How Colonization and Christianity Challenged Indigenous Maya Spirituality—and Failed

Emil’ Keme on the Popol Wuj, K’iche’ Authors, and Poetry as Resistance

The Popol Wuj (also written as Popol Vuh and Pop Wuj), the “Book of the Community,” was written between 1554 and 1558 and is one of the most important K’iche’ Maya books in the history of the Mayab’ region—present day Southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and northern El Salvador. Some scholars believe that the authors of the text were three K’iche’ Maya young men whose ages ranged between 14 and 18 years. Two of the writers are thought to be Don Juan de Rojas and Don Juan Cortés, descendants of the kings of the city of Q’umarkaj (The Big House), Oxib-Quej (Three Deer), and Belejeb-Tzi (Nine Dog), who had been burned alive by the Spanish invader Pedro de Alvarado on his arrival to their city.

The other young man, it has been suggested, was Cristóbal Velasco, a Nim choq’oj or “Master of the Word” of this period, who lived in the same K’iche’ city. His work was to recite historical accounts, stories, and the names of old warriors during festivities and important events. Despite the uncertainty about the authors of the text, most scholars agree that the book was authored by at least three writers.

During the colonization of Q’umarkaj in March 1524, the K’iche’ people witnessed the destruction of their temples and historical records, the torture and death of their leaders, sexual violence against women, and the beginning of enslavement of yet another Maya Nation; Alvarado, with the help of thousands of Indigenous allies, had already conquered other sectors of the K’iche’ Maya kingdom in what is today Quetzaltenango. The Spanish colonial onslaught in Q’umarkaj included the imposition of Christianity on people who were being instructed as ajtz’ib’ ajk’ot (scribes, or framers of the word) and political leaders. Young Indigenous literate youths like the writers of the Popol Wuj were targeted because they had knowledge about their people’s history, the calendar, culture and spiritual values.

The Spanish priests who accompanied Pedro de Alvarado during the conquest of the Mexica or Aztec Empire had learned important lessons. “Peaceful” efforts to impose Christianity through dialogues with Mexica leaders, priests, and wise elders had failed, because they persistently defended their Indigenous spiritual values. In response to their “stubbornness,” the Spanish tortured and later executed them when they questioned the Christian faith. It was thus concluded that it was better to evangelize and educate the children and young Indigenous people by forcibly separating them from their families and imposing on them new memories and knowledges.

Initially, Indigenous children were sent to Spain to obtain an education, after which they were expected to come back to their places of origin and be the ones to spread the new Western knowledge to their peoples. However, most of them died on their journey to the peninsula. Therefore, the Spanish changed their strategy: instead of sending Indigenous children to Spain, they separated them from their parents and kept them locked up so they forget “idolatries” and received education in the new churches established in the recently colonized territories.

Knowing of the important moral, spiritual, and political authority represented by the K’iche’ authors of the Popol Wuj in the city of Q’umarkaj, the Spanish priests kidnapped and locked them up in churches to start the processes of evangelization and the imposition of Spanish values. They introduced the Christian Bible as the new epistemological referent regarding the “true origins” of humanity and the universe; the priests taught the young men to speak, read, and write in kaxlan tzij (Castilian Spanish) and to use the Latin alphabet instead of the ancestral Maya pictographic and hieroglyphic writing system.

However, in their efforts to make these Indigenous framers of the word ignore their excessive idolatries, the Spanish priests underestimated the young men they sought to evangelize. Naively, the European invaders believed that these Indigenous scribes would suddenly set aside their ancestral spiritual beliefs to openly embrace and adopt Christianity and what Spain offered them. On the contrary, the contents of the Popol Wuj reveal the K’iche’ authors’ sagacity and creativity in their struggle to defend the memories, knowledge, and values of their people tenaciously.

What rhetorical exchanges occurred between the K’iche’ authors and their Christian teachers? What ideas and reflections did they develop when they heard the bishops’ teachings? How much punishment did they endure when challenging the “new” knowledge? What complicit gazes and silences did they patiently exchange in the rooms where they were being instructed about Christianity? What discussions did they hold in whispers about the new concepts and the stories coming from the European peninsula? What exchanges might have occurred among them in solitary rooms or in the darkness of caves in the middle of the night? What patience might they have had to absorb the “new” knowledge, perhaps biting their tongues, knowing that their word did not have an audience under the new colonial reality? In what spaces did they reflect on the strategies they would use to inscribe their millenarian legacy in the “new” books written in the Latin alphabet?

We will never know the exact answer to these questions, nor will we know the dynamics and cultural exchanges between the K’iche’ young men and the Spanish priests while they received instruction in Western knowledge. Nevertheless, despite the full context of colonial violence they were exposed to and the immense and traumatic ideological pressure they were surely subjected to during the height of the Inquisition, as well as their experiencing constant punishment, aggressions, and persecution, these K’iche’ Maya authors found the courage to challenge the colonizers by dignifying the spiritual Maya seeds that their parents and grandparents had planted in their minds and hearts. They soon became aware of the great usefulness of the Latin alphabet in affirming the K’iche’ language and their native histories. They employed it subversively to rewrite history as their first discursive exercise to recover lost political authority, challenging the religious knowledge coming from Europe.

