suspects that lye, which is particularly harsh, may damage the scalp in such a way that it makes it easier for other chemicals in the hair relaxer to then penetrate the skin and potentially cause further harm. “Our skin is a big component of our immune system. The purpose of our skin is to serve as a physical barrier to the outside world,” she said. “If you’re getting scalp burn on your head, and creating wounds, that’s a mechanism of entry for the hair straightener to enter your bloodstream, and these other chemicals, the known endocrine disruptors or potentially other toxic chemicals, to get into your system,” Bertrand explained.

Even in the absence of a visible burn or wound, the lye could still be causing microtears to the skin, she pointed out. An increased penetration of endocrine disrupting chemicals through the scalp and into the bloodstream following use of lye-based relaxers could potentially explain why the heavy users of these products in Bertrand’s study had an increased risk of breast cancer.

Bertrand thinks the contents of hair relaxers should be more tightly regulated, for instance by the FDA. “I consider this an issue of environmental justice,” she told me. Indeed, the vast majority of people who use hair relaxers around the world are Black. My mother agrees—she suspects that the fact that the main users of hair relaxers are Black women may have something to do with the limited amount of research and regulation in this area, particularly at the time when these products first became available on the market.

Sitting together in the living room, we both wondered what we might have done differently if we had been more aware of the potential health risks associated with hair relaxers. Would my mom still have opted to chemically straighten her hair all those years? We agreed that she might have, because the pressure to feel accepted by society was that strong. “I think if I was accepted and liked for who I am, it would never have occurred to me to make any changes about how I look,” she said. “I think the major factor in me having to do things like that is the fact that I was discriminated against and there was racism, and I wasn’t accepted as I am.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Systemic: How Racism is Making Us Sick by Layal Liverpool. Published by Astra House. Copyright © Layal Liverpool 2024. All rights reserved.

Layal Liverpool

Layal Liverpool is a science journalist with expertise in biomedical science, particularly virology and immunology. Her PhD research at Oxford focused on investigating how invading viruses are detected by the body’s immune system. She writes news, features and opinion articles about the latest scientific research, from technology and space, to health and the environment. Her writing has appeared in Nature, New Scientist, Wired and the Guardian. She is a former journalist for Nature.