How Colonial Powers Fought for Economic Dominance in North America

Hampton Sides on Britain’s Generations-Long Search for the Northwest Passage

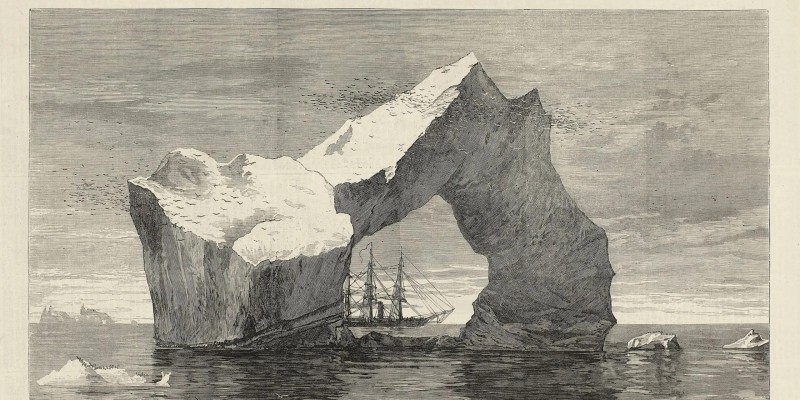

The Northwest Passage: For nearly three hundred years, it had been the grail, the phantom, the will o’ the wisp. Many European nations had yearned to find it, but for the British, it had become an obsession. Over the centuries, the search for it had led to such an unfortunate expenditure of blood and treasure, with so many gothic narratives of frostbite, scurvy, mutiny, starvation, and, in some cases, possible cannibalism.

Each new expedition would start out with optimism, but, often as not, within months the poor explorers would be lost in the wilderness, eating shoe leather or dying of lead poisoning. It had become one of the grim motifs of the empire, with so many lurid dispatches from what amounted to a low-grade war on water, weather, and geography.

By now, a circular argument was at play: The more British citizens who suffered and died in their search for the mystical passageway, the more vital it became to find the damn thing, for otherwise, all those sufferings and deaths had only been a terrible waste.

Each generation had to apply its own inventions and resources and ideas, throwing everything they had at the same old trans-continental problem.

And then there were the memories of those explorers themselves. So many stalwart names had passed down through the ages—Frobisher, Davis, Baffin, Hudson, among others, supremely confident men who had tried so hard to find the way through. The English had to honor them. Painfully, determinedly, these argonauts had wormed their way into North America’s high latitudes, only to find dead ends, tangled landscapes, fantasies and false leads. Why wouldn’t the ice melt faster in summertime? Why did their compasses behave so erratically? Why wouldn’t the land offer more clues?

*

Commerce, of course, was the main impetus behind the quest—the benefits for English trade were potentially enormous. A northwest passage, advocates claimed, would render obsolete the dangerous and time-consuming journey around the bottom of Africa or South America, cutting the long trip in half, they said, reducing a one-year voyage to China down to six months.

There were broader geopolitical reasons, as well. A northwest passage would allow the British to avoid the Spanish, who controlled the waters and ports of South America and absurdly claimed, with a decree of Vatican support, that the entire Pacific Ocean was their exclusive property. A Northwest Passage would be a short-cut, a bypass—a way of triumphing over the Spanish without having to fight them, or even encounter them at all.

Then, too, it would be a way of outmaneuvering the French, something the English were always up for. Throughout the seventeenth century, French explorers such as Champlain, Marquette, Jolliet, and La Salle, had pieced together the enormous puzzle of the Great Lakes and many of the continent’s interior rivers, while also trying to find their own version of a passage to the Pacific.

In these bold and desperate feats of exploration, they pushed ever westward, ever southward, only to reach the inevitable cul-de-sacs. But they had enjoyed other successes. By the end of the 1600s, the French had established an enormous empire in North America that had tapped the continent’s riches—principally, its hides, furs, and fish. New France extended in a crescent from the St. Lawrence Seaway, across the Great Lakes, and far down the Mississippi River.

The Seven Years War changed everything, however. The 1763 treaty ending the war forced France to cede much of Canada, leaving the English as the dominant European power in North America. But the French were still keenly interested in the interior of the continent, and they had not given up on exploration. In 1775, English spies in Paris gleaned rumors that the French were planning their own search for the Northwest Passage over Canada, an expedition to be led by Antoine de Bougainville, France’s greatest explorer-scientist, and in a sense, Cook’s direct rival. This intelligence, though it proved false, was an additional goad that may have helped solidify Cook’s third voyage. England and France, although under more or less amicable terms by treaty, were still locked in mortal competition. Like wounded animals not quite done with the fight, they watched over each other’s every move.

But a British discovery of a convenient passage over the top of Canada would positively unnerve the French. How would they respond? It would be, for the English, an achievement of such prestige and glory that it would serve as a parting insult, the final spit in the eye, to punctuate the end of the Seven Years War.

*

The British obsession to find the Northwest Passage seemed to rise and fall on a thirty-year cycle, as though every generation of Englishmen had to rediscover for themselves the magnificent puzzle and its irresistible allure. It was a quest pursued by “geographical romantics,” wrote Cook biographer J.C. Beaglehole, “an illusion just as sedulously nurtured as that of the great southern continent.” Each generation had to apply its own inventions and resources and ideas, throwing everything they had at the same old trans-continental problem. Maybe this time, with what we know now, with all that we’ve learned, it won’t be so hard.

Luckily, the country’s brightest minds had been hard at work on theoretical aspects of the problem of the ice. Foremost among them was a gentleman thinker named Daines Barrington, a lawyer, antiquarian, and naturalist, and a council member of the Royal Society who was also close to Lord Sandwich. It was Viscount Barrington, in fact, who had first proposed a voyage to hunt for the passage from the Pacific side of North America. In a direct sense, he was the conceptual architect of Cook’s third expedition. If Sandwich was its hard-nosed, practical sponsor, Barrington was its intellectual progenitor.