The authors of the Popol Wuj proceeded to present a Maya worldview where humanity and the universe are the result not of the actions of a single god, but of a divine council that gathers to create the world and the humanity who will inhabit it. The council members learn from their mistakes. First, they create the seas, the earth, and the forests and then the animals. They then proceed to create humans out of mud, but these creatures are later destroyed when the gods send rain to earth. After this misstep, the divine council frames humans out of wood; however, they are destroyed when they do not express their gratitude for their creation to the gods. They consequently are turned into monkeys. In a final attempt, the gods create the men of maize, the human creation who now inhabits the world.

They employed it subversively to rewrite history as their first discursive exercise to recover lost political authority.

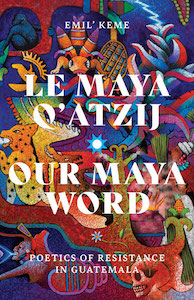

I begin Le Maya Q’atzij / Our Maya Word: Poetics of Resistance and Emancipation from Iximulew/Guatemala by invoking the story of the Popol Wuj and its authors, because hundreds of years after the book was written, the experience of Maya writers resisting colonialism in the modern period is incredibly similar. The Maya people in Iximulew (land of corn, the ancestral Maya name of what is today Guatemala) have recently survived a new colonial assault orchestrated by the Guatemalan nation-state in complicity with the US government. Indeed, in June 1954, four years after the country saw its first democratic regime with the popular election of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, a group of Guatemalan ex-soldiers led by General Carlos Castillo Armas, supported by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), engineered a coup d’état because the actions of the democratic government were harming the economic interests of the United Fruit Company (UFCO).

With the establishment of the Castillo Armas dictatorship, its counterrevolutionary actions included repeal of agrarian reform and the democratic constitution that had been created in 1945: the peasants were forced to return their newly acquired land, which the government then granted to the landowners and the UFCO. The Guatemala Workers’ Party (PGT)—the communist political party in the country—became illegal, and the activities of the workers’ union were forbidden. Social programs that favored Indigenous peasants and the working class were also suspended. Congress was dissolved, and the military government began a hostile relationship with the University of San Carlos, imposing censorship and the “anticommunist” persecution of professors, university students, and leftist intellectuals who criticized the new military government.

These repressive measures and the growing role of the United States in Guatemalan politics soon provoked social discontent, which led to a rebellion in 1960 by a group of army officers who declared war against the nation-state and US imperialism. That armed conflict would last for nearly 36 years. During this period, the Guatemalan state implemented repressive military strategies that were justified by its quest to eliminate the “communist” opposition. Toward the end of the 1970s, such measures became state terrorism and included military attacks aimed at the physical elimination of Maya communities in the rural areas of the country. The Guatemalan Army literally erased more than 600 Indigenous communities.

After the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 and the approval of neoliberal economic programs like the Central American and Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), it became clear that such counterinsurgent tactics had ulterior motives: it is in these Maya ancestral territories where today many transnational companies operate, extracting and exploiting Guatemala’s natural resources. The end results of the internal armed conflict, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established in 1994, were the forcible displacement of 1.5 million Indigenous people from their native territories, the disappearance of more than 40,000, and the assassination of more than 200,000 individuals. Official reports conclude that the majority of these killings constituted “acts of genocide” against the Maya peoples.

This is the historical context that serves as a social referent to analyze the decolonizing efforts of a contemporary Maya intelligentsia who, like the authors of the Popol Wuj, employ the poetic word as an agent of resistance, change, and emancipation. As in the past, theirs is an effort to validate and dignify our ancestral origins as well as our diverse Maya identities and experiences in a present marked by a new colonial violence, now wielded under the banner of neoliberal globalization.

This book offers a critical analysis of the literature written by ten contemporary Maya writers who represent five Maya linguistic communities—K’iche’, Kaqchikel, Q’eq’chi’, Q’anjob’al, and Pop’ti; it explores how these authors and their respective literary works, through the appropriation of the literary register, develop and negotiate their cultural identities and Indigenous rights.

__________________________________

Adapted with permission from Le Maya Q’atzij/Our Maya Word: Poetics of Resistance in Guatemala by Emil’ Keme. Published by the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright © 2021 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota.

Emil’ Keme

Emil’ Keme (a.k.a., Emilio del Valle Escalante) is an Indigenous K’iche’ Maya scholar and associate professor of Spanish at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He is author of Maya Nationalisms and Postcolonial Challenges in Guatemala. In 2020, he was awarded Cuba’s Casa de las Américas literary criticism prize for the Spanish version of Le Maya Q’atzij / Our Maya Word.