The eccentric Barrington was a lifelong bachelor with a mousy countenance and a small, knobbed chin. He had studied at Oxford and loved to dive deep into odd nooks of natural science and history. Among other pet projects, Barrington had authored an exhaustive history of early English law going back to the Magna Carta; he’d studied the life cycles of trout in Wales; investigated the card-playing customs of ancient societies; and written about child geniuses (this interest was sparked by his having interviewed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart when the musician visited London as a nine-year-old prodigy).

But the topic that most intensely interested Daines Barrington was the Arctic. He had written numerous tracts on the subject, some of which he read before the Royal Society, and others which he compiled into a curious little volume entitled The Possibility of Approaching the North Pole Asserted.

Among his many dubious theories, Barrington maintained that there was no ice at the North Pole because seawater cannot freeze. Ice in the High North, Barrington contended, was solely the product of frigid rivers and streams emptying into the sea. Collars of freshwater ice thus might form and adhere close to Arctic coastlines, but farther out from shore, the deep ocean was reliably ice-free. “In the seas near the Pole,” Barrington wrote, “it is very probable there is little or no ice, for that is commonly formed in bays and rivers during winter.”

*

To buttress his odd hypotheses, Barrington had interviewed Arctic whaling ship captains, some English but many of them Dutch, who shared beguiling anecdotes that were also probably apocryphal. In reading the accounts Barrington so earnestly assembled, one gets the distinct impression that many of his interviewees had a good time pulling his leg.

There was, for example, a Dutch captain named Goulden, who made the incredible claim that a few years earlier he had sailed within one degree of the North Pole. Goulden and his crew “did not meet with any ice,” Barrington reported, and they had enjoyed shirt-sleeve weather the whole way. It was as hot, said Barrington, “as in the summer at Amsterdam.”

Whatever dangers the voyage might entail, it must be pursued for the greater glory of England.

The story had to be true, he noted as an aside, for people from Holland “are not commonly jokers.”

What all of these anecdotes meant, in Barrington’s mind, was that prior attempts to find a northwest passage had failed principally because the captains had looked for routes too close to land. If they had ventured much farther to the north, and much further out into open seas, they would have sailed unhindered by ice.

In the early 1770s, fired by his optimistic theories about ice formation, Barrington successfully lobbied for a new expedition to hunt for the northwest passage. Command of the voyage was assigned to a friend of his named Constantine Phipps. In the summer of 1773, Captain Phipps ventured to Norway’s Svalbard Island in hopes of sailing up and over the pole and all the way to China. But just beyond the 80th parallel, Phipps was thwarted by a solid wall of ice. After a dicey retreat though treacherous floes, the explorer returned home, lucky to be alive.

Barrington was in no way dismayed by the expedition’s alarming experience. He offered the facile explanation that perhaps Phipps had visited the Arctic pack at a bad time, during a bad year. The ice, he admitted, sometimes had a habit of piling up in one random place or another—but that was merely a temporary “assemblage,” he asserted, and in no way a “perpetual barrier.”

In spite of the nearly disastrous expedition led by Phipps, Barrington managed to convince his friend Lord Sandwich that another voyage to find the passage must be mounted, with one of Britain’s best commanders running the operation. Someone of James Cook’s capabilities, he believed, someone as reliable and methodical and persistent as Cook, could make a success of it.

It was Barrington, also, who proposed the Pacific as the best angle of attack. He was aware of several Russian-backed explorations to Alaska—one of them led by the Danish explorer, Vitus Bering, and another led by Russian fur interests. These voyages had produced maps which had recently been published in London, and one map in particular, known as the Stählin chart, showed a very wide strait separating Alaska from the North American continent, a substantial waterway that would seem to allow a navigator to pursue an unobstructed northeastward course, up and over Canada, directly toward the Atlantic Ocean.

Barrington seemed to have no inkling that these maps were fantastically inaccurate. The large, enticing strait shown on the Stählin chart had to be ice-free. He was so confident of this that he did not think the hull of the Resolution needed any reinforcement. Why would the ship need strengthening, when Cook wasn’t going to encounter serious icepack at all?

There was another seemingly crucial matter that curiously never arose in Barrington’s considerations: Even if the Stählin chart was correct and there was a wide strait that could lead Cook from Alaska over Canada toward the Atlantic, what would happen when his ship reached the other side of the continent? Generations of English explorers had become hopelessly lost in those eastern labyrinths, and often their ships had been squeezed and throttled by the ice. Why was Barrington so optimistic that the same calamities wouldn’t befall Cook’s Resolution as it approached, from a westerly direction, the same pinched puzzles of geography? In Barrington’s writings, the question didn’t come up.

Ultimately, though, Barrington appealed to Lord Sandwich on patriotic grounds. Whatever dangers the voyage might entail, it must be pursued for the greater glory of England. “There is unquestionably no country in Europe,” he wrote, “so well situated for such an enterprise as this.” Barrington hoped his arguments would serve as “cogent reasons for wishing that a project which has dwelt in the mouths and memories of some from the time of Henry the Eighth should be revived, and at length, for the benefit of his subjects, carried into effect under the auspices of George the Third.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook by Hampton Sides. Copyright © 2024 by Hampton Sides. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Hampton Sides

Hampton Sides is an award-winning editor of Outside and the author of the bestselling histories Hellhound on his Trial, Blood and Thunder and Ghost Soldiers. He lives in New Mexico with his wife, Anne, and their three sons.